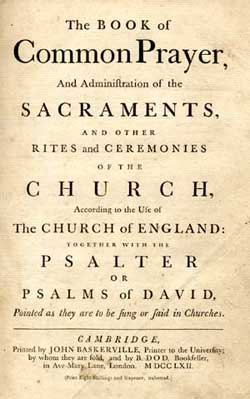

No sooner has the 400th anniversary of the King James Bible passed but we are in the 350th anniversary year of the 1662 Book of Common Prayer.

No sooner has the 400th anniversary of the King James Bible passed but we are in the 350th anniversary year of the 1662 Book of Common Prayer.

PDF Celebrating 350 years of the Book of Common Prayer

Obviously the 1662 version was not the first Book of Common Prayer, nor the last one. It is not infallible, nor inerrant. Some things are done better in earlier Prayer Books. Much is done better in later Prayer Books. Nonetheless, like the King James Bible, it sets a standard in its day which is the quality that we should be working at in our own time and context.

Just like clinging to the King James Bible in our own time is the very opposite of what those who worked on it four centuries ago would have intended and expected, so similarly clinging to the Book of Common Prayer 1662 in the twenty-first century would completely surprise those who worked so hard to provide a liturgy that spoke directly to the context of their time.

Nonetheless, some parts of the 1662 Book of Common Prayer have survived surprisingly well and continue into our present day in the same way as parts of the King James Bible have survived.

Principles undergirding the Book of Common Prayer, the centrality of the whole of the scriptures in prayer, the spiritual disciplines of the daily office and weekly Eucharist, the value of common prayer, the drawing on the liturgy of the early church, etc. continue, IMO, to be of deep value today – and we abandon these at our obvious cost. So let us commence this anniversary year allowing the spirit of this landmark book to continue to challenge us.

During a period of ecclesial abandonment, the BCP 1662 become a portable church for me and sustained me in the faith in a period of exile.

The Daily Offices kept me nourished by the Word of God. I learnt that the BCP pattern was more important than the full content and discovered the various time-hallowed ways of abbreviating, shortening and combining the services without violating basic rules of liturgical order.

On Red Letter Days and Sundays I kept in sync with the liturgical year by celebrating the Service of Ante-communion (aka a ‘Dry Mass’ or the Lord’s Supper up to when a priest is absolutely necessary, ie the end of the Prayer for the Church Militant).

I learnt that Mattins, Litany and Ante-communion had been the staple of C of E worship on Sunday morning for centuries and could be a worthwhile way of keeping the Lord’s Day if one was prepared to put in the time and effort.

I even celebrated the Service of Commination on Ash Wednesday and enjoyed its fire and brimstone Exhortation with the added frisson of knowing, that like most robust expressions of faith, it had been banned from public celebration, at least in the Anglican Church of Or.

I started to welcome second-hand BCP’s into my liturgical retirement village and would carry a pocket BCP around with me like a talisman. Whenever I was in a waiting-room or queue I’d turn to the Psalms (how good is Coverdale’s translation? – 477 years old and still gracious in rhythm and cadence) or read the Sunday Collect, Epistle and Gospel. No other book has been printed in such portable versions with such legible print and good binding.

Anglicans do well to remember that, other than our Saviour, we have no founding personality who looms large over our tradition, nor a charismatic figure leaving his or her mark on our ecclesial community. We have a public prayer book: a comprehensive liturgical text which has shaped and structured our hearing of God’s Word and celebration of the Sacraments for over 400 years.

In its short compass we go from Advent Sunday to All Saints’ Day, from birth to death, from the apostolic ministry to the principles of reformed theology, from curious almanacs to work out the most pivotal date of the Christian year to a lectionary of readings conveniently linked to the calendar month. All in a book which is 75% derived from Scripture and retains Cranmer’s matchless translations of those liturgical haikus of the Western church: the collects.

In this commemorative year I hope to participate in a full BCP Mattins as I have yet to experience this service. I wonder if I might also hear the BCP Litany as this would also be a first. I’m resigned to being born 100 years too late to experience the full force of the Commination Service in a congregational setting – liturgy at its most hard-core!

Thank you, Steve! Your comment is a wonderful, worthy summary – if only the spirit of your comment was embodied in contemporary Prayer Books. I wonder if you might say a little more about “the various time-hallowed ways of abbreviating, shortening and combining the services without violating basic rules of liturgical order” (or point us to sites where these are described for readers). I might add that the BCP brings the (Benedictine) monastic spirituality beyond cloister walls for all. And I don’t know if you realise that Carthusians of old had an extra office, Officium Missae, Missa Sicca or the Dry Mass. Blessings.

Too true, Bosco. Benedictine spirituality pervades Cranmer’s system. I think it was the Scottish liturgist Bishop Dowden who once declared that the Ante-Communion service might be one of the oldest forms of liturgy known to the church!

With regard to the flexible use of the BCP, I have no sites as references as I was thinking of the various approaches towards simplifying the BCP (especially the Daily Offices), found chiefly in books for popular devotion such as the pre-Puritan English Primers and Bishop Cosin’s Book of Hours of Prayer.

Proctor and Frere in A New History of the BCP (1929 edition, pg 223) refers to the custom of ‘Short Morning Prayers’ in the 17th century being celebrated in churches at an early hour. Popular twentieth century office books (often for church school use) provided Shortened Mattins and Evensong orders which after the opening versicles and responses, provide a simple structure of a single psalm or psalm portion, one Lesson, a single canticle, Apostles’ Creed, Lesser Litany, Lord’s Prayer, Preces and collect(s). This is very similar to how the Church of England restructured its Daily Office in its Alternative Service Book 1980.

The extremely popular green Shorter Prayer Book incorporated many features of the 1928 BCP but also gave outlines of how to combine Mattins with Holy Communion (conclude Mattins after the second canticle and begin the Communion Office, pg 12); how to simplify the Litany (omit some of the suffrages ad libitum and omit the entire Supplication, pg 29); and how to use a form of the Litany as a preparation for Holy Communion, pg 29.

These approaches and the desire for flexibility eventually resulted in the so-called Shortened Services Act of 1872 (or The Act of Uniformity Amendment Act). The way the legislation envisaged the simplification of the BCP violated many liturgical norms but it gave legal authority to reshape the BCP orders when pastorally appropriate and has had long lasting effects despite some of its dubious directions (eg the omission of the integral second Lord’s Prayer at Mattins or Evensong).

In this 350th anniversary year of the BCP, it’s worth noting how the Shortened Services Act in 1872 unbound the strictures of BCP worship and gave room for a form of liturgical innovation. New non-eucharistic services could be compiled for the first time as long as their contents derived from the Bible and the BCP. The Act of Uniformity was giving way to the freedom of the Spirit – in an Anglican sort of a way.

Thanks, Steve. Blessings.