There is confusion amongst some (many) that somehow the Church of England’s 1662 Book of Common Prayer is normative for Anglicans throughout the world. It is not.

There is confusion amongst some (many) that somehow the Church of England’s 1662 Book of Common Prayer is normative for Anglicans throughout the world. It is not.

[Some of this confusion may be apparent in the Jerusalem Declaration of GAFCON meeting recently].

I would need some convincing that Thomas Cranmer would have agreed with the 1662 revision as it seems to me that it sets in stone some confusion after the disjuncture of the Commonwealth period.

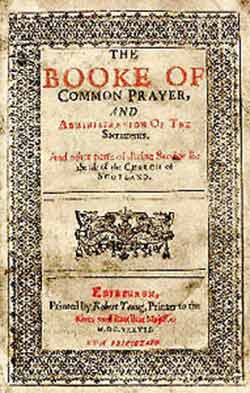

King Charles had the Scottish bishops and Archbishop Laud produce a Book of Common Prayer for Scotland (1637). This was a revision of BCP 1604/1559/1552. The revisions were often minor. It was this book, not 1662 (obviously!) which Samuel Seabury returned with to America, having been made bishop in 1784 in Scotland. You can find the text of the 1637 Scottish BCP here.

Here is the 1764 revised Scottish Communion Office.

This is nearly identical to Bishop Samuel Seabury’s Communion Office that he used as Bishop of Connecticut.

The 1637 Scottish BCP avoided some of the more obvious 1662 confusions. One of the more significant differences is that it had a proper Eucharistic Prayer:

The Presbyter shall proceed, saying,

Lift up your hearts.

Answer.

We lift them up unto the Lord.

Presbyter.

Let us give thanks unto our Lord God.

Answer.

It is meet and right so to do.

Presbyter.

It is very meet, right, and our bounden duty, that we should at all times, and in all places, give thanks unto thee; O Lord, holy Father, Almighty, everlasting God.

Here shall follow the proper Preface, according to the time, if there be any especially appointed; or else immediately shall follow:

THEREFORE with Angels and Archangels, and with all the company of heaven, we laud and magnify thy glorious Name; evermore praising thee, and saying, Holy, holy, holy, Lord God of hosts, heaven and earth are full of thy glory; Glory be to thee, O Lord, most high.

Then the Presbyter standing up, shall say the Prayer of consecration, as followeth, but then during the time of consecration, he shall stand at such a part of the holy Table, where he may with the more ease and decency use both his hands.

ALMIGHTY GOD, our heavenly Father, which of thy tender mercy didst give thy only Son Jesus Christ to suffer death upon the Cross for our redemption, who made there (by his one oblation of himself once offered) a full, perfect, and sufficient sacrifice, oblation, and satisfaction for the sins of the whole world, and did institute, and in his holy gospel command us to continue a perpetual memory of that his precious death and sacrifice, until his coming again; Hear us, O merciful Father, we most humbly beseech thee; and of thy almighty goodness vouchsafe so to bless and sanctify with thy word and holy Spirit these thy gifts and creatures of bread and wine, that they may be unto us the body and blood of thy most dearly beloved Son; so that we receiving them according to thy Son our Saviour Jesus Christ’s holy institution, in remembrance of his death and passion, may be partakers of the same his most blessed body and blood:

Who in the night that he was betrayed, took bread, and

when he had given thanks, he brake it, and gave it to his

disciples, saying, Take, eat, this is my body, which

is given for you; do this in remembrance of me.

At these words (took bread) the

Presbyter that officiates is to

take the Paten in his hand.

Likewise after supper he took the cup, and when he had

given thanks, he gave it to them, saying, Drink ye all

of this, for this is my blood of the new testament, which

is shed for you, and for many, for the remission of sins:

do this as oft as ye shall drink it in remembrance of me.

At these words (took the cup) he is

to take the chalice in his hand,

and lay his hand upon so much,

be it in the chalice or flagons,

as he intends to consecrate.

Immediately after shall be said this memorial or prayer of oblation, as followeth.

