In a comment on Anglicanism losing the psalms, Rev’d Malcolm French wrote, “A huge part of the problem, I think, is a very modernist tendency to believe that we should shape the liturgy rather than allowing the liturgy to shape us.” This post is attempting to open a discussion about shaping worship and allowing worship to shape us.

In October 1943, Sir Winston Churchill said, “We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us.” He was seeking the rebuilding of the House of Commons which had been bombed in May 1941.

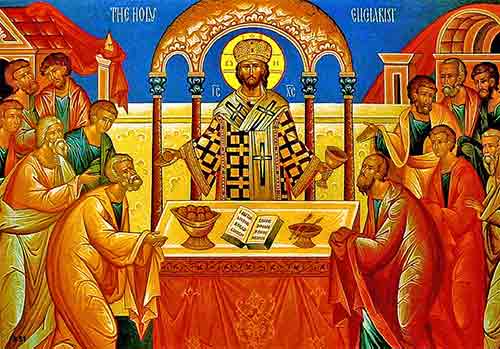

Christians say, “Lex orandi, lex credendi” – our worship shapes our belief. And, of course, our belief shapes the way we live. Are we still allowing worship to shape our belief and life, or have we shifted into a mode in which the dynamic goes essentially in the opposite direction: our beliefs (and lifestyles) shape our worship?

In my thesis, I wrote:

This historical survey of eucharistic worship underscores the aphorism of Prosper of Aquitaine, Lex orandi – Lex credendi, prayer shapes believing. A significant part of this thesis, however, concerns the twenty five years of Prayer Book revision in which Prosper’s claim is turned around, and what New Zealand Anglicans believe became the source of the new way in which they would pray.

The Anglican Eucharist in New Zealand 1914-1989 page 2

Certainly, twentieth-century liturgical reform led to the abandonment of “cookie-cutter” liturgy, copy-and-paste worship. Three decades ago, I wrote:

Services in The Book of Common Prayer have often been likened to “meals on wheels.” They were centrally prepared, and then warmed and dished up locally. One began at the beginning of the service, reading most of it until one reached the end of it. Services in A New Zealand Prayer Book are more like “frozen peas,” or maybe a basket of groceries and a recipe book. A core of essential material is provided with some further resources, other content is added locally. Many will be surprised that the obligatory material from any of the eucharistic liturgies (pages 404-510) takes only about six minutes to recite. Most of the rest of the service is locally chosen. The quality of the meal is now much more dependent on the local “cook”!

Celebrating Eucharist Chapter 1

But, at least in the Anglican Church in Aotearoa, New Zealand and Polynesia, (and you, from another Church, might identify similarly) the reform has not stopped. There has not been a period of time (as in some other Churches) of living deeply into that reform, of allowing it to shape us. Once we started on the our-beliefs-shape-our-worship trajectory, that has become a primary, now-seemingly-unstoppable paradigm.

Even after the publication of the 1989 A New Zealand Prayer Book He Karakia Mihinare o Aotearoa, there continued to be experimental services produced and added to a list (called, excitingly, SLR3). But in 2014 it was acknowledged that this process had no legitimacy and was abandoned. Instead, to allow for continual production of experimentation (remembering that clergy and other licence holders vow and sign they will use only “authorised services”), the Constitution of our Church was altered to allow for wider authorisation, including by bishops.

The Form for Ordering the Eucharist (a bullet-point rite with a framework Eucharistic Prayer) was altered so that it was no longer restricted to special occasions. An Alternative Form for Ordering the Eucharist was passed, a bullet-point rite which extends options, allowing for use of any authorised Eucharistic Prayer from any Anglican Church worldwide. A Template for Worship was passed, essentially: come in – do something – leave.

And then there’s technology. We’ve moved rapidly from books, overhead projectors, and printed sheets, to pretty much every church with even the smallest congregation being able to have powerpoint. For those not creating their own resources, scouring the internet provides a plethora of material.

An unintended consequence is that a lot of clergy’s (and other’s) time and energy is now expended preparing for Sunday’s main service during the week. It is a contemporary echoing of a wonderful insight in the Book of Common Prayer:

Moreover, the number and hardness of the Rules called the Pie, and the manifold changings of the Service, was the cause, that to turn the Book only was so hard and intricate a matter, that many times there was more business to find out what should be read, than to read it when it was found out.

Concerning the Service of the Church

In other words: more time and energy was spent in finding the right thing to say than to say it once found. In our contemporary context – there is a wonderful doctoral thesis: find out how much time, energy, and cost (per congregant as an added kicker) is taken up in preparing Sunday’s main service.

