A couple of days ago I asked the question in relation to Sunday’s readings: Does the gospel really imply that nagging God works?

I just want to briefly spend time with part of the readings, Luke 11:5-8. I translate this, pretty literally, but trying to keep some English sense:

5 And he said to them, “Who among you (Τίς ἐξ ὑμῶν) will have a friend, and come to him at midnight and say to him, ‘Friend, lend me three loaves (of bread)

6 because a friend of mine has arrived from a journey to me, and I do not have anything that I will set before him.’

7 And that one within, having answered, may say, ‘Do not cause me troubles; already the door has been shut and my children are with me in the bed; I am not able to get up and give you (anything).’

8 I say to you, even if he will not give to him, having arisen, because he is a friend of him, yet because of the shamelessness of him (ἀναίδειαν αὐτοῦ), having arisen, he will give to him as much as he needs.

Τίς ἐξ ὑμῶν is used to mean, “imagine the unthinkable” (cf Luke 12:25; 14:5, 28; 15:4; 17:7). Then the story is set in a Middle Eastern/Mediterranean village, an unexpected person arrives, and the mores of hospitality means that this person will be provided with good food, the best, and more than the person would require. I have experienced this personally.

The story presumes the host either does not have good enough, or quantity enough, or both. The person turns to a friend. Key words in what follows are “ἀναίδειαν αὐτοῦ”.

ἀναίδειαν means “shamelessness” or “impudence” in the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, all classical references, and all usages in the early church. A “negative” word. But it has often been translated, incorrectly (IMO), as “persistence”. There is, you will have noticed, no actual persistence in the parable, the friend outside only asks once. Shame is a central motivator in this culture.

αὐτοῦ (of him). It is not clear to whom this refers. (a) Is the shamelessness a reference to the friend indoors? A positive use of “shamelessness” where the one indoors is avoiding dishonour. (b) Is the shamelessness referring to the friend outdoors asking? In the usual negative sense.

First century peasants lived precariously, hand to mouth. Here we have a story where the village looks to be in a hazardous economic situation that the original hearers would immediately identify. The person has gone beyond asking kin for help, to friends. And hospitality is foolishly extravagant, resulting in great vulnerability. This is the kind of generous hospitality acted out in the meals of Jesus, and ultimately in his death (also recalled/relived in a meal).

This parable of three friends reads a bit clumsily, even in the Greek – friendship in that context and in ours is possibly a wonderful image to explore in our relationship with God as a metaphor alongside father in this gospel reading.

This site offers a good variety of tools to access the original texts even for those with limited to no original language skills.

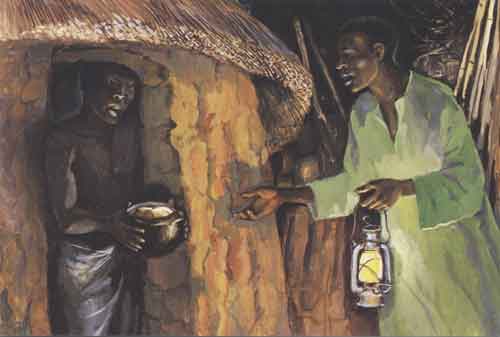

Image: JESUS MAFA. The Insistent Friend, from Art in the Christian Tradition, a project of the Vanderbilt Divinity Library, Nashville, TN. http://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/act-imagelink.pl?RC=48293

Bosco,

Good, helpful reading. And faithful to the Greek and to the culture. Jesus does often leave unclear who is honored and who is shamed, who is host and who is guest– or at least the stories we have from him seem to. That’s part of the fun of his stories. He leaves us to figure it out and see what all might be seen.

I don’t have ALL of the MSS notes for this passage, but I do have the Vulgate (Nestle’s 1906 Critical Edition). And the Vulgate may well have preserved some MSS tradition where we get the perseverance idea. Verse 8 in the 1906 edition of the Vulgate begins:

“Et si ille perservaverit pulsans”

“And if he shall have persisted knocking…”

The critical edition I have notes this is omitted in some previous versions as well. It is also present in the Douay-Rheims (1582), so it had to have in the version of the Vulgate in use at the time (late 16th century).

And of course, it’s not in the standard Greek text we’re probably both reading from.

The deal is, somewhere along the line in the Western tradition, it was there. Maybe it was a gloss to identify what the “anadeain” was in this instance, or whose it was. Perhaps it is a way of seeking to link this teaching on prayer with Luke’s later telling of the “persistent widow” and the “unjust judge.” I don’t know. But the word “persevere” does literally show up– though (I would say) clearly in a gloss.

