Whether you regard the Christmas Season as concluding on Christmas Day, Epiphany, the Baptism of the Lord, Candlemas, the Sunday following Candlemas, or are Orthodox, or Armenian, and celebrate the Incarnation on another day and see the season differently… this is a reposting of an important reflection.

We tend to speak about “secular” as if it is the human foundational operating system, and that, somehow, religion is superimposed as an application, a program, on top of that (choose from some popular programs, all doing similar things); as if atheists declutter the unnecessary program, getting back to the foundational operating system – secularism.

But a moment’s examination of the secular operating system helps us spot that this is particularly a post-Christian phenomenon. It is no accident that secularism is born from Christianity – it has the incarnation, unacknowledged yes, at its heart. Secularism isn’t an abandonment of the sacred. The secular is finding that the ordinary is sacred.

Peter Wehner, a senior fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center, helpfully highlighted this in an article, The Christmas Revolution.

- The incarnation affirms the delight we take in earthly beauty and our obligation to care for God’s creation. This was a dramatic overturning of ancient thought.

In Plato’s dualism, there was a dramatic disjuncture between ideal forms and actual bodies, between the physical and the spiritual worlds. According to Plato, what we perceive with our senses is illusory, a distorted shadow of reality. Hence philosophy’s most famous imagery — Plato’s shadow on the cave — where those in the cave mistook the shadows for real people and named them.

This Platonic view had considerable influence in the early church, but that influence faded because it was in tension with Christianity’s deepest teachings.

- “Christianity was to introduce the notion that humanity was fundamentally identical, that men were equal in dignity — an unprecedented idea at the time, and one to which our world owes its entire democratic inheritance.” in A Brief History of Thought: A Philosophical Guide to Living (Learning to Live)

by Luc Ferry.

- We moderns assume that compassion for the poor and marginalized is natural and universal. But actually we think in this humanistic manner in large measure because of Christianity.

- It helps those of us of the Christian faith to avoid turning God into an abstract set of principles. Accounts of how Jesus interacted in this messy, complicated, broken world, through actions that stunned the people of his time, allow us to learn compassion in ways that being handed a moral rule book never could.

What do you think?

If you appreciated this post, consider liking the liturgy facebook page, using the RSS feed, and/or signing up for a not-very-often email, …

Instagram’s @liturgy is the new venture – if you are on Instagram, please follow @liturgy.

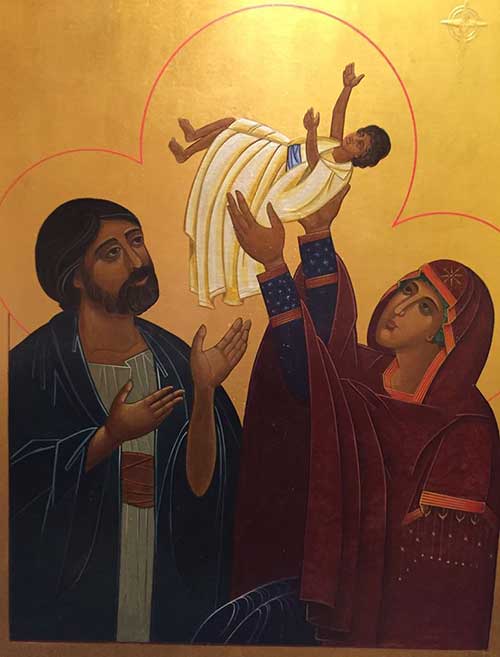

Please can you give the source for that icon? It’s joyous!

Thanks, Helen. I am sorry, I do not know the history of, name of, nor who wrote that icon. If either of us (or someone else) discovers it, please let all know here. Blessings.

The faux Byzantine image above the OP would be even more joyous if it were in a modern style that did not appropriate conventions that are sacred tradition to Orthodox. If something in these conventions seems sacred somehow that is just because so many of them have been reserved to a particular tradition of devotion since well before 781. Using them as filler, exoticism, or kitsch mocks that devotion.

Somehow, the visuality of the most reserved of all Christian traditions has gradually become the default image stock of the internet. Need a picture of Jesus, get a Byzantine icon. Cliche, click, done. Interesting. What keeps people who think in a modern Western way about God and images, history and the sacred from using the work of so many accomplished artists nearer their own mindset?

Put another way, if one thinks like oh Salvador Dali, Georges Roualt, or Marc Chagall, or here maybe Eric Gill or Stanley Spencer, why would one not use their work instead, so that the chosen image actually reinforces one’s carefully worded point? True, most cliche-clickers are not deeply enough acquainted with either the sacred arts or patristic theology to hear the dissonances– desensitising oneself and others to the sacred is what makes profanation wrong– but if the OP is itself an historical one then it should be itself the clue to culturally consonant work. Given the argument here, why not an image from the time of Wilberforce fighting slavery in the British Empire?

My two guesses– I welcome better ones– are: (1) the sudden illustration of everything has pressed the unready to face the question, what about an image can be sacred?; (2) many have layers of resistance to identifying any recent style with God– and more layers of resistance to analysing the resistance itself. Suddenly we want sacred images, but not any of the ones we know. While we run from our own spiritual and cultural traditions, it is just easier to break in and steal from another one and hope that the owners and curators are not overly offended.

Indeed, this image is offensive. It has mainly five theological problems. (1) Jesus does not have the “Ὁ ὬΝ” in the halo. (2) Jesus lacks two-coloured cloths, speaking of his godhead and humanhood. (3)

Mary does not have the inscription “MP ΘΟΥ”, not the three stars on her robe, but only one. (4) Joseph is a young man. (5) The three halos are joined together, when, in fact, Jesus’ halo should impede on the two others. In conclusion: this is a heretical image, denying the incarnation itself.

Hmm. It’s hard for me, coming from the U.S. where the concept of freedom of (and from) religion is enshrined at the top of our rights, to think of “secular” outside of the political realm. When I think of your operating system analogy, I think of secularism being more in line with Net Neutrality — an “agreement” that each person may find their own “foundational operating system” without being forced by the State. So my thinking is that religion is not an add on–but the origin and the framework and we have agreed not to “throttle” it.

I do agree that (again here is the U.S.), when “secular” is used, it is frequently used as if it were in conflict with religion. That’s as wonky to me as saying science and religion can’t co-exist. You’ve boshed this before, especially given your training. And I also agree that many “secular humanists” would feel that they have claim to equality, fighting poverty, as so on. As my mother said, “humpf” (the southern US translation would be “bless your heart.”) :o)

Great read. Something I needed on this day when the temps are starting to dip to below zero. Fahrenheit. Blessings!

Thanks, Stephen. From outside of USA, of course, USA’s use of “secular” is skewed by the mention of God on your money, the chanting of “God bless America” by politicians of every stripe, and the regular call to your nation to pray by your presidents etc. Thanks for the encouragement. Blessings.

Oh, I agree. We’ve wandered far from our Constitutional ideals. Permanently adding “In God We Trust” to our money, along with adding “under God” to our Pledge (replacing “E Pluibus Unum”, which I feel is much more in line with our founding fathers’ thoughts) was an outcome of the 50’s. Cold War reactions against the “godless communists”.

The calls to prayer from our politicians ring very hollow here to a large percentage of the people, especially since we tend to find that the most vocal political adherents to public prayer tend to be the ones caught with their pants down, so to speak.

I thank you for all your hard work on this site. Really one of the most thoughtful and thought-provoking sites. Not an easy addition to your “day job”, I’m guessing, but quite appreciated.