At the Inter Diocesan Conference (IDC), the Tikanga Pakeha, pre-General Synod meeting, the Tikanga Pakeha strategic plan for theological education(PDF) was received.

It is hard to believe that this document was presented (and received) without embarrassment. One vicar said to me, on seeing this document, that there is more in his parish’s documentation about training in his parish than this paper provides for the province!

As this document explicitly states, this sets the “priorities [which] are used to guide all Tikanga Pakeha funding applications”. We are talking millions and millions and millions of dollars! Beyond the financial dimension, I see the future health, or otherwise, of the church in this document.

The document starts by saying that this strategic plan is the result of being “developed over several years” by the Tikanga Pakeha Ministry Council.

The Anglican Church has serious issues; not least IMO because it is succumbing to the cultural worldview that church is but one activity equal to, say, model railways, to which one can devote one’s discretionary leisure time. We are a hobby. And the rapid hobbyisation and amateurisation of church is reflected in, and now driven by, the abandonment of disciplined training of our leadership.

The issue is exacerbated by our church’s systemic decision not to gather statistics. We have no idea, as a province, of the level of training, study, and formation of our clergy. Even as dioceses, which diocese would be able to provide such information for the diocese? More general information is also inaccessible. Even senior clergy generally have no real idea what is happening at St John’s College (supposedly our provincial seminary, with a trust fund in excess of $320 million – is there another Anglican theological college anywhere in the world so well endowed?!), or who is training where from their own diocese.

The strategic plan, while mentioning St John’s College, does not even make an allusion to the reality of the scathing Sir Paul Reeves/Kathryn Beck Commission Report on St John’s College and the two-year suspension of the canon on St John’s College, a canon which has just been suspended for a further two years.

Ordination with minimal training, formation, and study is rampant. A diocesan ordination with around 30 being ordained is not unknown. It may be difficult for readers from beyond these shores to appreciate that Anglicans in New Zealand have no agreed standards for ordination. If any diocese has a written standard – let’s have a link to a copy in the comments below.

Have a look at the strategic plan, after which I will make some further comments:

TPMC Mission and Ministry Priorities 2012

- The response may be that this meagre strategic plan is for the whole church not just clergy formation, but I don’t think that starting with the Anglican 5-fold mission statement is appropriate. The last thing I want to see is the return to the situation where the priest was the minister. Clergy may be important to enable the mission and ministry of the church; they are not there to do it all.

- I have, several times, criticised the inadequacy of the 5-fold mission statement. Worship is not an optional extra to the mission of the church – it is central. The omission of worship from the mission statement translates into defective strategic planning for church leadership formation. Liturgical leadership (training, formation, study) should be an essential dimension of church leadership training.

- The lack of liturgical leadership formation, study, and training is reckless. Recent discussions have underscored that those responsibly seeking ordination cannot access a single liturgics paper for a degree. This is incredible.

- It is, for me, beyond comprehension that in this document there is no reference made to the Ordination Liturgies of A New Zealand Prayer Book He Karakia Mihinare o Aotearoa. These present IMO one of the best, succinct expressions of ministry, and would surely be ideal for developing strategic planning for formation for the ministries that they describe in the manner we are bound to uphold.

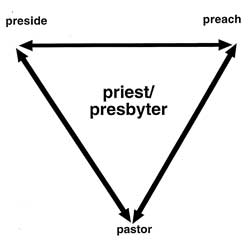

- Rather than the three overlapping foci of the strategic plan, I suggest the foci I provide in my image at the start of this post (preside, preach, pastor) as alternative (or further?) foci around which formation, training, and study for church leaders could be strategically organised.

- Astonishingly, the church’s strategic plan makes no reference to the work of TEAC (Theological Education for the Anglican Communion). TEAC was established at the meeting of the Anglican Primates in Gramado, Brazil in May 2003 (building on previous work) and regularly reports to the Primates’ meetings and to the Anglican Consultative Council – theological education is seen as a priority in the Communion. TEAC has produced a number of very helpful documents.

This is the third in a series of posts reflecting on General Synod Te Hinota Whanui 2012 (GSTHW) of the Anglican Church in Aotearoa, New Zealand and Polynesia. It is written from the perspective of one not present at that meeting.

