I appreciated recent discussion online around this website in relation to Original Sin and especially the Western mistranslation of Romans 5:12.

Romans 5:12 reads:

Διὰ τοῦτο ὥσπερ δι’ ἑνὸς ἀνθρώπου ἡ ἁμαρτία εἰς τὸν κόσμον εἰσῆλθεν καὶ διὰ τῆς ἁμαρτίας ὁ θάνατος, καὶ οὕτως εἰς πάντας ἀνθρώπους ὁ θάνατος διῆλθεν, ἐφ’ ᾧ πάντες ἥμαρτον

Therefore, just as sin came into the world through one man, and death came through sin, and so death spread to all because all have sinned— (NRSVue)

We refer to the translations of the scriptures into Latin, made in the early centuries of church history, as Vetus Latina. Jerome (in the late 4th Century) revised a lot of Vetus Latina. Romans 5:12 was translated as

Propterea sicut per unum hominem peccatum in hunc mundum intravit, et per peccatum mors, et ita in omnes homines mors pertransiit, in quo omnes peccaverunt (Vetus Latina)

propterea sicut per unum hominem in hunc mundum peccatum intravit et per peccatum mors et ita in omnes homines mors pertransiit in quo omnes peccaverunt (Vulgate)

Wherefore as by one man sin entered into this world and by sin death: and so death passed upon all men, in whom all have sinned. (Douay-Rheim)

A key difference between the Greek and the Latin is that the Latin has “in whom [Adam] all have sinned”. The Greek does not. Before continuing, it is worth noting:

the Vulgate became the standard Latin Bible used by the Catholic Church, especially after the Council of Trent (1545–1563) affirmed the Vulgate translation as authoritative for the text of Catholic Bibles. However, the Vetus Latina texts survive in some parts of the liturgy (e.g., the Pater Noster).

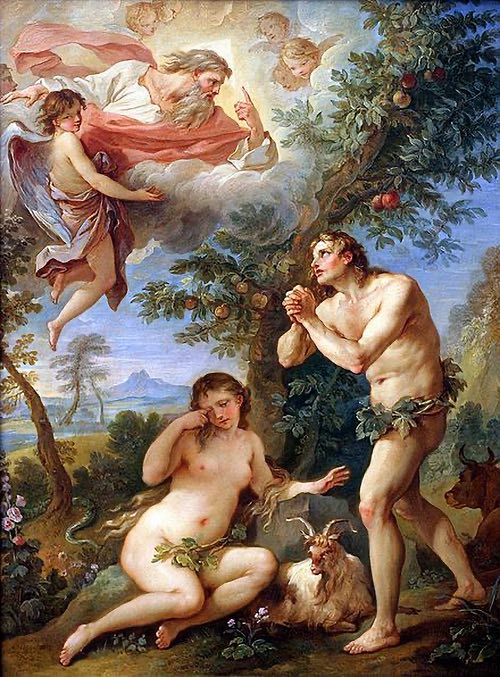

Augustine, and Western Christianity following Augustine, holds that “All people have sinned in Adam”. All people inherit the guilt of Adam’s sin. The Catechism of the Catholic Church teaches:

How did the sin of Adam become the sin of all his descendants? the whole human race is in Adam “as one body of one man”.

By this “unity of the human race” all men are implicated in Adam’s sin, as all are implicated in Christ’s justice. Still, the transmission of original sin is a mystery that we cannot fully understand. But we do know by Revelation that Adam had received original holiness and justice not for himself alone, but for all human nature. By yielding to the tempter, Adam and Eve committed a personal sin, but this sin affected the human nature that they would then transmit in a fallen state.

It is a sin which will be transmitted by propagation to all mankind, that is, by the transmission of a human nature deprived of original holiness and justice. and that is why original sin is called “sin” only in an analogical sense: it is a sin “contracted” and not “committed” – a state and not an act.