WHEREFORE, O Lord and heavenly Father, according to the institution of thy dearly beloved Son our Saviour Jesu Christ, we thy humble servants do celebrate and make here before thine divine Majesty, with these thy holy gifts, the memorial which thy Son hath willed us to make, having in remembrance his blessed passion, mighty resurrection, and glorious ascension, rendering unto thee most hearty thanks for the innumerable benefits procured unto us by the same. And we entirely desire thy Fatherly goodness, mercifully to accept this our sacrifice of praise and thanksgiving, most humbly beseeching thee to grant, that by the merits and death of thy Son Jesus Christ, and through faith in his Blood, we (and all thy whole Church) may obtain remission of our sins, and all other benefits of his passion. And here we offer and present unto thee, O Lord, ourselves, our souls and bodies, to be a reasonable, holy, and lively sacrifice unto thee, humbly beseeching thee, that whosoever shall be partakers of this holy Communion, may worthily receive the most precious body and blood of thy Son Jesus Christ, and be fulfilled with thy grace and heavenly benediction, and made one body with him, that he may dwell in them, and they in him. And although we be unworthy, through our manifold sins, to offer unto thee any sacrifice: yet we beseech thee to accept this our bounden duty and service, not weighing our merits, but pardoning our offences, through Jesus Christ our Lord; by whom, and with whom, in the unity of the Holy Ghost, all honour and glory be unto thee, O Father Almighty, world without end. Amen.

One major historical/factual error here. Seabury was consecrated in 1784 – he did not take the 1637 book with him but Bishop Rattray’s 1764 revision of the Communion office. For ordinary Sunday’s, the normal service in the Scottish Church at that time was generally a service of the Word, virtually indistinguishable from the worship of their Presbyterian neighbours with the addition of the Lord’s Prayer said collectively, the doxology and (at baptism) the Apostle’s Creed. 1662 Mattins was the peculiar preserve of the Qualified Chapels.See http://www.episcopalhistory.org/episcopalian—the-enduring-appeal by Gerald Stranraer-Mull or “Studies in the History of Worship in Scotland” Forrester and Murray (eds) T&T Clark, Edinburgh 1984. 1764 (the source of both the American and South African liturgical tradition) was significantly different to 1637, not least because of its use of the Double epiclesis and its adoption of the Eastern positioning thereof in contrast to 1637’s following the 1549 Eucharistic prayer.

Thanks for this clarification, John, if it was unclear. I thought I was making the point in my fifth paragraph of my post that 1764 stood in the Scottish 1637 tradition, rather than in the English 1662 tradition. I stand by the primary point I am making: 1662 BCP is not normative for Anglicans throughout the world.

Blessings.

I disagree: the 1662 Prayer Book is the closest that Anglicans have to a shared liturgical text. I’m not sure that I would take that to mean that it is normative — implying that it should have a regulating role on current and future liturgy — but it is otherwise the closest we have to a normative liturgical text.

Each of the English revisions of the Prayer Book demonstrate the mold of their historical context. For instance, Martin Bucer’s observations on the 1549 book were taken up in the 1552 revision.

The 1637 revision, for all the Scottish label, stands quite fully in the English process of revision, introduced by James Wedderburn. It was an experiment, and an experiment that paved the way for the move from the 1604 revision to that of 1662. The experimental book’s fate in Scotland was not a good one, and its unmediated impact was slight. Normative it was not.

Samuel Seabury’s Communion Office was based on the Scottish Episcopalian ‘wee bookie’ of 1764. Even Seabury’s influence in the States was not so great, seeing that when English bishops started consecrating bishops for the States, English liturgical influence gradually took over from that of the Scots.

If all you want is a joined-up eucharistic prayer, then Cranmer gave us one in 1549. ‘High Church’ factions have often referred back to that as the model to which the communion order should return, and Laud via Wedderburn were attempting such with the 1637 book. The revision of 1552 introduced reception of communion directly after the words of institution, desiring to make clear that the sacrament was made in its reception. In the 1549 rite the words of institution were followed by the prayer of oblation, the Lord’s Prayer, the peace, an invitation, confession and absolution, comfortable words, and the prayer of humble access before the sacrament was received: a situation which was believed to allow too much room for sacramental devotion.

