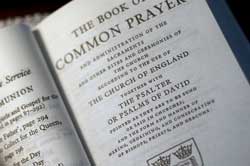

This year is the 350th anniversary year of the 1662 Book of Common Prayer. The Secretary-General of the Anglican Communion, Canon Kenneth Kearon, preaching earlier this month in Dublin’s Christ Church Cathedral, on this topic, made some good points:

This year is the 350th anniversary year of the 1662 Book of Common Prayer. The Secretary-General of the Anglican Communion, Canon Kenneth Kearon, preaching earlier this month in Dublin’s Christ Church Cathedral, on this topic, made some good points:

“Central to these reforms [the Church seeking to preserve much of its ancient order, while also adopting many of the new religious ideas and concepts from continental Europe] would be a common prayer book for all the people, expressed in the vernacular. While a noble ideal, the task proved to be far more difficult. Many versions and editions were put forward with varying degrees of success—most notably the prayer books of 1549 and 1552—but it was not until 1662 that a Book of Common Prayer emerged which met the needs and caught the imagination of those who sought to express the new reformed faith in a widely acceptable form of worship.”

“The Book of Common Prayer didn’t seek compromise between opposing positions; instead, it sought to include very diverse positions into one liturgical rite. The Book is profoundly inclusive,”

“In its theology, it outlines a method which is profoundly inclusive; as liturgy, it gives substance to the integration of worship and teaching lex orandi, lex credendi (‘the language of worship is the language of belief’); and the way it uses words leads the worshipper into realms of religious imagination which are ultimately inexpressible.”

Interestingly, as Secretary-General of the Communion, he claimed that nowhere in the Communion do Anglican Churches regard liturgical revisions as formularies. That is, of course, quite incorrect. In the Anglican Church in Aotearoa, New Zealand and Polynesia our prayer book A New Zealand Prayer Book/He Karakia Mihinare o Aotearo is certainly enshrined in our Constitution as a formulary of our Church.

In this post I also want to highlight some comments of Steve Benjamin, a regular here:

During a period of ecclesial abandonment, the BCP 1662 became a portable church for me and sustained me in the faith in a period of exile.

The Daily Offices kept me nourished by the Word of God. I learnt that the BCP pattern was more important than the full content and discovered the various time-hallowed ways of abbreviating, shortening and combining the services without violating basic rules of liturgical order.

On Red Letter Days and Sundays I kept in sync with the liturgical year by celebrating the Service of Ante-communion (aka a ‘Dry Mass’ or the Lord’s Supper up to when a priest is absolutely necessary, ie the end of the Prayer for the Church Militant).

I learnt that Mattins, Litany and Ante-communion had been the staple of C of E worship on Sunday morning for centuries and could be a worthwhile way of keeping the Lord’s Day if one was prepared to put in the time and effort.

I even celebrated the Service of Commination on Ash Wednesday and enjoyed its fire and brimstone Exhortation with the added frisson of knowing, that like most robust expressions of faith, it had been banned from public celebration, at least in the Anglican Church of Or.

I started to welcome second-hand BCP’s into my liturgical retirement village and would carry a pocket BCP around with me like a talisman. Whenever I was in a waiting-room or queue I’d turn to the Psalms (how good is Coverdale’s translation? – 477 years old and still gracious in rhythm and cadence) or read the Sunday Collect, Epistle and Gospel. No other book has been printed in such portable versions with such legible print and good binding.

Anglicans do well to remember that, other than our Saviour, we have no founding personality who looms large over our tradition, nor a charismatic figure leaving his or her mark on our ecclesial community. We have a public prayer book: a comprehensive liturgical text which has shaped and structured our hearing of God’s Word and celebration of the Sacraments for over 400 years.

In its short compass we go from Advent Sunday to All Saints’ Day, from birth to death, from the apostolic ministry to the principles of reformed theology, from curious almanacs to work out the most pivotal date of the Christian year to a lectionary of readings conveniently linked to the calendar month. All in a book which is 75% derived from Scripture and retains Cranmer’s matchless translations of those liturgical haikus of the Western church: the collects.