It is worth noting that, although the Catechism of the Catholic Church notes the Protestant Reformation in the debating of Original Sin, I cannot see there (let me know if there is, please) the difference that this Western view has with the Eastern view of Orthodoxy. Eastern Christianity has never taken on board this Latin mistranslation that all people have sinned in Adam, and that all people inherit the guilt of Adam’s sin.

There is an excellent discussion of the Greek and its translation into Latin here. Further good discussion is to be found here.

Both Martin Luther (1483–1546) and John Calvin (1509–1564) represent a radical Augustinian shift: equating concupiscence with original sin, maintaining that it destroyed free will and persisted after baptism. Luther asserted that humans inherit Adamic guilt and are in a state of sin from the moment of conception. …

Calvin developed a systematic theology of Augustinian Protestantism with reference to Augustine of Hippo’s notion of original sin. Calvin believed that humans inherit Adamic guilt and are in a state of sin from the moment of conception. This inherently sinful nature (the basis for the Reformed doctrine of “total depravity”) results in a complete alienation from God and the total inability of humans to achieve reconciliation with God based on their own abilities. Not only do individuals inherit a sinful nature due to Adam’s fall, but since he was the federal head and representative of the human race, all whom he represented inherit the guilt of his sin by imputation.

Anglicanism tends to follow this Western understanding of Original Sin [See Article 9], although Anglicans would generally not be disciplined for denying this Western understanding, or even denying the historicity of Adam and Eve and the literalness and historicity of the Genesis account of “The Fall”.

The Eastern half of Christianity, as I indicate above, does not follow the Latin mistranslation of Romans 5:12, but has reflected on the original, Greek text. For Eastern Christianity, there is not guilt transmitted to all from Adam. For Eastern Christianity, it is mortality that is transmitted. I regularly advocate for a more public acknowledgement by Christians of Science and evolution. Death is, obviously, integral to evolution. Death was present before humans evolved. If you want to pursue this from an Eastern Christian perspective, there are a number of resources provided here. Eastern Christianity would highlight that humanity is fallen but not totally depraved.

Do follow:

The Liturgy Facebook Page

The Liturgy Twitter Profile

The Liturgy Instagram

and/or sign up to a not-too-often email

Very helpful article. Re the Eastern view, which I also follow, I wouldn’t even say “mortality is transmitted.” In other words, I don’t think this is about transmission of anything (like some kind of fluid passed along, and again, How?) but a simple matter of consequence. Looking at the mythological portrayal: Adam lost access to the tree of life, and so lost immortality. Every other human since never had access to the tree. Nothing was transmitted because, this is about the loss of something. As one Eastern Father said, (I can’t recall who on the off hand): The West is concerned with the inherited guilt of Original Sin, the East with the consequences.

Thanks, Tobias – I think that’s an excellent clarification. Blessings.

What does it mean for Adam ‘to lose access to the Tree of Life’? What does it mean for a Christian understanding of life and death?

Is death natural to the human condition, part of the created order of things, the natural life (and death) cycle, as life everywhere on earth seems to show? Or is death *not* part of God’s original plan? Is death ‘God’s judgment on humankind for sin’, as one old and persistent Christian tradition has it (the orthodox western view)?

Is the Tree of Life, Christ? That which brings everything into creation, and enlightens them – presumably with a capacity for ‘eternal life’? So that we are created both mortal – out of the dust, dependent on God alone for our life breath, living in/as bodies that participate in the finite life cycle of all entropic matter, fated to die back into the nothingness out of which we were first created- *and* created with a capacity to participate more fully, grow more fully, into our primordial source, our nodal point with immortal life (“Christ”), our full human potential (“theosis”), though this has been subject to a tragic, cosmic “loss of access” (“sin”, “expulsion”)?

Thanks, Mark – I would be interested in Fr Tobias’ take on this. It underscores my regular contention that Christians need to do more work on reflecting theologically on evolution; or, if this is being done in whispering halls of academia somewhere, it needs to become widely available and accessible. Blessings.

