As many will know, there is a debate whether to encourage all at a service to receive communion or whether to hold to tradition that only those baptised are welcome at the table. [Let’s leave to one side, for the moment, limiting communion to those confirmed and/or those in one’s own denomination].

Some churches break their denomination’s rules and invite all to communion, stressing the Eucharist being a continuation of Jesus’ radically-open table fellowship. I know of at least one church that represents this architecturally – whilst most have font before table, in this building you move through table to font. Communion there is for all, and baptism is for the committed. In most, there is the practice of baptism for all, communion for the committed.

I was absolutely delighted that our church moved to communion for all the baptised whatever their age or denomination (it had previously been only for confirmed Anglicans, then there was a period of “after ‘Admission to Communion'”). In my ministry I stress communion being open to all the baptised whatever their age or denomination – and I encourage all (babies up) to receive communion from their baptism. In practice I see a shift in understanding of the importance of baptism with this approach – it is full church membership. Communion is the repeatable part of the Sacrament of Initiation.

I would not refuse anyone communion. If I knew someone was not baptised I would speak to them later encouraging them to be baptised, in the understanding that their desire for communion indicated a call to baptism.

There is a regular time when I wince with shame and embarrassment at our church’s (IMO unnecessary) highly-public exclusion of the unbaptised present and publicly highlighting them. When young people come to support their peers at confirmation (or baptism) our NZ Anglican rite explicitly addresses a question only to “baptised Christians”: “Let us, the baptised, affirm that we renounce evil…” (not even the one being baptised can, at that point, join in the renunciation!). Again, at the Apostles’ Creed, only the baptised are to say it.

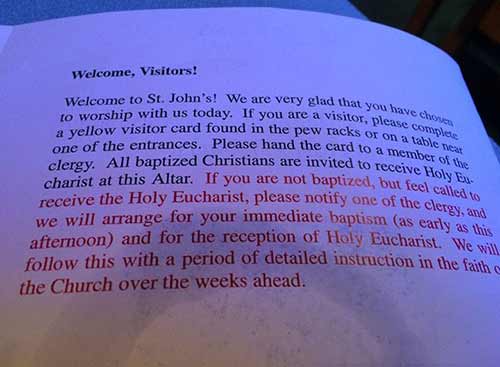

Now I have seen an invitation in a service sheet that people read at a Eucharist (image above):

If you are not baptized but feel called to receive the Holy Eucharist, please notify one of the clergy and we will arrange for your immediate baptism (as early as this afternoon) and for the reception of Holy Eucharist. We will follow this with a period of detailed instruction in the faith of the Church over the weeks ahead.

What do you think of this? I have also heard of churches who set a specific date publishing that they will baptise anyone who turns up at the service wanting to be baptised that particular day. I have even heard of someone seeking baptism in the middle of a service, and the priest doing that. My closest experience has been, as a parish priest, knowing a middle-aged person always present in church but never receiving communion, I visited this person at home and discovered this person was embarrassed to admit not being baptised. With great delight to us both, I baptised this person the next Sunday.

There are other less-heard voices in this conversation. Benjamin Dueholm, Ben Stewart, and Frank Senn in different ways underscore that our ever-expanding eucharistic hospitality may have swung too far and become aggressive. Members of other world faiths, atheists, or others who do not want to receive communion may be present at a Eucharist but not want to have the spotlight on them for not receiving communion.

a kind of aggression in our hospitality that is left when we don’t grant anyone a means of opting out. A problem with the desperately unqualified invitation is that it makes staying in one’s seat look an awful lot like being ill-natured. Why else, after all, would anyone not wish to break bread with us? “Is there a pastorally appropriate way to invite a devout Muslim to communion?” Ben Stewart asks, and I admit I don’t know what that would look like. Not every unbaptized person is a “none.” And inside every “none” is not a Christian waiting to be invited out. One aspect of hospitality is allowing people to refrain, not just for the sake of their own scruples but for the sake of an expectation of conduct that they might not wish to bear at their nephew’s first communion service. It is possible to drop our communal barriers so fully as to define everyone, including our Hindu or atheist neighbors, as suddenly part of a mystical body that we happen to be specially privileged to identify. [Read the whole thought-provoking post here]

What do you think?

I know that I’ve complained about Christians who try to say there are no differences, and militantly say that all are one. Yes, I’m looking specifically at those behind Holy Women, Holy Men in the Episcopal Church. By inclusion of non-Christians in the calendar, we are baptizing the dead, just as the Mormons have famously done.

The point of how we make those who feel that are not receiving is important. After all, Paul points out that there are times that Christians shouldn’t be receiving, let alone someone who isn’t making any preparation at all because they are not a Christian.

An interesting connection, Bob. Blessings.

An interesting read. It seems like getting someone to sign a piece of paper declaring they are a Christian as though that act alone means that they go from exclusion to inclusion. I recall doing the signing thing and telling someone after a Gideon’s address at high school but had both wondered about God well before that and was not consciously Christian until many years later. The baptism that matters is the one God does with the Holy Spirit and sometimes its hard to determine exactly when that was.

