This is the fifth in a series attempting to nuance the statement, “The Bible says…” I encourage you to read the story so far:

Textual Criticism

The Septuagint (LXX)

Hebrew vowel pointing

The canon

There’s also been a related post, “the pope says…”

Translation

What do you call someone who speaks three languages? Trilingual

What do you call someone who speaks two languages? Bilingual

What do you call someone who speaks one language? …..

…English (or American, or a Kiwi,…)

People who have no agility in more than one language regularly misunderstand what is involved in translation. Concepts, tenses, constructions may exist in one language with nothing comparable in another language we are trying to translate into. Hebrew tenses can only be approximated into English. Greek is a highly inflected language, so that the function of a word is modified to indicate information that cannot easily be simply translated into English where word order is far more significant. Word order in Greek can be significant in stressing and highlighting. We struggle to be sure what some of the words in Hebrew or Greek even actually mean – even after we have determined which word was there in the first place.

A specific problem in translating is that there are some words that occur only once in the Bible and nowhere else in ancient literature. Such a word is called a hapax legomenon. The meaning of such a word can be particularly obscure, with guesses made from the context.

Muslims regard every translation of the Qur’an from Arabic as being a commentary. That would be a helpful starting point for those who refer to an English translation when they say, “The Bible says…” Actually, “this particular English translation says… this particular interpretation… this particular English commentary on the original…”

There are different ways to translate. Generally these different translation approaches can be categorised as:

Formal equivalence: the attempt to translate word for word, trying normally to translate the same word in the original consistently into the same word in the translation, and then attempting to disrupt the word order as little as possible in the English translation from the word order in the original.

Dynamic equivalence: the attempt to translate idea for idea, without attention to consistent word translation or original word order.

Paraphrase: the attempt to restate the content in language easy for the contemporary English reader to grasp.

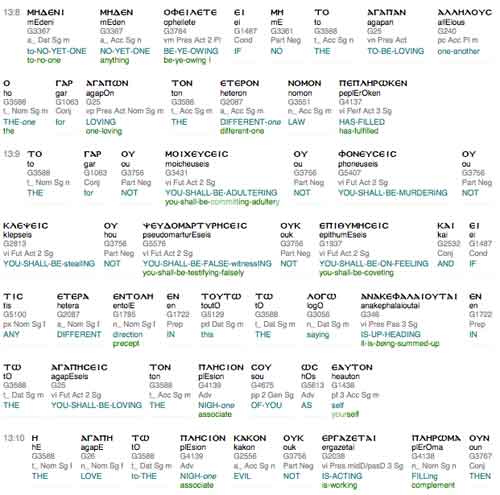

Maybe an example from this coming Sunday’s reading helps. The original of Romans 13:8-10 reads:

The above is from the Greek interlinear text

A formal equivalence translation (NRSV):

8Owe no one anything, except to love one another; for the one who loves another has fulfilled the law. 9The commandments, “You shall not commit adultery; You shall not murder; You shall not steal; You shall not covet”; and any other commandment, are summed up in this word, “Love your neighbor as yourself.” 10Love does no wrong to a neighbour; therefore, love is the fulfilling of the law.

A dynamic equivalence translation (CEV):

8Let love be your only debt! If you love others, you have done all that the Law demands. 9In the Law there are many commands, such as, “Be faithful in marriage. Do not murder. Do not steal. Do not want what belongs to others.” But all of these are summed up in the command that says, “Love others as much as you love yourself.” 10No one who loves others will harm them. So love is all that the Law demands.

A paraphrase (The Message):

8-10Don’t run up debts, except for the huge debt of love you owe each other. When you love others, you complete what the law has been after all along. The law code—don’t sleep with another person’s spouse, don’t take someone’s life, don’t take what isn’t yours, don’t always be wanting what you don’t have, and any other “don’t” you can think of—finally adds up to this: Love other people as well as you do yourself. You can’t go wrong when you love others. When you add up everything in the law code, the sum total is love.

I have (purposely) chosen a text that is pretty uncontroversial. If I chose a text with a variety of complex interpretations, we could get distracted from the primary point of this particular post onto debating the various interpretations.