In this commemorative year I hope to participate in a full BCP Mattins as I have yet to experience this service. I wonder if I might also hear the BCP Litany as this would also be a first. I’m resigned to being born 100 years too late to experience the full force of the Commination Service in a congregational setting – liturgy at its most hard-core!

With regard to the flexible use of the BCP, I have no sites as references as I was thinking of the various approaches towards simplifying the BCP (especially the Daily Offices), found chiefly in books for popular devotion such as the pre-Puritan English Primers and Bishop Cosin’s Book of Hours of Prayer.

Proctor and Frere in A New History of the BCP (1929 edition, pg 223) refers to the custom of ‘Short Morning Prayers’ in the 17th century being celebrated in churches at an early hour. Popular twentieth century office books (often for church school use) provided Shortened Mattins and Evensong orders which after the opening versicles and responses, provide a simple structure of a single psalm or psalm portion, one Lesson, a single canticle, Apostles’ Creed, Lesser Litany, Lord’s Prayer, Preces and collect(s). This is very similar to how the Church of England restructured its Daily Office in its Alternative Service Book 1980.

The extremely popular green Shorter Prayer Book incorporated many features of the 1928 BCP but also gave outlines of how to combine Mattins with Holy Communion (conclude Mattins after the second canticle and begin the Communion Office, pg 12); how to simplify the Litany (omit some of the suffrages ad libitum and omit the entire Supplication, pg 29); and how to use a form of the Litany as a preparation for Holy Communion, pg 29.

These approaches and the desire for flexibility eventually resulted in the so-called Shortened Services Act of 1872 (or The Act of Uniformity Amendment Act). The way the legislation envisaged the simplification of the BCP violated many liturgical norms but it gave legal authority to reshape the BCP orders when pastorally appropriate and has had long lasting effects despite some of its dubious directions (eg the omission of the integral second Lord’s Prayer at Mattins or Evensong).

In this 350th anniversary year of the BCP, it’s worth noting how the Shortened Services Act in 1872 unbound the strictures of BCP worship and gave room for a form of liturgical innovation. New non-eucharistic services could be compiled for the first time as long as their contents derived from the Bible and the BCP. The Act of Uniformity was giving way to the freedom of the Spirit – in an Anglican sort of a way.

Thank you Steve, and the many others in our community here who continue to enrich and challenge certainly me, at least, and I am sure many, many others.

I came to your blog from the church relevant site top 200 list. They have created a tremendous forum for finding new blogs that impact people.

I hope my blog can be an encouragement to you also.

I write it for encouragement and motivation daily.

http://i-never-fail.blogspot.com

Thanks for sharing. Looking forward to watching the connections grow!

Thanks for pointing to the Church relevant site, Craig. I see there that this site is number 66 of “the world’s most popular church blogs written by many of today’s most influential church leaders, journalists, theologians, and Christ followers.” Wow – that’s possibly worth a blog-post in itself! I’ve enjoyed visiting your site – certainly encouraging. God bless your online mission and ministry. It’s hard work, has some stresses, and is very worthwhile. Blessings.

Thanks for your kind words and for stopping in!

Congratulations on reaching 66.

Though not a Christian, I am able to understand hard work and understanding.

I wish you continued success and understanding

Thanks, Keith, for your visit and comment. I hope that people of all faiths and none understand they are welcome here. Blessings.

I love Steve’s comments on the BCP. Interestingly though not widely recognised as fact, the start of the rapid decline in church attendance in England following the glory days of the 1950’s co-incided (some might suggest suprisingly) with the C of E starting experimenting with other more ‘relevant forms’. I myself as a chorister have memories of a constant round of liturgical discontinuity which I imagine to worshippers of more mature years must have been extremely disorientating.

In brief response to what Steve has written – we still have BCP Evensong monthly here at St John’s Roslyn and his comment about Matins sparked a thought regarding a proper marking of this anniversary… For the last ten years of my ministry in England we had full prayer book matins (1662) once a month. I miss it and a celebratory Matins is perhaps in order!!

As to Coverdale’s Psalms and Cranmers collects – I look to them to transport me through the years of failing faculties, deeply embedded as they are (and I haven’t yet turned 50! 🙂 )

Thanks for your posts on the BCP, Bosco. This anniversary will probably not be as widely marked or as with as much hooplah, as last years for the AV yet I think in terms of church history is of fundamentally more significance.