The first post looked at the attempted revision of A New Zealand Prayer Book He Karakia Mihinare o Aotearoa.

The second post looked at the making of a collection of rites, for the Lent and Easter Seasons, a formulary of our church.

Hi Bosco,

The documentation being criticised here can be improved.

Nevertheless I part from you in a form of “shock/horror: how can our tikanga have arrived at the situation it is in?” response to the diversity and/or superficiality of our formational processes as though our tikanga as a whole is responsible for the muddle (or even mess) we are in. Our tikanga is made up of seven dioceses. Those dioceses have evolved lives of their own. All documentation attempting to draw together what is common to our aspirations are necessarily going to be of the kind you critique here: patchy, drawing on motherhood and apple-pie Anglican statements, and stressing generalities to the point of banality. If you want to see change then a whole structural change of our tikanga from a diversity of dioceses with dispersed decision-making across them model to something, frankly, more akin to a Roman or even Destiny model: one (arch- or papo-) bishop to rule us all.

I would like to make a further point out of my experience of working under three bishops in two dioceses and participating in TPMC for nine years: bishops ordain, sign licences, make appointments. If they are ordaining people prior to completion of qualifications, let alone prior to completion of ‘adequate formation’, and/or licensing people to appointments with insufficient prior experience and qualification for the post, then they are responsible for those decisions. But I stress “if” because I am sure they would debate with the likes of you and me, case by case, why they have made the decisions they have made. To a collective observation that we have arrived in the present with a gradually dumbing down from what the past once was, they might say ‘Welcome to the reality my episcopacy faces.’

In short: I can broadly speaking agree with you that we are not in a happy situation, but I differ with you as to whether the remedy lies more with bodies such as TPMC or General Synod or the St John’s College Trust Board and the like or more with the structuration of our church and the power of individual dioceses to carve out their interpretation of the demands and supply of ministry.

I would urge care about likening what is going on in respect of hobbies. We continue to have people offering for service in the church who are not embracing a hobby, rather they are engaging in a sacrificial change of life’s direction.

Thanks for your thoughts, Peter.

I disagree very strongly that the only alternative to this strategic plan is “more akin to a Roman or even Destiny model: one (arch- or papo-) bishop to rule us all.”

If these 7 dioceses have strongly evolved lives of ministry formation, training, and study which are so energetically different from each other that no consensus can be achieved other than what you are describing as “motherhood and apple-pie Anglican statements, and stressing generalities to the point of banality” (banality that the document claims took several years to develop and sets the priorities for millions and millions of funding applications), let’s see documentation from one of these robustly conscious dioceses linked here and add that into the discussion.

Furthermore, if the 7 pakeha dioceses are so different from each other that no significant agreement can be reached about ministry training, formation, and study there needs to be much deeper discussion about the movement that is current between dioceses of clergy.

Blessings.

Did you lot steal apple pie from the Statesonians? I love apple pie and chocolate creme pie and lemon meringue pie and peach cobbler and strawberry cream cheese tort and…

These things don’t exist in Mexico. No one here would have the foggiest notion of how to make a pie crust or even what one is.

I would be the first to agree, Bosco, that dioceses have made too many decisions about what is acceptable training and formation as though their diocese is the only diocese in which their deacons/priests will ever serve. But clergy do move and that definitely highlights the need for greater commonality.

But I would still push some way towards the bishops and their collective responsibility: when they agree together to pursue greater commonality, then TPMC might have a chance of hastening progress, SJC might come into stronger reckoning as a place where more rather than less clergy go for training, and ministry educators might have clearer direction about what they should and should not be doing.

I think we are agreeing, Peter. But why are statements akin to what you just made not part of what is presented to the IDC?! Why does the TPMC present “motherhood and apple-pie …stressing generalities to the point of banality”? Why not a bit of this pushing that you mention in your comment in the actual document? Where is the pushing actually happening? & furthermore, if we are synodically governed, is there some culpability in the governance – not just the bishops on whom you are placing all the responsibility? Blessings.

