I was with a group of clergy recently where I mentioned the idea of changing the configuration of seating for different seasons of the Church Year, for example:

- semicircle around the altar for one season;

- straight lines facing each other in “choir formation”, altar at one end, ambo/lectern at the other (or similar to this but with the lines of seating curved) for another season;

- “traditional” cinema style, straight lines facing the front;

- choir formation by the ambo/lectern for the Liturgy of the Word, altar by itself – all gather standing around it for the Liturgy of the Sacrament (as you come in, you either meet the seating, or the altar is by the entrance door);

- …

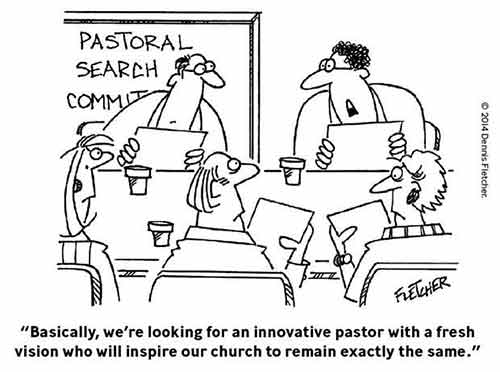

The reaction? One very strong one: “That would mean moving or removing the pews”. Yes. “That would be the start of war.”

There are some positive things we can learn from this insight. We regularly think that it is the words that are important (and, of course, they have some importance). But, actually, it is clear that we are deeply affected by architecture, by the physical objects and their arrangements. Positively, then, it highlights how important these things actually are to us. Physical things, and their arrangements, are sacramental, transformative.

More than focusing solely on the words, and reducing liturgy to didactic pretty poetry recitals (with some of the poetry set to music), actually architecture, actions, and the arrangement of the community (which need not be invariable) are some of the deeper elements of liturgy – and can affect us (and transform us) deeply.

What interests me when I hear of these moments is that we’re meeting the entrenched and unconscious mindset that clergy and laity of another era created and passed on. Moving things around seasonally seems to me a move that some of our colleagues discovered as a way to get people to try something. But the sacred cow is hidden in the list and thank you for the quotation marks around its description – “traditional” cinema style, straight lines facing the front. So far as I can tell this is the legacy of Christopher Wren’s brilliant and liturgically appropriate rebuilding of London’s 17th century churches after the Great Fire. It looks to me like he observed the liturgy of his day where an extended, rhetorically and intellectually elegant sermon was the Big Event and built his new churches as “auditoriums,” places for listening to a teacher or leader in authority. The new churches ignored how people had gathered for common prayer, ignored what it takes to make us more attentive to one another’s offering of prayer, ignored what helps us sing together, ignored how we might be humanly inclined to sit if we were simply be present to God and one another in silence. Given what Anglican liturgy looked like in 1666 after Cromwell, Wren was making a good architectural choice. But as we seek to recover ways of genuinely common praying, the power of participation and presence to one another in Christian formation, and a theology of Christ present not only “up there” “on the altar” but among us as well, we have good reason to ask one another (laity and clergy) what the actual tradition of the last two thousand years offers us of ways people have gathered to pray. I think the difficult but essential first conversation is about what we’re doing together. And from there we might venture into asking how we gather and shape the assembly to do that. The other options you attempted to discuss with people are (as you know, of course) very traditional. And I think the question we’ve got to help people consider is why these traditional configurations were used and what happens for us in each of them.

Amen, Donald. Blessings.

As my liturgy professor (James Farwell) said, te space always wins.

In seminary we ha the luxury of two very different but flexible worship spaces which were arranged differently at regular intervals. It was amazing how space could transform an otherwise I changing liturgical form. Alas, not so easy to implement in the parish after all.

Our rector emeritus visited to preach one Sunday, as we are about half-way thru an interregnum. He was the rector during the construction of our church building. My, he started a furor when, during his homily, he offered the suggestion that “moving the altar,” or more accurately, “making the altar movable” might be a good idea. Our interim has been pondering starting that conversation, which obviously won’t come to any conclusion during his stint. I’ve suggested we not, yet. But I have been thinking about “altar” vs. “table” and how different the symbolic meanings are between a wood table, not totally unlike my own dining room table, and a concrete slab on concrete legs, immobile and nothing at all like my own place for eating.

Our church, like many if not most, has a fixed arrangement. Pews are bolted down, the altar weighs a ton (perhaps literally), the ambo and pulpit are fixed (also concrete). It is a lovely space, semi-round with open beam pine ceiling, and I fell in love with the place the moment I first stepped through the doors. But, it is, quite intentionally, fixed and unchanging. And I wonder about the wisdom of that.

I had a wonderful liturgical experience in Philadelphia in a church arranged in choir (seats facing each other), with a meditation pool / baptism pool in the middle, and ambo on one side. The arrangement lent a strong feeling of intimacy. The congregation processed (well, ambled over) to the Table and stood in a circle around it during the Holy Communion. Terrific space for fifty or sixty participants.

I was a member of a (Methodist) church for 3 years, where the minister instituted a 6months of trad seating followed by 6 months in the round, with the altar table in the centre. I was always taken aback at the start of each 6 months, and by the end of the first month, wondered why I had minded. Each time. It was really useful.

I know of a church that did exactly that, for many years, with chairs. Almost universally, the congregation hated it passionately, and it never grew on anyone. It was disliked to the extent that it obscured worship because were so fed up with the physical conditions.