Pax et Bonum

Bosco, I am truly honoured that the personal witness to role of the Book of Common Prayer in my spiritual development has been quoted on your revered site. I’d like to add that I have now reconciled myself to 20th and 21th century liturgical use but am ever mindful of our origins.

On reading the main points of Dr Kearon’s address, I sense a strong disconnect and can only assume that the chapters on the 1661 Savoy Conference were missing from the histories of the Book of Common Prayer which he consulted to prepare his address!

Rather than being a celebration of inclusiveness the revision of 1662 set up legitimate boundaries: it restored liturgical order after the ‘anarchy’ of the Cromwellian regime and was the direct result of resurgent episcopal governance in the Church of England. Over 2000 ministers were ejected from their benefices because they refused to accept the 1662 revision and the requirement of episcopal ordination, if that was lacking (The New History of the Book of Common Prayer, Proctor and Frere, pg 201, 1929 edition).

The Savoy Conference deliberations make interesting reading. If you want to understand what liturgical order means as opposed to ministerial freedom to construct worship ad libitum, you find it laid out in full in the Presbyterian objections and the sage replies from the Bishops.

As Proctor and Frere note:

The Bishops rejected [the objections of the Puritans], as they explained in the new Preface [to the 1662 Book of Common Prayer], on the ground that they ‘were either of dangerous consequence (as secretly striking at some established Doctrine or laudable Practice of the Church of England or indeed of the whole Catholic Church of Christ), or else of no consequence at all, but utterly frivolous and vain.’ (Proctor and Frere, pg 199-200).

The Bishops had witnessed civil war, regicide and the judicial murder of the Archbishop of Canterbury. Under the Cromwellian regime they had suffered ejection from their sees and the subversion of ecclesiastical order as they understood it. The use of the 1604 Book of Common Prayer was outlawed by the Cromwellian parliament, even in private. Their antipathy for the Presbyterian system and its practices is perfectly understandable.

The 1662 revision marked the end of the Church of England project to offer a comprehensive liturgy for the entire English nation. This was no longer possible as the divide between those holding to both episcopacy and the liturgical principle and those holding to Presbyterianism and ‘free worship’ had grown too wide. This meant the parting of the ways for ‘Churchmen’ and Independents/Presbyterians in England. The Church of England, restored and re-established by law, declared firmly: bishops and liturgy are not negotiable.

Additionally, the 1662 revision provided the authorized liturgy for the British Empire at prayer and, in keeping with Article 24 of the Articles of Religion, was translated into other languages so that worship could be conducted in ‘a tongue…understanded of the people’: French in the Channel Islands, Greek and Latin for those at Oxbridge, and over 100 different languages – including, of course, Te Reo Maori – for those who would encounter the proclamation of the Gospel by Church of England missionaries. (Proctor and Frere, pg 203).

PS: Thank you, Eric! I’m very glad to hear the idea of Festal Mattins is taking off! I gather no plans for the Commination Service?

Thanks, Steve. I wonder if, in this anniversary year, our province might hear what the Spirit is saying to the Church through what we call a formulary of our church. Blessings.

Dear Rev. Bosco Peters,

The Book of Common Prayer used by the Church of England is slightly different from the Book of Common Prayer used by the Church of Ireland. There is different collects on Good Friday and also Morning Prayer in the Church of Ireland also has the Canticle, Urbs Fortitudinus, Isa.26:1.

It is all by the grace of God.

Frank.

Thanks, Frank. Could you give the date for the BCP (Ireland) that you are referring to please? Blessings.

Dear Rev. Bosco Peters,

The Church of Ireland BCP is the 1926 edition. The University Press of Oxford have published it in times past.

There is also the 2004 Church of Ireland BCP published by Columba Press does not have the Psalter used in the BCP, instead it has the Common Worship version.

Primarily I am referring to the 1926 edition of the Church of Ireland BCP.

Kind regards,

Frank.

Thanks, Frank. Yes, every Anglican province has its own Prayer Book, either titled “BCP” (eg Ireland, as you say, TEC,…) or not (eg NZ). Blessings.