I’ve just discovered Ilia Delio, who is refecting deeply on such matters, and to some extent channelling Teihard. It’s early days for me but she certainly is asking the right questions. There’s plenty on YouTube and my book club is about to do her new book “The Not Yet God”!

Thanks, Phil! What a great recommendation for exploration. Blessings.

Thanks, Mark, for these helpful thoughts. There is some tension between the tradition and the Scripture with regard to human mortality: the Scriptural “mythological” parable does not portray Adam and Eve as immortal by nature; in fact, I think it is rather explicit in that regard. But the Western church (a council in Carthage in 418, later reaffirmed by the Council of Trent) anathematized this view, alleging an original inherent or natural human immortality that was lost. I prefer the Eastern (and Scriptural) view that the only true immortal is God, and that human immortality was a derivative gift from God, a gift that could be lost, as indeed it was. This also, it seems to me, makes good sense of the restoration of immortality in Christ, through the “tree of the cross.” Our theosis involves the jointure of our human nature with the divine — a work already completed in Christ, and in which we participate by our union with Christ.

Thanks for your helpful reply Tobias. I am at the end of an introductory theology paper and was very confused by the notions of death and anthropology being promoted as the orthodox, catholic version: i.e. cicadas etc are subject to the natural cycle of life andvdeath, but not humans who were originally created deathless and then were made subject to death through God’s judgment on sin. That’s not the theology I picked up as child, and certainly not the one that makes sense to me, though it sounds like it has strong claims to being the classic, western, catholic position.

I do prefer the Eastern one to that, though the ‘coming of age’ version further below makes most sense to me (as a human, Christian, and psychotherapist).

Indeed the “coming of age” is a wonderful way to look at this; not only more at ease with reality (!) but also I think morally edifying. I wrote a long essay (or set of essays) on a kind of genealogy of morals that took this view some years back. If you’re interested, it’s at my now largely dormant blog: http://blog.tobiashaller.net/2008/05/good-as-gold-1.html

Thank you Tobias, I’ll definitely look it up!

Well, as one who denies historicity in Gen.1:-3: (and beyond), I’m glad there’s another way to read Rom.5:12.

Got me thinking though, it seems Paul is taking the idea of a Fall pretty literally in terms of it having consequences. And yet he was closer to the original texts than we are, temporally – critical textual analysis, the documentary hypothesis and friends are works of archæology these days. So… how long does it take for text to become scripture and “traditional” “understanding”s to take effect?

I’m with you, Tim, in not taking those early chapters as history or science. I would understand Paul as not understanding my previous sentence, or asking those kind of questions. Blessings.

This post and discussion has come at a great time for my next theology assignment, Bosco. I appreciate the thorough and broad-minded treatment you give to it, as with other topics you write on. Surprisingly, sadly, I find that that is rather rare these days. Can I ask you clarify your comment here on Paul….

Paul probably believes the Garden in Eden story to be literally true, to be history?

That’s great encouragement, thanks, Mark.

There are some who see Paul as a “literalist” – ie he thought, in contemporary terms, that the early chapters of Genesis were literal history. Others (eg. James Dunn – The Book of Romans) see Paul as not a literalist. I think both approaches are anachronistic. Prior to the scientific revolution, and its equivalent in our understanding of history, people happily mixed what we would now call science and history with what we would now call myth. We still find (many) people today who do not make the sharp binary distinction. My point was: if you hopped in a Time Machine and asked Paul, “do you think Genesis 1ff is science and history?” I don’t think he would understand the question. Does this make sense? Blessings.

That makes sense, Bosco, though a distinction between textual genres (e.g. prophetic literature versus wisdom literature)

must have existed. How did Paul regard Genesis? It doesn’t really matter, as we know how the Augustinian catholic tradition read this. The more important question (for me): how might we read this meaningfully (or not) now?