Thank you, Bosco, for this reminder that the Church, in its ministry formation plan, ought make significant reference to training in the art of worshipful Liturgy for prospective ordinands.

Not everyone has experience of the most effective ways of using Liturgy as Formation in the parish before entering Saint john’s College. And, from my own experience there over thirty years ago – when there were probably more students interested in Liturgy and who formed the basic congregations for the Daily Eucharist – there was nothing in the curriculum that enabled budding priests to perform the liturgical functions that would be expected of them after ordination.

For me, still active in Eucharistic ministry though officially ‘retired’, worship has always been at the heart of what I perceived to be the Mission of the Church. Christ’s summary of the Law was that we should love (worship) God with all our hearts and minds, and then, love (honour) our neighbour as ourselves. All Mission surely should proceed from this. Without the basis of adequate worship of our All-Holy God in Trinity, we may just be promoting song-fests and providing popular secular entertainment.

Thanks, Fr Ron. The point to go with your comment is that those who go to St John’s for training are now very much in the minority. Blessings.

If folks aren’t going to your province’s seminary, where are they getting training? Are they just “reading for orders” locally?

Firstly, Brother David, we don’t know. As we keep no statistics – we don’t know. Peter Carrell, who is far more in touch with all this is indicating that our 7 pakeha dioceses are so diverse that what happens in one is so different to what happens in another that no commonality can be found between them – hence, to speak of “where they are getting training” is impossible. No one has yet taken up my challenge to provide a diocesan document of their policy for ordination formation (and, I haven’t checked the stats – but somewhere between 500 and 1,000 have now read this post). Blessings.

Bosco, from far away (USA) it is hard to imagine that the church in NZ does not have agreed-upon standards of ordination. The ECUSA has reasonably good standards for such, though similar to you no doubt, their application varies from diocese to diocese. Our church has 110 dioceses (way more than 7) and we manage more or less without a college of cardinals and pope to maintain these standards.

I too worry though about the creeping de-professionalization of ordained ministry. I know wonderful priests who did not get seminary training and plenty who did go to seminary but aren’t very effective. But for me, I can’t imagine that I could have been able to focus on and discern my formation during seminary if I was also still engaged, more or less, fully in my former secular life.

I will say that my seminary (Bexley Hall) was strongly focused on liturgy and formation in the pryer book tradition and strove to be inclusive of the whole spectrum of anglican worship. I’m sure the Dean would be happy to consult with St John’s if they need some help :).

Jon White

To be clear, Jon – to have agreed-upon standards of ordination (as per TEC) and to have some variety in the application of those standards is one thing. What we have is absolutely no agreement. And I am not talking about across our three Tikanga (cultural streams), but within Tikanga Pakeha (the more “European-type” cultural stream). Numbers in that Tikanga are probably akin to a good-size CofE diocese. Blessings.

There are a HANDFUL of ECUSA dioceses where it is common to see “locally raised up” Priests serving parishes on a part-time or volunteer basis. The one diocese I know of where this is common is the Diocese of West Virginia, which serves one of the poorest, worst educated, and most sparsely populated states in the United States. Before the 2009 General Convention priests without seminary training were called Canon 9 priests, and could not be paid for their ministry. At the General Convention TEC decided that creating a caste of second-class priests went against the theology of holy orders, and made all priests equal before the canon-law. Nevertheless, the vast majority of TEC ordinands continue to possess MDivs, though I suspect that a lot more of them came from commuter students and/or from non-Episcopal seminaries. In particular Episcopalian Evangelicals seem to favor Duke Divinity School, which is affiliated with the United Methodist Church. For that matter, while the Diocese of Southern Ohio’s seminary, Bexley Hall, is technically separate from Trinity Lutheran Seminary, since the two institutions share a common faculty, a common building, a and a common course selection, this seems to be a distinction without a difference. Obviously there are separate Lutheran and Anglican courses on the Reformation and liturgics. Bexley Hall has a separate dean and its students receive letter grades rather then the pass/fail marks the Lutherans get.

Thanks, Whit. We have what is called “Total Ministry” or “Local Shared Ministry” like that here; with parishes in the urban area of NZ’s second largest city with no stipended priests – but having come through the “Local Shared Ministry” process leading to ordination… Blessings.