In changing our Constitution to allow bishops to authorise, there is lack of clarity (and disagreement) whether this is limited to authorising rites for which there is no agreed formulary (in other words, a bishop might be able to authorise an induction service, but cannot authorise a new Eucharistic Prayer or Baptism rite); or can a bishop actually authorise any rite even if there is already an agreed formulary – with the exception of the ordinal (which gets specific mention in Title D Canon II 4.3); or can a bishop authorise anything at all? All three positions appear to be held and acted on.

Common prayer, in this context, has ceased to be a shared experience across communities and is reduced to a term that simply describes any group of people praying together. It is now possible that, at the same time on a particular Sunday morning, there is not a single overlap between a service in Anglican Parish A and its neighbouring Parish B. Even within a parish, there may be no overlap whatsoever in what is said and sung at service C and what is said and sung at service D. As such, “common prayer” has ceased to be a term that is particularly apt for Anglicanism and now can equally apply to every worship service from the most free pentecostal service to the most rigidly book following.

In this lack of clarity about what is required, what is allowed, and what is forbidden, I coined the term “Anglican Church of Or“. More recently, following the example of our secular political life, the term “Christian Coalition of Chaos” has sprung to mind. Certainly, everyone is doing what is right in their own eyes (Judges 21:25).

Another possibly unintended consequence is the loss of the rights of the laity, of those in the congregation. Possibly one of the most neglected rubrics (agreed instructions) is that services require “careful preparation by the presiding priest AND PARTICIPANTS [my emphasis].” I am sure we’ve all been at power-point services where we wonder what the next slide will be requiring us to proclaim as something we believe! This is a new clericalism.

If we repeat texts, they sink deeply within us. Shared repeated texts bind us as community and provide a common life framework. Post-modernism is the abandonment of a shared, overarching framework. In abandoning common prayer (as in shared across the Church, not simply referring to community worship in one service at one time in one place), are we in danger of losing what makes us not necessarily unique, but particular, as Anglicans? As I quote on page 1 of my thesis, “Lex orandi is always and everywhere Lex credendi, but very markedly so with Anglicans”

I do not think we can go back to the “meals on wheels” approach of worship. We need worship appropriate to this community in this context. On the other hand, I think we have reached the far end of the pendulum swing – a commodification of God and worship in which people are encouraged to find a worship style that “fits them”, and so within parishes (and other worshipping communities) people worship in shifts with quite different styles, even having two different styles going at the same time on the same site. And if you can’t find what fits you in this parish, have you tried…? And then there are different denominations, if you don’t fit in with this one… rather than having us be moulded by the repeated wear of common prayer, shaped more and more into Christ…

Might we not have a simplified agreed book of common prayer? With, say, half a dozen agreed Eucharistic Prayers, with the same responses, with one of these Eucharistic Prayers having spaces for adding locally-appropriate content? Might we not have simply one greeting and response for The Peace? Rather than the plethora of ones we have now, where we cannot even greet each other, but need to address the book, sheet, or power-point screen because otherwise we won’t know what to say. Might we have essentially one Daily Office, so that even if we are alone, at home, we are inserting ourselves into the Prayer of the Church, rather than simply having a personal devotional time. And a daily reading system that goes: if you are only reading once a day, use this; if more than that, here’s some more options. So that all who pray and read the Bible daily liturgically are at least reading and praying these texts in common – even when alone.

Yes, we may need a new Cranmer – leadership that helps to put the common-prayer toothpaste back into the tube:

And whereas heretofore there hath been great diversity in saying and singing in Churches within this Realm; some following Salisbury Use, some Hereford Use, and some the Use of Bangor, some of York, some of Lincoln; now from henceforth all the whole Realm shall have but one Use.

Concerning the Service of the Church

What do you think? Is worship shaping us, our beliefs, and our lives a worthwhile project? Or is it simply nice history?

Do follow:

The Liturgy Facebook Page

The Liturgy Twitter Profile

The Liturgy Instagram

and/or sign up to a not-too-often email

This is a deep subject, and I feel drawn to understanding it better. My personal appreciation for “high” liturgy is simply not shared by many in my community, so when I do find a service that fits my personal spiritual ethos, it is often empty (there were 11 people at compline last week). The services that are filled with families and kids and people of different backgrounds tend to be quite “low” and non-liturgical (by my definition). I never feel connected to the Holy Spirit on those occasions, although I do feel the interpersonal connection with my community.

My sense is that traditional liturgy is going the way of opera — that is to say that it will be a form of worship that lives on, but in a rarefied way which few are attracted to and experience.

I try and be non-dualist about this — accepting that what I really love about the former way of doing things isn’t really in conflict with newer ways. That difference isn’t “bad” per se, it’s just … a difference.

Very interesting. I am completing my latest book, Language in the Liturgy: Past, Present and in the Future, commissioned by Lutterworth Press, Cambridge, which is scheduled for publication in early 2025.

Thanks! I’ll look out for it. Blessings.