BTW, in terms of evolution and theology, a friend in the know recommends the following:

Christoher Sougthgate, The Groaning of Creation;

Celia Deane-Drummond, Christ and Evolution ;

John Haught, Deeper than Darwin

Nicola Hoggard (NZ theologian), Animal Suffering and The Problem of Evil;

New Zealand Christians in Science held a conference on the fall in science and theology last year – talks from that on their website nzcis.org

Thanks, especially for the references, Mark. I see the early chapters of Genesis form a couple of the (conflicting) origin stories. Your “or not” resonates with me. My position, which scandalises some, is that when we work out what an original author meant in a scriptural passage, we still have another step: does it apply now to my/our life, or not? For others, once the original author’s perspective is found, it must be followed/accepted. Blessings.

Another way of reading “original sin” is not as a destructive “fall” that invites wrathful judgement and that needs cosmic appeasement etc, but as a necessary coming of age that presents us with mature spiritual problems.

We can’t stay in the womb, in an immature Edenic union with our parents’ body and self, as much as some part of us would like that. We all eat of the ‘forbidden fruit’, develop a consciousness of self and other, right and wrong, separate from union with ‘the dynamic hground’ (Washburn), and enter the world of dualities. We grow up. We leave home. We face the often painful world of hard work, of pleasure (sex) becoming adult responsibility and sacrifice (as parents ourselves), and the painful knowledge of our mortality.

When my young son first found a dead bird he was heartbroken. He wanted me to take it to the hospital or do something to bring it to life again.

Adult life is inevitable and tragic – but also a state of spiritual incompleteness. We still long for union with God, our ‘dynamic ground’, but now must seek this as mature human beings. The Christian story is about Christ offering us a way.

A further thought came to mind as my mind was wandering last night: The notion of original mortality is also coherent with the Genesis 1 commandment to the primeval couple, “be fruitful and multiply.” I say this because progeny would not be needed if the couple were immortal; indeed, fertility and immortality would lead eventually to massive overpopulation. I base this view not on my own imagination, but on the teaching of Jesus in Luke 20:35-36, where he explains that those who attain the resurrection to eternal life do not marry, because they are immortal.

All of this seems to mesh with a notion that the primal fall lost something that the original humans had by grace, not innate nature; and that the effect of that loss falls on their heirs and assigns not as a substantial inheritance — the presence of an inherited sinfulness — but as the absence of something. If you think of it as something an ancestor had and then lost — say, a deed to a silver mine — it is easier to understand the current poverty of the heirs is due not to something passed along, but precisely to something not passed along.

Quite. In dying we make space for the new, for the next generation coming along. This seems true both ‘actually’ (so the world isn’t chronically overpopulated, so I’m not clinging onto work and leadership positions that young people should now be filling), as well as symbolically (rebirth of the true self in Christ requiring us to undergo the death of the ego-self etc). It emphasizes the logic of the ‘coming of age’ version of the Eden story, too; Adam and Eve needed to leave the Garden for humanity and history to begin. Of adulthood as inevitable, costly, tragic, involving significant loss, but also immensely creative and joyful (the arrival of new life).

Love the ‘deed to the silver mine image, Tobias, yet I struggle to accept any literalism here. It can’t believe that we were once actually immortal *in this world*. For me the silver mine would be the openness to the eternal within and around us that we perceive more clearly in childhood, often.

Death as *transitus*:

“Today marks one of the most solemn feasts in the Franciscan calendar: the Transitus of St. Francis of Assisi. It is a commemoration of his death on the evening of Oct. 3, 1226, and it is a time when the Franciscan family gathers to mark not just his death, but also his passage to new life in Christ. The Latin word transitus is significant because it reflects Francis’ belief that death was not an enemy nor was it an end. Instead, Francis believed that bodily death was part of God’s plan for creation and not something to be feared; he even called death his “Sister.” Using transitus to refer to death denotes a transitional or liminal moment between two forms of life, a continuation of what has begun in this earthly life is now carried on into the mystery of the next life.”

https://www.ncronline.org/node/283666