A good discussion.

The paper does seem remarkably sparse, I agree.

One of the issues, it seems to me, is a changing sense of what clergy ‘do’ and for whom they do it.

Your triad of preside/preach/pastor is useful, and in theory should guide some ideas about what preparation is needed for each of those functions (and the distinctive combination of those functions that is found in priestly ministry in the Anglican context). One thing I wonder, in reality, is the relative weight given to each, and the expectations of each. Many in my diocese are ordained without formal undergraduate preparation in ministry or theology. The question I wonder is how this impacts upon their abilities to feed their community through preaching? How does this impact on their capacity to ‘do living theology’ with those they pastor? I am all for flexible ministry development and formation, but I’m also for a good understanding of necessary competencies and preparation to meet those.

I think, myself, this speaks to exactly what you point to – the hobbyfication of church life and Christianity (one good, interesting thing among many others). An irony I often see in my own church is that my fellow Christians often know far more about their other hobbies than they do about Christianity! Our formation programs for every Christian are so poor as to be hopeless.

Hi Bosco

Thanks for raising the issue of ordination training standards. I’m currently training for ordination part time alongside my lay work for the church but at a college that also has full time students. The Church of England as incredibly precise guidelines and is currently undergoing a review as well. They select on the basis of these http://www.churchofengland.org/media/56413/Summary%20of%20Criteria.pdf and throughout training we as ordinands are expected to reflect on how well we are doing at each of the nine criteria.

Jon, you queried whether training would have been possible if you had still been in your secular life and from my perspective – juggling both – I can understand that BUT I also see the full time residential students at our college and friends who have left other colleges get so caught up in the studies that they are disconnected to some extent from the rest of the world and sometimes I think the grounding of normality helps me. I also explore my vocation as a growing thing rather than through three years outside of my normal life.

The Church of England review (of which I’m not a part) is looking at what things should be covered in training and I know some of us have put forward pleas for things like training in understanding youth work, education, chaplaincy etc but I’m waiting to see what they come out with.

Thanks so much, Sarah, for adding these thoughts from up-to-the-minute situation in CofE, a church far far larger than ours. If you can point us to links about the review, I would appreciate that. Blessings.

The question of clergy formation is indeed a complex one. We are in a situation now where the vast majority of ordinands are coming along having already had careers in a variety of areas and with families of there own. Thus the model of residential “seminary” formation is not practical or even appropriate. My own diocese has a requirement that a B.Th is the normal starting point for ordination and this can be obtained from a variety of sources (not all Anglican) Whilst the B.Th provides a solid grounding in theology, scripture and ecclesiology, it is unable to provide students (as seminaries of the past were able to) with an understanding of “culture” in the Anglican context. This,I believe, is the challenge that is facing us here in my diocese.

You do not indicate, Fr James, which diocese you are writing from. Nor do you give any indication why residential seminary formation is neither practical nor appropriate for those who have had a previous career and a family. When I went to St John’s College from this diocese, there was no question of an alternative way of ordination preparation offered; all of us had had a previous career; all of us gave up those careers; all relocated their families to St John’s. Blessings.

Bosco,

Sadly (and my apologies for swearing) SNAFU.

I have had a discussion with a senior member of clergy who did suggest that it is rare a diocese has a decent formation program.

Hopefully in your case the province is setting minimums (even if they do need improving).

Dave

Dave, are you saying it is a rare diocese/province that has clear standards and goals, or are you saying these are rarely implemented rigorously? I am not aware of my province setting minimums – and comments on this thread suggest, from Peter with far more experience in these discussions than I, that it is not currently possible. Blessings.

Hi Bosco and other commenters,

On a more technical note, are any experiencing what I am experiencing on this thread, namely that having ticked the box to receive alerts to further comments being made, I have not received alerts … I know Bosco that you have been experiencing some difficulties on your site recently. Might this be another glitch?

Oh dear 🙁 Thanks for letting me know, Peter. I would love to hear from others if that is your experience. Also, from anyone who knows what would cause this latest glitch. And I will look into it too. Blessings.

