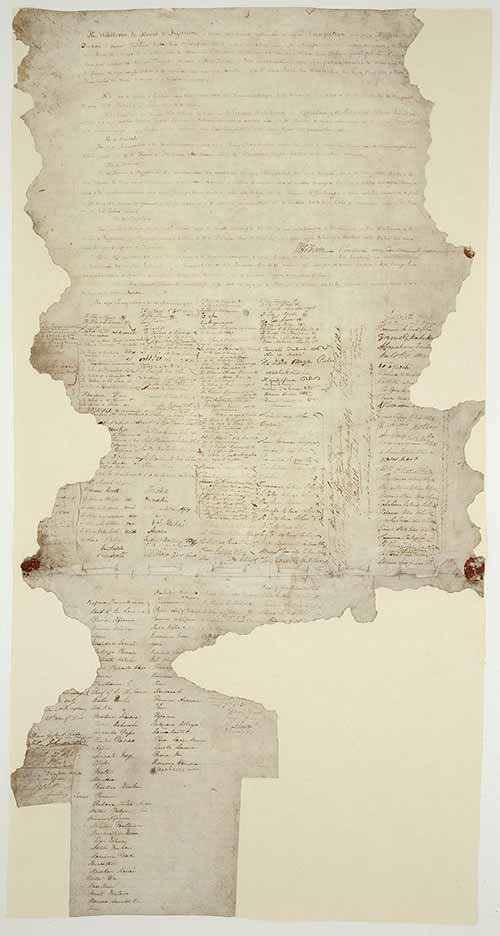

Today, 6 February, we in Aotearoa New Zealand commemorate the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840.

Generally, in this land, religion is underrated. Knowledge about religion (be it Christianity or any other significant world religion) is abysmal. Our educational curriculum, strongly influenced by post-modernism, has little specified content – and that includes no requirement to teach about the Treaty! There is also regular misunderstanding about the distinction between religious education and evangelisation…

Thomas Kendall of the Anglican Church Missionary Society (CMS), one of the first three missionaries to settle in New Zealand, published the first book in Māori in 1815: A korao [kōrero] no New Zealand; or, the New Zealander’s first book; being an attempt to compose some lessons for the instruction of the natives. In 1820 he and the chiefs Hongi Hika and Waikato visited England to work with Cambridge University linguist Samuel Lee to produce the first Grammar and vocabulary of the language of New Zealand.

Thousands of biblical texts were printed and distributed.

In the 1830s there were more and more Pakeha European immigrants arriving in Aotearoa, and there was no real “European/British” legal or justice system here under which these immigrants were clearly bound. Missionaries here were increasingly concerned about the effect of these immigrants on Māori. They believed a formal relationship via a treaty with the British Crown was needed to protect Māori.

In Britain, at this time, there were networks of strong Christian parliamentarians and public servants. The 1830s was when Christians pressured the British parliament to abolish slavery in the British empire. The majority of the people in the British Colonial Office were also part of these strongly influential Christian groups. This office oversaw what was happening in the colonies.

So, in Britain also, these influential British Christians campaigned for the protection of

Māori.

James Stephen, the brother in law of William Wilberforce, was the permanent undersecretary in the Colonial Office. He was profoundly influenced by the life and teachings of Christ, and a big part of the British side of the Treaty’s story.

James Stephen drafted the instructions which were given to William Hobson when he was sent to New Zealand in 1840. These instructions included:

All dealings with the Aborigines for their Lands must be conducted on the same principles of sincerity, justice, and good faith as must govern your transactions with them for the recognition of Her Majesty’s Sovereignty in the Islands. Nor is this all. They must not be permitted to enter into any Contracts in which they might be ignorant and unintentional authors of injuries to themselves. You will not, for example, purchase from them any Territory the retention of which by them would be essential, or highly conducive, to their own comfort, safety or subsistence. The acquisition of Land by the Crown for the future Settlement of British Subjects must be confined to such Districts as the Natives can alienate without distress or serious inconvenience to themselves. To secure the observance of this rule will be one of the first duties of their official protector.

You will recognise the connection with the articles of the Treaty.

Māori saw and see the Treaty in spiritual and Christian terms. The Te Reo name for the Treaty is ‘Te Kawenata o Waitangi’ (‘the Covenant of Waitangi’).

Hobson said to each signing chief “He iwi tahi tatou” (“we are one people”). The missionary, Henry Williams, had come up with those words based on the letter to the Ephesians.

Missionaries with considerable mana with Māori – particularly Henry Williams – took the Treaty throughout the country to be signed. Māori often signed because of the trust they had in the missionaries.

If you appreciated this post, consider liking the liturgy facebook page, using the RSS feed, and/or signing up for a not-very-often email, …

Instagram’s @liturgy is the new venture – if you are on Instagram, please follow @liturgy.

Morning Bosco, In the Local Timaru Hearld today is an article on the new principal in Fairlie of St Joseph Catholic School.

He is well travelled and has decided to come home to teach in the school he went too. He believes that the Christian values need to be taught again so will be connecting the school with the New Priest at the church and the local community. Hopefully he will endeavour to teach more about our local Moari too. Blessings Ruth

Hi Bosco.

I believe Samuel Lee was actually a Linguistics professor at Cambridge rather than a missionary. It was the missionary Thomas Kendall who worked with Hongi Hika and Lee to get Te Reo Māori into written form.

Thanks so much, Neil. I have clarified the text after your helpful comment. Blessings.

Of the various books that have been written showing the history of Aotearoa / New Zealand in the mid 1800’s, the one I think should be compulsory reading by all historians and all NZ Christians is ”The Turanga Journals”, Francis Porter’s selection from and commentary on the journals of East Coast CMS missionary William Williams, the brother of Henry Williams. (Porter, Francis, ”The Turanga Journals”, VUP, Wellington, http://vup.victoria.ac.nz/turanga-journals/, ISBN: 9780705503723). Sadly, it’s out of print, so you will need to find a library copy.

In 1839, we see William getting news of shonky land “purchases” by the New Zealand Company, and lamenting “How can British justice permit this?” Then, in 1840, we see him rejoicing with Henry that the treaty has been signed in Waitangi, the two men confidently expecting that Māori lands and interests are now protected.

As Grey and later governors work to subvert the Treaty, though, we see Williams’ dismay (one shared by all the CMS missionaries), and once again hear the lament “How can British justice permit this?”. And we learn of Williams’ dejection in 1867, after the Land Wars, as (now living in Napier as the Bishop of Waiapu) he reflects about how he may have contributed to the tragedy because of his own pride. (He doesn’t specify how, though.)

The part played by Rev. Octavius Hadfield (later Bishop of Wellington) is mentioned, too. Hadfield was from an aristocratic family and would not recommend to Māori that they sign the Treaty—because, I suspect, his aristocratic background meant he had a less rosy view of “British justice” than the middle-class Williams brothers. However, he used his high connections to press the British Parliament about the injustices that were occurring, though ultimately unsuccessfully.

In short, these missionaries (and not just those I’ve mentioned, but many more) were doing their utmost to protect the rights of Māori, and their influence and actions should not be downplayed or written out of the history books. European-descended Christians can be rightly proud of them, and, learning of their concerns, hopefully join in with the moves to make right what went so badly wrong.

Thanks, Trevor. That is a most helpful expansion of my post. Blessings.