Thanks, Gareth. We could end up debating your semantics. If you are talking about the words said or sung aloud in 1662 then, yes, Anglicanism will find echoes of that continuing into many of today’s English-language Anglican rites (though much in my own province would find little intersection). If you are talking about rubrics and titles of 1662 (for example what 1662 regards as the consecration) then I think I am going to disagree even more strongly with you. Blessings.

When I said that the 1637 Prayer Book was a failure, except that it indirectly led to the 1662 revision, and that its eucharistic prayer was a rejected attempt to return to the 1549 shape, that is not ‘semantics’.

Are you trying to say that the 1637 Prayer Book is ‘normative’ for Anglican liturgy. If so, that’s just wrong. If you are just saying that the 1662 Prayer Book is not ‘normative’, then that is a case of semantics. It is the single most influential liturgical book in global Anglicanism. And I don’t see a need to imagine the book without its rubrics.

Greetings Gareth

Nowhere am I trying to say that the 1637 Prayer Book is ‘normative’ for Anglican liturgy.

BCP 1662 is certainly very influential. And has a particular place in my own province where Scotland’s 1637 (and USA Prayer Books) do not have such a place (save for their influence on our NZ Prayer Book). There is an uncritical assumption in places (many here, for example) that BCP 1662 has a similar place (say) in TEC. That presumption is false.

[Some of the ongoing influence of 1662 BCP in our province leads to misunderstandings of contemporary liturgy. Had we had, here, the 1637/USBCP tradition, those misunderstandings would be less present].

I do not see you sharing that presumption.

Blessings.

I think the problem is with the detachment of a liturgy from its historical context and progression. Ideas that were trialled in the 1637 Prayer Book and were not accepted in the 1662 revision found there way into other Anglican liturgies. However, these ideas lived on not because of 1637 but in spite of it.

I believe that you are using the 1637 book as a cypher for liturgical principles, most chiefly the united shape of eucharistic prayer. It is surely more appropriate to name the 1549 book as the symbol for this principle. That is exactly how the framers of the 1637 book spoke about it: getting back to 1549.

The 1637 book received no use in Scotland; it was a fiasco. The order of later Scottish eucharistic prayers has much more to do with the liturgical outpouring of Nonjurors, who brought the back-to-1549 idea with them to Scotland. Seabury’s Communion Office, which influenced the US 1789 Prayer Book, is a child of Nonjuror liturgy. It is interesting to note that the proposed, but not adopted, 1786 US Prayer Book followed the 1662 order of eucharistic prayer more closely.

This is why I believe you are confusing liturgical principles with a book that happened to embody them.

Holy missing epiclesis, Batman!

“Hear us, O merciful Father, we most humbly beseech thee; and of thy almighty goodness vouchsafe so to bless and sanctify with thy word and holy Spirit these thy gifts and creatures of bread and wine, that they may be unto us the body and blood of thy most dearly beloved Son…”

is significantly different from:

“Hear us, O merciful Father, we most humbly beseech thee; and grant that we receiving these thy gifts and creatures of bread and wine, in remembrance of his death and passion may be partakers of his most blessed Body and Blood: …”

The Scottish Prayer Book is obviously the precursor of TEC’s BCP. Thanks for the history lesson!

I woud be inclined to agree, the Americn Book follows the Scottish form. There was a moment at one of the early General Conventins where Bishop White asked Seabury to lead the Communin office. The first American Anglcan Bishop declined, expaining that he had long had an issue witht he 1662 rite, and expaining the deficiency to White (Provoost having absented himself in a snit). White records that he was supprised by Seaburys’ argument, but found it convincing enough, personally, to accept the Scottish formulation. It can be argued that the post Colonial Prayer Books look more to the 1928 which runs closer to 1637 than 1662.

There was a moment at one of the early General Conventions where Bishop White asked Seabury to lead the Communion Office.

As Anjel said it well, here we have the epiclesis! And this is so similar to the one of the first US BCP!

Manifestly, the Scots were looking broader, towards, maybe, the Eastern Churches, while England was still defining herself in [un]alikeness towards Rome.

I don’t think Bosco is saying Scotland 1637/1674 in normative. I think he’s saying that 1662 isn’t as normative as many Anglicans assume it is.