What I hope is clear is that these three categories of translation are not discrete, but rather, that there is a spectrum of translation approaches with the more formal equivalent at one end and paraphrases at the other. Every translation involves interpretation by the translator. When someone says, “The Bible says…” and then continues with an English translation, we need to understand the issues around such a statement…

You are right, Bosco! There is only one logically consistent usage in English of ‘The Bible says’ and that is when ‘The Bible’ = ‘The Authorised Version’ 🙂

Bosco, fantastic post as ever.

Although I must feel I disagree to an extent.

To say that translations can only ever be commentaries, means that if Christians are to be a People of The Book, then we can only ever be People of A-Dead Book, which is something I am loathe to admit.

Perhaps I have misunderstood.

But surely the Anglican tradition is that we can be assured of your Biblical translations so long as we translate in accordance with oecumenical councils, the creeds, and other such bits and bobs. For you see, it is the spirit of the words that is sacred, not the text itself, which is why I think your analogy with the Koran is flawed.

As an aside, I do hope Mr Carrell is joking.

Thanks for the encouragement, Mark. Whether “Christians are to be a People of The Book” is a fascinating discussion, looking at some of the issues arising from this series from a related angle. Certainly, circular though that discussion would be, “Christians are to be a People of The Book” is not stated as such in The Book. Some may, of course, derive this from The Book.

I am not convinced by your suggestion that our Biblical translations be filtered through the lenses of “oecumenical councils, the creeds, and other such bits and bobs”. Thanks for kicking off a discussion.

I have just recorded a BBC programme on this subject – discussing the idea of sacred text and translation with 2 other scholars – one a Sikh, one a Muslim. It’s an endlessly fascinating discussion.

Thanks for your thoughts, Bosco.

Maggi, do you have the title of this programme so I can find it online? Or give any other information about watching it?

Great post. It’s funny how I found I preferred the dynamic equivalence translation, much more poetic. It also was the most concise.

Thanks for the helpful comments and discussions.

Cameron, the word “paraphrase” can also be used for a translation.

Mark, I am presuming the importance, value, and centrality of the scriptures in our Christian life. Poke around this site a bit, and anyone will see its significance and centrality in my life and the life of the Christian community. Like all things of great power, using it well brings great benefit.

Nice article!

One (possible) quibble though: is it accurate to call the Message a paraphrase? My understanding is that a paraphrase restates a passage (or book) in the same language, whilst a translation changes the language. And as I understand it, Eugene Peterson worked from the Greek and Hebrew. This would make it a translation.

This contrasts with the Living Bible, which was cast from an English translation.

Bosco, you are quite right in saying ” “Christians are to be a People of The Book” is not stated as such in The Book”; a point (and its logical conclusions I spend a lot of time pointing out to my fundie friends).

But, between us at least, surely as we Anglicans do not artificially remove the Bible from its place within catholic tradition – we can see that early Christians strove for Christianity to be a written down religion? Firstly, their reverance for the Jewish scriptures, and the fact that early liturgies included the reading -and repetition- of early “canonical” letters.

The Christian tradition is one where again and again the Bible is placed atop of our theology. Surely to lessen this is to deny the very tradition that made it so?

I was forced to step down my rhetoric recently though, a good Angocatholic made me see the circularity of some of my reasoning (re the authority of Scripture), but I believe I made him stop and think when I nuanced my argument by suggesting that the Scriptures should be regarded as a form of Constitution. (bearing in mind I live under the English constitution) what are your thoughts?

Fantastic work…this should be posted far and wide!! Good for Bible study classes of all denominations.

I suppose it would be quite postmodern of us to say that “within the Bible there is a deposit of absolute truth – however, we as mere mortals can only gaze into the waters of scripture to see it refracted through language”.

I would suggest that before we even translate a text, something is lost between the writing down and the reading. No-one can cone to a text without presumptions, culture, predjudice, etc. So even if we all spoke Greek, well, as Blake said:

“Both search the scriptures day and night, one sees black, the other white”.

NB Love the site, some really useful / inspirational / challenging stuff… Keep it up!

Thanks for the encouragement, Mark.

A super post! Very helpful and informative as ever.

Hapax legomenon, a lovely phrase: reminding me of university Greek class: “pay careful attention to this word (or verb form), because you will never see it again”.

Thank you for all your work, another thing I can be thankful for in this northern (USA) season.

Thanks for your encouragement, Judith. I love your Greek class story.

Great post!