This, as the title indicates, is the third in a series about faith deconstruction. I suggest it is very beneficial if you read Part 1 and Part 2 first.

Wikipedia helpfully summarises:

Faith deconstruction, also known as deconstructing faith, evangelical deconstruction, the deconstruction movement, or simply deconstruction, is a Christian phenomenon where people unpack, rethink and examine their belief systems. This may lead to dropping one’s faith all together or may result in a stronger faith. There is no end goal for deconstruction. David Hayward coined the term for the process he was experiencing when leaving the church. The word is adapted from the writing of Jacques Derrida. It is closely related to the exvangelical movement.

I want to emphasise that deconstruction is a positive part of our faith journey; it is nothing to fear.

The term “deconstruction”, as indicated in the Wikipedia quote, seems to be primarily around American-style evangelical faith traditions. When I asked about this online, one response was that within the catholic tradition, the word “lapsed” is more commonly used. Certainly I contend that, within the catholic/orthodox/anglican/episcopalian faith traditions, liturgy and connection to the contemplative dimensions of Christianity allow for growth through stages, dark nights, doubt; and these traditions encourage an artistic, sacramental, metaphorical, and apophatic appreciation of faith.

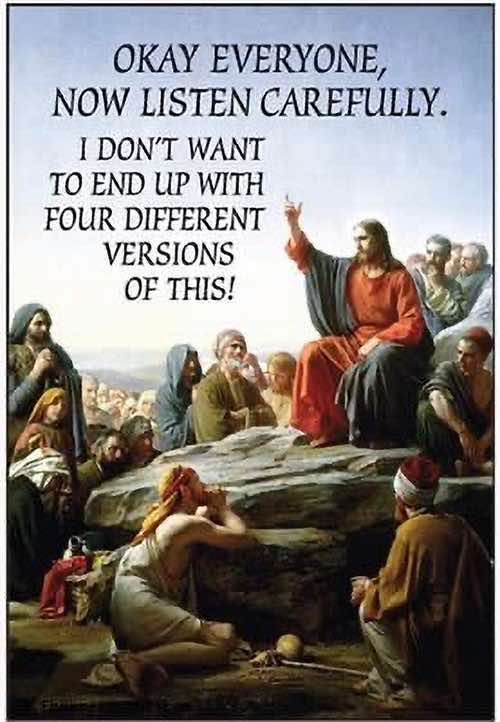

As I already intimated in my previous post in this Deconstruction series, diversity is seen in every facet of the Judeo-Christian scriptures. If God had intended the good news to be reducible to four spiritual laws, why not have such a linear listing of them in his inspired word, the Bible?

In the Bible, there’s no instructions on how to celebrate the eucharist, who presides, who is (allowed) to be baptised (and exactly how), how church is to be structured, and any number of other things that we, followers of Jesus, argue about and split over. Instead, there are four different versions of Jesus’ life – and to those who say they harmonise well, which version of the Lord’s Prayer do you pray? The one in the Didache (not in the Bible)? Good luck getting Christians to agree what Jesus’ parables mean. Then, Luke disagrees with himself, let alone with Paul whose friend he is supposed to be. Abraham is used by Paul to justify “by faith”, and by James to teach the essential place of “works”. The list goes on, and on…

Open the Bible honestly and one finds that the maths-equation, security-camera-truth approach is not what is being offered. Instead, one is offered a different kind of truth.

A movie I watched recently concluded (unusual capitalisation as per the film):

While the Motion Picture Is Inspired by Actual Events and Persons, Certain Characters, Incidents, Locations, Dialogue, and Names Are Fictionalized for the Purpose of Dramatization. As to Any Such Fictionalization, Any Similarity to the Name or to the Actual Character or History of Any Person, Living or Dead, or Actual Incident Is Entirely for Dramatic Purposes and Not Intended to Reflect on Any Actual Character or History.

There was one point in the movie that an event was presented in a way that was physically impossible. When I looked at the interview of the person to whom the event portrayed had actually happened, she said that although what the film presented was clearly impossible, it expressed well what the experience was like for her, and it did so better than a literal, scientific, historical rendition. And I, in the moment I watched this certainly-inaccurate moment in the film, had a small share in what the subject’s reality was.

Maybe there should be a sticker, similar to the film’s disclaimer I quote, inside every Bible. The Bible isn’t a history book – in the security-camera approach. The Bible is a sacred text, and as we immerse ourselves in its world, we are drawn, in our own time and in our own particular context, into the same divine reality that it emerged from. All of the Bible is true – and some of it happened. And it happens again in our lives, yours and mine, today, as we open its pages and allow it to draw us into its upside-down life.

For further reading

Seven years ago I wrote a helpful reflection on the appropriate place of the Bible in our Christian life and church life: the Bible is necessary but not sufficient. I think it complements well this series on deconstruction.

Do follow:

The Liturgy Facebook Page

The Liturgy Twitter Profile

The Liturgy Instagram

and/or sign up to a not-too-often email

I’m not sure ‘lapsed’ is a catholic synonym for all the ways people seem to ‘deconstruct. Another FB friend, currently exploring the subject suggests four categories. To ‘lapse’ was to abandon faith, which would fit only categories 1 or, maybe, 2 below:

“While I’m definitely in the Christian deconstruction crowd, my observation has been that there are four basic strands that comprise this rope:

1. Secular deconstruction away from all religion, spirituality, and/or perception the divine.

2. Sacred deconstruction away from organized religion with reconstruction towards a kind of personalized spirituality.

3. Sacred deconstruction of the certainty in the beliefs and practices of one Christian tradition in favor of certainty towards the beliefs and practices of another tradition.

4. Sacred deconstruction away from Church BS with reconstruction towards The Way of Jesus in a more authentic, genuine, and countercultural expression.

I’m squarely in that fourth group, but have definitely seen a lot of the others and diligently seek to respect, understand, and empathize with the others.

Thanks, Phil – my reply to this fell off when this site went down. Blessings.