My thoughts are that 1662 and Scotland 1637/1674 are almost identical in every way except in details that would be noticeable to professional liturgists and clergy. Yes, there is a significant difference in the Communion service, with the Scottish rite clearly teaching a local presence in the bread and wine, and Cranmer inclining more toward a Calvinistic receptionism (which is also why he brought the reception of communion into the centre of the prayer of consecration, to avoid any tendency toward adoration of the elements. Thius is significant today because of what Diarmaid MacCulloch calls the Anglican Communion’s ‘long march away from Cranmer’s theology of the eucharist’.

But the daily offices, the psalms, the collects, epistles and gospels, the occasional offices, and the majority of the communion service are virtually identical. Most ordinary worshippers, used to 1662 and then going to Scotland in 1674 (or the USA after 1928) would I think find the service recognizably the same.

Nonetheless, I agree with Bosco’s main point. 1662 was definitely the majority text, but it is important to notice that there is a significant minority text with a long and honourable pedigree.

Interestingly enough, there is another example of people making ‘global assumptions’ about their version of Anglican liturgy that is very common today, and that is the assumption that the ‘baptismal covenant’ in the 1979 American BCP and the 1985 Canadian BAS is a piece of ancient liturgy that is in universal use throughout the Anglican communion. Of course, it is not – in fact, baptismal rites vary significantly across the communion. But then, we all have a tendency to assume that our form of Anglicanism is normative!

Thanks, Tim, for stating my point clearly for those who were struggling to make sense of the way I put my post together.

The baptism rite is an interesting one also. In our NZPB’s rite, intentionally, no one makes promises “on behalf of the child” – yet many (most?) would still speak of “renewing baptism promises”, reading our own rite through the lens of other (previous) rites (BCP 1662, for example).

Blessings.

I quite agree, Bosco, that it is disingenuous to claim, without qualification, the 1662 BCP as a universally acknowledged Communion-wide standard.

At the same time, my impression is that the story of a “Scottish branch” of Anglican liturgy is often overdone.

The 1637 Scottish BCP foundered with Charles I and William Laud. Its Communion service (alone) found some devotees in Scotland after the Restoration, but among Scottish Episcopalians the 1662 BCP gained ground as an unofficial standard, well into the nineteenth century. The 1764 Scottish Communion Office (there was no 1764 BCP) is not in fact a direct revision of 1637, but a fresh version, in the context of ongoing use of 1662, that incorporates elements from 1662, 1637 and subsequent liturgical experiments and researches (not least the Non-Juror liturgies of the eighteenth century). At various points it refers to “the English Office” for material that is to be inserted.

The first American Episcopal bishop, Samuel Seabury, made a formal agreement with his Scottish consecrators in 1784 that he would use his good offices to introduce the Scottish Communion Office of 1764 into American use. This Seabury did, invoking the ancient authority of a bishop to propose the Eucharistic liturgy of his diocese. Clergy in Connecticut, otherwise using the 1662 BCP (with some necessary deletions in the absence of a King), took up the 1764 Communion Office with some enthusiasm. The eventual American BCP of 1789, however, was a direct revision of the 1662 English book (a fairly conservative revision, too, at least compared with the shockingly Latitudinarian proposed book of 1785, which was rejected by the bishops of the Church of England from whom consecration was sought by Southern US candidates for the episcopacy). Much of the 1764 Scottish Prayer of Consecration was borrowed in 1789, to the extent that the Eucharistic Prayer was made a whole. But the wording was changed in a 1662 direction (the bread and wine no longer “become” anything), and the unique pattern of Anaphora-Intercession was not imitated.

So really, the Scottish and American Prayer Books are both, as a simple matter of historical fact, revisions of the 1662 English BCP. And they continue a trajectory set by 1662 itself: namely, that every authorized BCP revision has tried to incorporate some of the more “primitive” elements of Cranmer’s original book of 1549, but doing so within the framework already in use (i.e. in the tradition of 1552/1559/1604).