This time some serious thoughts. I have studied in two different formats for seminary. The first was a residential seminary at SMU in Dallas, TX that was very traditional as far as how subjects were taught. Although there were students who took course work part time while they cared for families and worked full or part time secular jobs, the majority of students were engaged in full time studies. Many of us lived in the graduate dorms or apartment buildings on campus. Some who lived near by commuted.

The education in the US and Canada required by most main stream Christian denominations for ordination, is a Master of Divinity degree (M.Div.) from a seminary accredited by the Association of Theological Schools in the United States and Canada. This is a graduate level, professional degree that has the prerequisite of an accredited bachelor’s degree.

The difficulty for part time students in this setting is that the course catalog and the schedule of courses each semester were strictly geared to the schedules of the full time students. The typical M.Div. is three years of course work, with 1 or 2 semesters of field placement in a ministry setting between the 2nd and 3rd years. So it usually takes 3.5 to 4 years to complete. Field placement is usually a paid position on the pastoral staff of a parish (not necessarily of the same denomination as the student) or as a chaplain in an institutional setting; hospital, hospice, school, etc. Because the rotation of courses offered at this type of seminary is geared for the full time student, the part time student may have difficulty in getting the required courses that they need conveniently in the order that the courses are required to be taken (Theology 101 has to be taken as the prerequisite to Theology 102.) This may inconveniently extend the number of years required for the part time student to complete the degree.

The other seminary that I attended was an independent, non-resident seminary in Seattle, WA that was specifically geared to the part time, commuter student with a family and a full or part time job. The course work was offered on a monthly basis, with credits on the quarter system. (The universities of most countries in North America are either on the quarter system, where 3 full time quarters make an academic year or the semester system, where two full time semesters make an academic year.) In this seminary, students took 1 or 2 subjects a month with classes either on Monday & Wednesday, or Tuesday & Thursday with a half Saturday and a full Saturday. At the end of the month the student took the final exam and received the grade and a quarter’s worth of credit for the course. The typical subject, Old Testament for example, may require 3 months to cover the full curriculum.

This system of education is based on research in the US originally conducted by the US armed forces regarding training working adult students with limited time to study and other distractions in their lives. The research stated that students learned and retained more if they studied only one subject at a time. My older sister completed her MBA/JD at a private university in California, National University, which was originally based on the same US military findings.

Thanks for providing concrete examples of different models of quality theological education, Brother David. Blessings.

Church of England Review report came to Synod in July – details start here – and lead to lots more documents via the link in the pdf.

http://www.churchofengland.org/media/1280742/gs%201836.pdf

Hope it’s useful!

Thanks, Sarah. Blessings.

Church of England Phase 2 report here : http://tinyurl.com/crcw4xq

I have to say, having begun my training in New Zealand, and completed it in Wales, that the concern that there are ordinations with minimal training, formation and study is a very valid one. I was expected to do two years training in St David’s diocese even though I already had done one in New Zealand, and had degrees in theology and canon law. The principal difference was that I was on a full parish placement over here, fully integrated into the life of the parish, and entrusted with taking services of morning prayer (where these were our principal Sunday services). Having said that, arrangements over here are, at diocesan and provincial level, far from perfect, like in New Zealand. At least I found the Diocesan Training Programme in Auckland to be helpful, but I was disturbed that one ordinand was ordained a deacon almost immediately on the grounds that he had been a lay youth minister – he had no formal theological training and no formation – and since I left New Zealand two years ago I have discovered that several of my colleagues on the course have been ordained – one a priest already (and she evinced minimal knowledge of Anglican liturgy or tradition during the time I knew her). This worries me greatly, especially when, as has been pointed out, St John’s College has enormous resources, quite sufficient to fully train all ordinands. But then, St John’s has long preferred teaching feminist theology over patristic theology – largely why I did my basic theological training elsewhere, sadly.

Thanks for your concrete examples, Noel. NZ has just authorised “Charter Schools” where people who are not trained as teachers can teach. It seems to me they got the idea from the Anglican Church where I know of people with little Anglican background, some theological knowledge, ordained deacon and running a parish receiving in-service local occasional training. From this distance, Auckland appears at the better end of the training spectrum. Blessings.