Rubrics are the instructions given within a printed service. I have been proposing a model of liturgy (communal worship) as being like a language – the language of liturgy being primarily the symbols, signs, gestures, etc. accompanied by words.

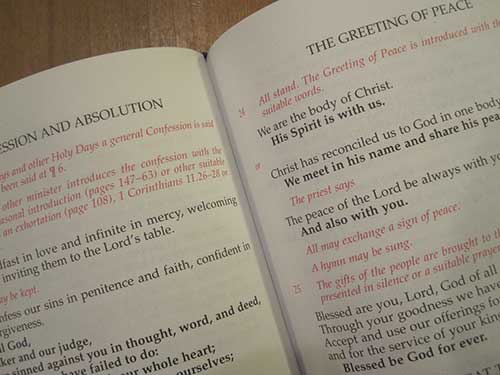

Rubrics, traditionally, were coloured red, although now they are commonly simply printed in black italics. There is a catchcry, “Do the red. Say the black.” There is much value in that, but I want to take a slightly different tack following my grammar model.

Following my model, I want to think of rubrics as being ‘descriptive’ more than ‘prescriptive’. What if we think of rubrics as describing what a native liturgy speaker would naturally do?

I’m drawing on Joseph Williams Style (Lessons in Clarity and Grace). He divides grammar rules into three kinds and accuses generations of grammarians, in their zeal to codify “good” English, of confusing three kinds of “rules”:

1. Real Rules

Real rules define what makes English English: ARTICLES must precede NOUNS: the book, not book the. Speakers born into English don’t think about these rules at all when they write, and they violate them only when tired or distracted.

So, I suggest that similarly, there are the first type of liturgical rules and rubrics that simply make these actions, signs, gestures, and words Christian liturgy. A leader who has been well formed in the Christian tradition does these (‘Real Rules’) things intuitively.

Joseph Williams has two other types of rules. The mistake is to regard all three as being identical in authority and importance. Grammarians make this mistake. Christians do so in liturgy and in discussing liturgy. We will get to these in due course.

Just as a good grammar book can help us to communicate with clarity and grace, so thinking through liturgy (and its rules and rubrics) helps us lead and celebrate worship with clarity and grace.

To be continued…

If you appreciated this post, remember to like the liturgy facebook page, use the RSS feed, and sign up for a not-very-often email, …

I’m looking forward to the continuation of this essay, Bosco!

I’ll be very interested to hear more about your analogy between liturgy and language, and to know what aspects of “liturgical grammar” correspond to Williams’s “Real Rules”. (This sounds like a very good style book. I’ve long been a “Strunk & White” man, myself.)

The advent of printing made widespread, immediate liturgical change at least theoretically possible. (For Anglicans, think of the repeated, legally enforced changes that took place between 1548 and 1553.) And now, with desktop publishing and projector screens — which still more recently have been able to draw on a limitless pool of electronic texts — the possibilities for repeated, instantaneous change are limitless.

I don’t deny that such changes can occur within the “rules” of a liturgical “grammar”. And perhaps ecumenical encounter and historical research can help us to determine what those rules are. But at times, the changes that have been introduced have struck at least some worshippers as fundamentally against the rules, in ways that would not have been possible in liturgical traditions that depended on memory and laboriously hand-copied books.

In my own parish, virtually the whole of every Sunday service is printed out in a folded leaflet, including the scripture readings. A few years before I became a parishioner, the then-rector was very concerned that the language of the liturgy should be inclusive. Among other things, she made her own “inclusive” versions of the NRSV readings in the RCL. Her successor discontinued this practice; but because the parish staff create the liturgy leaflets from existing computer files, these altered texts sometimes still pop up.

This happened a few weeks ago (Easter 5), when the Gospel was John 14:1-14. Every instance of the word “Father” in the passage was changed to “Creator.” We got to verse 7: “If you know me, you will know my Creator also.” I audibly gasped at the realization that I had just heard read in my own parish an alteration of the Bible that turned Jesus’ relationship to the Father into that of a creature to its creator. (My five-year-old asked, loudly, “What happened, Daddy”) But nobody else batted an eye. Not even the highly educated priest who was reading the Gospel (from a laser-printed sheet in a brass binder).

I ask: Can such a congregation be trusted to “speak” any sort of authentically Christian liturgical language?

There’s a lot in your comment, thanks, Jesse, not least the increasing abandonment (here, at least) of repetition (and memory). I have a projector-screen post in mind. Blessings.

You make me remember one of my former seminary colleagues who has eventually become priest, and vested himself on Easter morning with 4 chasubles… because the book said: «all the garments of white color.»

I use to think like you, that most of us understand things without them being written. Even the music signs in the beginning were used only to help the cantor throughout a KNOWN tune. But there are many people who cannot do without the rubrics of 1st class (real rules)… And that’s sad.