Against that historical background, I find that it’s not altogether inappropriate to say, as a kind of canonical shorthand, that the 1662 BCP is indeed a Communion-wide standard: all the other BCPs currently in use derive directly from it; it is the oldest BCP version still in authorized daily use; and it is the official liturgy of the Archbishop of Canterbury, communion with whom (pace GAFCON) defines the Anglican Communion.

Apropos of that last point, it is useful to note again that the American revisers sought to make their work acceptable to the bishops of the Church of England. In Scotland the situation was more delicate: as non-conformists from the Established Church of Scotland (Presbyterian), Scottish Episcopalians were actually subject to legal penalties. An obstacle to the lifting of these penalties was English suspicion that the Scottish Episcopalians were quasi-Romanists. An English bishop anxious to see the end of penal sanctions against the Scots, Samuel Horsley, published “A Collation of the Several Communion Offices” (1792) to demonstrate that the Scottish Communion was in accord with Church of England teaching. The 1764 Communion Office only acquired any canonical standing in the Scottish Episcopalian Church at the Synod of Aberdeen in 1811. And even then they permitted the 1662 Communion Office to continue in use in those congregations that preferred it.

So here we see that doctrinal conformity with the 1662 BCP was very much in the frame for the American and Scottish Churches, precisely as a standard for sacramental communion.

Thanks, Jesse. I think if we debate the details of your points we are going to degenerate into arguing about when something is “overdone”, the difference between a “revision” and your “direct revision”, and different ways to draw a family tree. I stand by my point: the truncated BCP1662 “Eucharistic Prayer” (read “consecration”) is, for example, not normative for Eucharistic liturgy or doctrine in the Anglican Communion. The 1549/Scottish1637/1764ScottishCommunionOffice/AmericanPrayerBook line has a voice in the Anglican Communion. That voice may not have been as large or as loud as 1662BCP, but it is an authentic lineage that is, in revised and renewed contemporary liturgy in the Anglican Communion, the voice that has come to dominate. Rightly IMO. Blessings.

If all we are talking about is the shape of the eucharistic prayer in early Anglican liturgies, then the basic ideas are in Cranmer’s two Prayer Books, of 1549 and 1552. The latter book rearranged texts, and deleted a few (e.g. Agnus Dei), so that the words of institution (thought by some to be the ‘moment’) was immediately followed by reception. The receptionist doctrine of the sacrament was the guiding principle, and was not accepted by all. Since the publication of the 1552 Prayer Book, some have yearned for a return to the more traditional shape of its predecessor. In the 19th-century Church of England, the desire to return to the 1549 Communion Order was still alive and well. The fact that the political fiasco of the 1637 Scottish Prayer Book exhibited the 1549 shape says nothing more than this principle was being tested. Later Scottish and US Communion Orders are not descended from the 1637 book, but Nonjurors bringing the old 1549 ideal with them.

Thanks, Gareth. The 1662 revisers clearly did not understand the 1552 shape you describe of receiving communion in the middle of the Eucharistic Prayer at the point when many had thought the words were consecrating. They introduced an “Amen” after the institution narrative, concluding the prayer, and called this truncated prayer “the Prayer of Consecration” reinforcing the very point that you are clear 1552 was attempting to avoid. I continue to hold my point: while this understanding may have particular weight in some provinces (including my own) it is not needing to be understood as the normative Anglican-Communion-wide position. Blessings.

Yes, 1662 made these modifications, adding the word ‘Consecration’ to the rubrics and an ‘Amen’ at the end of the words of institution. These were Jeremy Taylor’s modifications of what is otherwise the 1552 prayer. He could not have persuaded the church to adopt the 1549 shape. He may not have accepted the theology of the 1552 shape, but was burdened with it. Are you saying that the same ‘broken’ shape of the eucharistic prayer necessarily means that the eucharistic theology of these two books’ framers are the same?

The various revisions of the Prayer Book are products of their religious and political contexts. The 1662 Prayer Book was produced by committee and shows the marks of compromise, for good or for ill.

As the 1662 book is still in use (officially) in England, there is perhaps a greater tendency to think it witnesses to core beliefs. It is the liturgy on which most Anglican provinces were built. In England, it is normative in the sense that Canon A5 mentions it as one of the foundational documents of doctrine. In global Anglicanism this is clearly not the case, but the 1662 book remains the liturgical document with the greatest impact on the Communion.