For the record, my guess is you’re right about this. Luke 11 isn’t talking about perseverance at all.

Peace in Christ,

Taylor Burton-Edwards

Thanks, Taylor. I am not able, currently, to research this further, but yes, my understanding is that there is no interpretation of this text as “perseverance” prior to the fifth century.

The theme of perseverance is found in verse 8: ‘ask…seek …knock’.

Your comment is too short, Kevin, to understand your point. The present imperative in verse 9 (not 8) can be understood in a repeated or continual manner. But that would not be the sole interpretation. That text, obviously, is shared by Matthew (7:7) whereas the parable this post is about is unique to Luke.

I think the word “boldness” in the NIV is reasonably helpful (like impudence or shamelessness)… being bold to ask God seems to fit the context. But I can see some value in the concept of “perseverance” in the sense of following through and asking, seeking and knocking (even if that borders on the unthinkable) instead of saying to the guest “Sorry, I cannot do anything for you; I simply do not have enough, so how could I be expected to welcome you properly?”. Perseverance does not need to mean “continue doing the say thing in a nagging way”.

Thanks for your thoughts, Mark. NIV has, “I tell you, though he will not get up and give him the bread because he is his friend, yet because of the man’s boldness he will get up and give him as much as he needs.” From my post you will see that the NIV words “the man’s” is not part of the original text and has been inserted by the NIV “translators”. As I pointed out αὐτοῦ (of him) could apply to the one within the house or to the one asking. Rather than allow us to think that through, NIV has provided the (non-Greek-reading) reader with only one option and not even a footnote indicating that this is not an accurate translation. Certainly Bailey and Jeremias interpret the parable in this manner. But Fitzmyer, Ringe, and Donahue do not. “Boldness” also does not fit in with the cultural context of the parable, the Mediterranean/ Middle-Eastern context in which shame is such a strong driver.

I did mean verse 9 – lapsus digitae.

Regarding translations, the NIV is a cross between ‘dynamic’ (expounding in contemporary idiom a likely meaning where there is ambiguity) and ‘essentially literal’ approaches (aiming, where possible for one-to-one verbal correspondence, e.g. the ESV). The ESV renders the words ‘anaideian autou’ as ‘his impudence’, while the NRSV opts for ‘his persistence’. The ‘impudence’ or ‘cheek’ of the visitor would be in going at such an awkward time of night (‘my children are in bed’ etc).

I agree with you that persistence is not in view here and the NRSV is wrong. If the meaning you suggest is correct (and I incline to that view), the difficulty is then that ‘anadeian’ (‘shamelessness’ – not ‘shame’) really has to be a very compressed (and otherwise unexampled) way of saying ‘his fear of being shamed if he refused the request for help’.

All of which reminds us that translation is not the same as exegesis (otherwise, what’s the point of preachers?). I imagine it was all a lot clearer in Aramaic!

V. 9a (kai humin lego) establishes a thematic link with this passage, with a call to venture expectantly in prayer. The present imperative could be taken in the sense of perseverance (‘keep on asking’) or repetition (‘ask again and again’).

I would think that shamelessness would be in reference to the petitioner. He has approached his neighbor, and surely a friend, for assistance to fulfill an act of hospitality in spite of the lateness of the hour and the awkwardness or inconvenience for his neighbor. He has done so shamelessly, as one who is innocent. And for the petitioner’s shamelessness alone will his friend get up from his bed and risk rousing the entire household to assist his neighbor in fulfilling this important cultural obligation.

I have several reasons for why anadeian has to be referring to the neighbor inside the house, but perhaps the strongest 2 arguments are the context of the passage and the point of the application.

1. verses 1-4 highlight God’s honor and ability to provide for our every physical and spiritual need. verses 11-13 highlight God’s honor and Fatherly love which can be counted on to provide good gifts beyond what we have asked. it would seem strange to me, then, to tell a story in which the one being petitioned had to be nagged because he wasn’t honorable to meet the request.

2. the application is found in verses 9-10: because of our relationship to such a gracious and honorable God, we are liberated to continually ask, seek, and knock–knowing that God will not answer our prayers with harmful gifts but with good gifts (the Holy Spirit). why should we expect our prayers to be answered? is it because we are strong enough to manipulate God by our persistence or is it because he is honorable and loving enough to give us good things when we ask? i think the latter.