This certainly raises some interesting questions. I have had feedback from one person that our church seemed very unwelcoming, because we said *only* baptised people could take communion and that put her off returning.

We actually say all the baptised are welcome – and are silent about the rest. But silence is not the same as invitation.

On the question of “aggressive hospitality” we need to be better at respecting anyone’s choice to take or not take communion. This is a strength in the Catholic Church – that it is quite alright not to go up and only your closest friends or family are likely to say anything, if at all.

As for people of other faiths – I would like to leave it up to their conscience. I have participated in Buddhist prayers without anyone asking me what my faith is. In doing so in a informed way, understanding what is going on and knowing what it means for me. I would like to extend the same courtesy in return.

And I had assumed you had mocked up the pew sheet as a joke. I think it is a bit alarming to me that church would really do that. Feels a little too much like a shot-gun wedding to me.

And as an aside – why do they get *visitors* to fill in a card. A visitor is someone who is passing through the parish – so what reason would they have to collect information on them.

I assume they intend to target people who are first time attendees, who may well come back regularly. But is a major mistake to get them to fill in forms on their first Sunday.

And it all goes through the clergy – which means there is no lay ministry of welcoming.

So wouldn’t encourage me to return if I saw that.

All very interesting points, thanks, David. And as you saw by the link – the image is not mine. Blessings.

This is a matter of great importance. In my own very traditional Church of England parish we moved a few years ago from communion that was shared only by the confirmed, to the admission of baptised children over the age of seven who had completed a course of preparation. Immediately that raised the question of unconfirmed adults, and I admitted them too, usually trying (sometimes successfully) to enrol them on a confirmation course. My personal view, now quite aidely shared, is that baptism is sufficient regardless of age, and that for us this is a necessary next step. It requires the bishop’s permission. But (to surprise myself) I don’t altogether have a problem with offering a completely open table, a practice usually associated in the CofE at any rate, with those of a much more evangelical bent than me. Bishops Michael Perham and Mary Gray-Reeves in their excellent study ‘The Hospitality of God’ (SPCK, 2011)spend a lot of time examining and celebrating different emerging churches and fresh expressions in the USA and UK and noting the trend towards open communion. Then right at the end, the brakes get applied, First Corinthians is quoted and they even resort to canon law (Perham, I suspect). But this also is said:

‘The move from a model [of church] that sees belonging as emerging from believing to one that accepts the reverse is a major shift that calls for radical rethinking of how we ‘do’ church, including how we initiate people into membership and how we celebrate the sacraments. It is only the fast-changing cultural context that can seriously challenge the way we have interpreted the biblical material and a tradition that goes back to the sub-apostolic age. Even in that context, there is a need for the church to be wary about ‘spiritual tourism’ – people simply experimenting with what seems good for them without a sense of serious searching or commitment. Eucharistic participation cannot be reduced to just being there ‘to snack’. For all the danger that it may sound like compromise, we need to celebrate a God whose sense of order does not extend to narrow prescription or to conditional grace. It may be the will of God for the Church that the Eucharist should be the ultimate expression of communion with the Trinity and with one another within the Body of Christ, but that does not prevent it being a means of grace for those who, on their way to faith, find themselves for a moment incorporated into something that they are not yet ready to commit to or meeting with one who they are not yet ready to embrace. The outcome of that may be a church that puts more emphasis on invitation than on qualification, but is also ready, by good teaching and gentle leading, to move people who have stumbled into eucharistic participation without knowing its full significance, to the baptismal water and to a sense of being part of the Body. In other words, if they find themselves regularly at the table, they should learn very soon about the font.’

I can sense the authors working through the shift in their own minds as they write – the views are held in tension. The question I want to raise is: Is it necessary to know about the ‘full significance’ of eucharistic participation in order to receive it as a full ‘means of grace’? And how many of the baptised and confirmed (and even ordained) faithful apprehend the ‘full significance’ in a way that exhausts its infinite mystery? Increasingly I think that although they are indissolubly linked, it may be good policy, particularly with those sampling belonging as a prelude to believing, to treat eucharist and baptism as separate saramental entities, not making one dependent on the prior reception or even the future intention of engaging with the other.

Thanks, Paul, for your thoughtful points.

Thankfully, the NZ Anglican Church has had baptism for all the baptised as our formal, canonical policy for quarter of a century. I think “full understanding” of the Eucharist is clearly a nonsense limitation. Full understanding of food does not seem to be required for food’s effectiveness! There is value in understanding how food works as one grows.

I think the line of “commitment” is much thicker than suggested.

I would not go with your final sentence, however. I cannot see how we can hold “indissolubly linked” with “treat as separate”.

Blessings.

what I think is that this smacks of desperation, anything to make up the numbers.