Yes, I think we’re in substantial agreement there. The “second voice” isn’t really 1637/1764: it’s 1549. W. Jardine Grisbrooke’s book on 17th- and 18th-century Anglican liturgies (just Eucharist) makes that point fairly clear: every revision, including 1637, has been trying to restore elements of 1549. (For example, we note that the placement of the Invocation in 1637 is that of 1549, not the “Eastern” location of Scottish 1764 and American 1789, which we owe to the influence of the Non-Jurors.)

Here in Canada, our 1959 revision hinged on the interpretation of the “Solemn Declaration” made at our first General Synod in 1893. That declaration said:

“we are determined by the help of God to hold and maintain the Doctrine, Sacraments, and Discipline of Christ as the Lord hath commanded in his Holy Word, and as the Church of England hath received and set forth the same in ‘The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments and other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church, according to the use of the Church of England; together with the Psalter or Psalms of David, pointed as they are to be sung or said in Churches; and the Form and Manner of Making, Ordaining, and Consecrating of Bishops, Priests, and Deacons’; and in the Thirty-nine Articles of Religion; and to transmit the same unimpaired to our posterity.”

The question was, “which Book of Common Prayer”? In 1893 it probably meant 1662. But in the 1950s we decided that it included the whole BCP tradition, going back to 1549. Hence, for example, we recovered an optional anointing of the sick.

Agreed, Jesse. In the very comment that you are responding to I speak of a “1549/Scottish1637/1764ScottishCommunionOffice/AmericanPrayerBook line” as being a voice alternative to 1662. Just as I am not wanting to give the impression that 1637/1764 is a new voice ex nihilo, so one could similarly place 1549 as part of an earlier lineage. Blessings.

And another thing…. 🙂

The upshot of this very enjoyable discussion, it seems to me, is really an illustration of how the emergent provinces (particular churches) of what later became the Anglican Communion possessed, and exercised, authority to revise their own liturgies, and that perhaps it is surprising that other provinces did not follow their example until quite recently. (My supplementary point was that both of these proto-provinces happened to be applying their blue pencils to the book they were already using, namely 1662, while also mindful of earlier Anglican precedents and of the need and desire for approval by the mother church.)

But being a bear of little brain, I am only just now noticing, Bosco, that what you specifically have in mind to oppose is a position that I have actually never met before, namely a claim to special Communion-wide status for the 1662 Eucharistic “shape”, which, as you point out, is a bit of a platypus (neither Cranmer nor Gardiner, if I may put it that way). Is this a point of view commonly urged in other provinces? It is quite new to me.

Your point is very well taken. I had been thinking in an entirely different vein:

Samuel Seabury famously declined (to the point of discourtesy) to preside at a Holy Communion in the US where the 1662 rite was to be used. By way of explanation, he gave his opinion that the 1662 Prayer of Consecration was probably not a valid Eucharistic Prayer.

In other words, he held the very opposite attitude to the one you have been opposing. Not only was 1662 not normative, it was insufficient. Did he really believe (as Rome still officially teaches) that the Church of England had continued without the Eucharist all that time?

By contrast, I have encountered some evangelicals who appreciate the 1662 BCP as a recognized “minimum standard” with which they are comfortable. Against Bishop Seabury, they could say, “Our tradition guarantees that this is a sufficient liturgy for the Eucharist, and we feel no need to go further.” (Or in the book’s own words, originally applied to the 1604 BCP, it “doth not contain in it any thing contrary to the Word of God, or to sound Doctrine, or which a godly man may not with a good Conscience use and submit unto, or which is not fairly defensible against any that shall oppose the same”.)

For example, a break-away “Anglican Network in Canada” parish in Ottawa advertises that it uses a slightly adapted form of the 1662 Communion (instead of the Canadian 1959 version), because 1662 reflects “the mature spirituality and wisdom of the English Reformation”.

On this view, 1662 can perhaps claim a capacity to function as an “instrument of unity” across the whole vertiginous spectrum of Anglican churchmanship, in a way that other version perhaps cannot. (Anglo-Catholics and liturgiologists may not be thrilled with 1662, but they are mostly willing to admit that it at least “works” ex opere operato — and, in the case of conscientious priests, are willing to use it themselves when it is a parish’s customary liturgy.)

