The Book of Common Prayer (1662) says, “And the Priest standing at the north side of the Table shall say the Lord’s Prayer, with the Collect following, the people kneeling.”

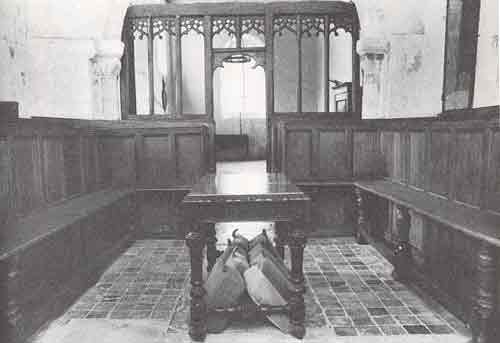

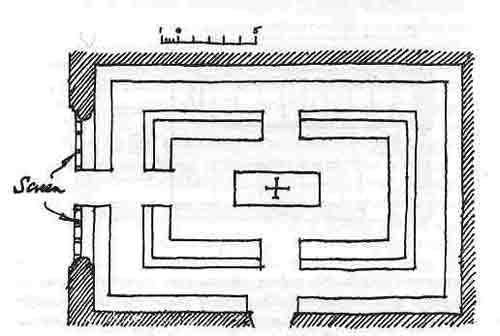

This is a photo prior to 1960 in Hailes church in Gloucestershire. It clearly illustrates how the altar table was put lengthwise between the choir stalls in the chancel. The priest stood on the north side of this table in the midst of the people:

As it is today looking West.

The eastern end of this church has been altered now. The eastern seating has been removed and there are steps and a freestanding altar of the medieval configuration.

On holiday recently, I popped into an open church (as one does) to find an altar still against the east wall and bookstand and kneeler clearly set up for presiding from the north, narrow side of the altar.

When there are two at the altar, one on either side, this is sometimes referred to as the “ping pong” position. I have also heard it called “the kangaroo and the emu“. I have even seen this 1662 rubric “translated” into the situation where the priest presides across the altar table facing the congregation: the priest stood not in the centre of the altar, but on the north side behind it… “leaving a gap in the middle for Jesus who is the one actually leading”.

[Needless to say, for those not regular visitors here, my describing of these unusual clerical approaches is in no way to be read as supporting them!]

Offsite discussion about north-side presiding

Well. Bosco, if the late Dom Gregory Dix, O.S.B., was able to speak of the Eucharist celebrated in very different places and ways in an emergency (such as, e.g., on the bonnet of a car during war-time), I suppose the Lord would still come to the Celebration – that is, if His Presence is really expected. What is important is the focus of the Celebration. Is it Christ, or the ‘minister’?

Agreed, thanks Fr Ron.

The BCP envisioned the wooden Holy Table (not an altar, BTW) being a portable object, probably on trestles, which the congregation would kneel around, in a circle. It was Laud who undid all that by ordering a fixed piece of furniture fenced off and against the east wall. Those who followed the rubrics post-1662 were stuck with Laud’s changes, hence the ‘ping pong’ position. No Anglican was going to lead communion with his back to the congregation.

The communion table that is wheeled into St Andrew’s Cathedral in Sydney actually captures part of Archbishop Cranmer’s intention.

Thanks, Steve. In November 1633 it was an act of the Privy Council under King Charles I that ordered parish churches to follow what had become the general practice in cathedrals of putting the tables back in the east end. Latticed altar rails were put there to protect the altar against desecration. In Laud’s words: “the altar is the greatest place of God’s residence upon earth, greater than the pulpit for there ’tis Hoc est corpus meum, This is my body; but in the other it is at most but Hoc est verbum meum, This is my word.” In the Civil War BCPs and surplices were torn up, communion tables were relocated, and altar rails were burned. The Restoration and 1662 revision of BCP made no alterations. Clergy continued to move among the people to distribute communion until the eighteenth century when the altar rail came to be used as the communion rail. Blessings.

, by act of Privy Council King Charles I established the precedent that all parochial churches should follow the by then general cathedral practice of placing communion tables altar-wise at the east end of chancels.

Thanks, Bosco. Cranmer’s reforms had removed the fixed stone altars from churches and replaced them with portable wooden tables, to teach the reformed doctrine that this was a communion meal (‘the Lord’s Supper’) rather than the sacrifice of the mass. However, the table was not kept “holy” but used for all kinds of “profane” purposes, hence the actions of the high churchman Laud – whose brutal treatment of the Puritan Prynne and others, and other acts on behalf of Charles would cost him his life when Parliament was finally called in 1641.

I’m not sure what sort of “profane” purposes you suggest that Cranmer envisioned using what he called “Goddes borde” for?

Cranmer didn’t envision “profane” purposes for the table; but in the Caroline period there were complaints that in some places the table was being used for writing out parish acounts, or men would place their hats there etc.

I can’t access the pictures in this article. Can you help? Thanks.

Thanks for highlighting the issue, John. Some WordPress upgrades appear to have removed some images in different posts. I have fixed this now. Blessings.

You are welcome. Glad to help. Thanks for fixing! Blessings!