And that is one of the reasons that I have in the past several years been making an effort to “see myself” in 1662, instead of constantly seeing how it fails to satisfy. It has been a surprisingly easy task: just reading up on what Richard Hooker understands by the the word “participation” (cf. “partakers” in 1662), for example, opens up a broad vista of meaning.

I am now to the point where some of the later tinkering (especially in our Canadian book) strikes me as hopelessly shallow when compared with that “prose which can be spoken generation on generation without seeming trite or tired — words now worn as smooth and strong as a pebble on a beach” (D. MacCulloch).

I have come almost to think that the Anglican Communion’s attitude to the 1662 BCP ought to mirror its position on Confession: “all may, none must, some should”. And I rather doubt whether there are any other serious contenders for that a status.

In my U.S. History of Religion we went over the pilgrimage and creation of the Scottish church of America, the Presbyterians with a fine tooth comb. As a direct descendant of those same people and their beliefs (great-great grandfather to deacon father of the church) they never do anything halfway. Bishop Seabury was in so much competition with the CoE transplants that his descendants moved the church to the West where they converted Indians as well as the white man with more success. The way they wrote their eucharistic prayer with such beautiful, poetic, straitforward simplicity is why it is well liked and their church is widespread and accepted all over the U.S. and beyond.

This has been a really interesting discussion, regardless of one’s perspective!! (Though, I generally agree with Fr. Bosco)

I think that one of the principle reasons why a lot of people in the Anglican Communion view the English 1662 Book of Common Prayer as “normative” is that it is the only “official” liturgy they have collectively experienced (alternative service books notwithstanding). Our history in America over the past 400 years gives us a somewhat different perspective on what is “normative.” During the Colonial Period here Anglican services were performed from the PBs of 1559 and 1604 as well as 1662. And, of course, we Episcopalians were the first Anglicans outside of the British Isles to revise the BCP (1785 and 1789) as well. So, for most of us, 1662 is decidedly “not normative.”

Speaking as a High Churchman, I’d say if there is a basic Anglican “model” for the liturgy it is the 1549 book, rather than that of 1662. Certainly the more Catholic revisions in all of the subsequent Prayer Books harken back to the spirit of 1549, including the various Scottish liturgies which have influenced the liturgies here in the USA. My reading of Charles Wheatly’s “Rational Illustration of the Book of Common Prayer” (1710/14) tends to support this view, too.

In terms of “normative,” I think that there are as many departures from 1662 here as there are similarities.

Take the Scottish Usager custom of the Reserving the Blessed Sacrament for the sick, shut-in and dying, for example. Many Episcopalians have long maintained that Bishop Samuel Seabury worked to normalize the Reservation of the Blessed Sacrament in our Church from the very beginning of his episcopacy by inserting a specific clause into the 1789 Prayer of Consecration for the express purpose of providing for Reservation on the Scottish model.

And not all of the early American PB revisions were from the Catholic end of the spectrum viz 1662. Latitudinarians, too, had their influence.

In the 1785 Proposed Prayer Book of the American Church, the procedure for auricular confession was removed from the 1662 Office for the Visitation of the Sick. Instead, in a shift of emphasis, the outline structure for reconciliation of a penitent was provided for in the Form for the Visitation of Prisoners, which was taken, in large measure, from the Prayer Book of the Church of Ireland.

And, of course, Americans simply excised a number of features from the English PB of 1662 in our books. None of the American Prayer Books have ever had a “Black Rubric,” mandating specific interpretations of the Real Presence, for example (Nor have any of the Scottish, I believe). Likewise, our clergy have never been restricted by an Ornaments Rubric in what they can wear, or how they can apparel an altar, etc. And neither clergy nor laypeople have had to “subscribe” to the Articles of Religion. (For many years, we had no Articles of Religion whatsoever!)

Kurt Hill

In snowy Brooklyn, NY

Thanks, Kurt, for your balanced comment from the American context expressing more clearly the point I may have said clumsily. Blessings.