One of the most controversial points of the new English Mass translation is the Nicene Creed. Not just the “consubstantial” but more especially the “For us men and for our salvation he came down from heaven.” The translation acts as if it is a formal equivalent translation – where the same word in Latin is translated by the same word in English. And the translation insists that “propter nos homines et propter nostram salutem” be translated as “for us men…” So far so uninclusive, but it really hits home when we look at the Gloria: “…and on earth peace to people of good will…” translating “et in terra pax hominibus bonae voluntatis”.

Hominibus is the plural masculine and feminine dative of homo, meaning a human being, man, person. Homines is… ummm… ummm… plural masculine and feminine accusative of, well what a surprise(!), the exact same word, homo. According to the papal rules it should be translated by the same English word, but the papally approved translation fails: people in one place, men in another.

Interestingly the NZ priest’s book, presumably a typo(?), has for the new text of the Nicene Creed, “for us and for our salvation”. [NZ Roman Catholics have begun using the “people’s parts” of the new translation].

The Vatican has made over 10,000 alterations to the English texts that left the Bishops’ Conferences for the Vatican’s approval. ICEL is less than impressed. My discovery, merely quickly flicking through the text, is reinforced by a list of 13 types of errors the Vatican is guilty of:

1. change of meaning from the Latin original (RT 41)

2. mistranslation of the Latin (RT 20)

3. limiting of the vocabulary (LA 49/51; RT 20, 46-50)

4. additions of an element not found in the Latin (LA 20)

5. omission of an element found in the Latin (RT 44)

6. weakening of Scriptural allusion (RT 6, 36)

7. loss of intensity of original (RT 50/62)

8. introduction of a theological problem (RT 102)

9. difficulty with English grammar or usage (LA 44/74)

10. adoption of Neo-Vulgate when an antiphon uses the Vulgate (LA 37/38; RT 37/107)

11. capitalization of LORD when it renders YHWH. (LA 41c; RT 81/116)

12. suppression of a rhetorical device (LA 57a/58/59)

13. translations of ‘unigenitum’ (RT 81)

It may be a little while before NZ Roman Catholics spot the issues. Following my predictions, the not-used-at-Mass-previously Apostles Creed is being preferred to the Nicene Creed, the latter being far more significantly altered, uninclusive in language, and with the now-famous “consubstantial”. The Gloria is not used during Advent.

I have already pointed out that the Lord’s Prayer does not follow the Vatican’s requirement. And it interests me that, while the Received Text does not include the contemporary ecumenically agreed English-language Lord’s Prayer, the NZ edition does.

The lack of responses to the NZ experience of using the new texts is due to a variety of reasons, not least loyalty. But in several conversations there is irritation that clergy are putting spin on the new texts by extreme denigration of the texts which have helped them grow in faith for four decades. One newspaper article compared the new texts as an oak dining table to replace the formica and chrome suite used for the last 40 years. One does not enhance the authority of and respect for the papacy by running down the texts authorised through several recent papacies.

Further information: Pray Tell

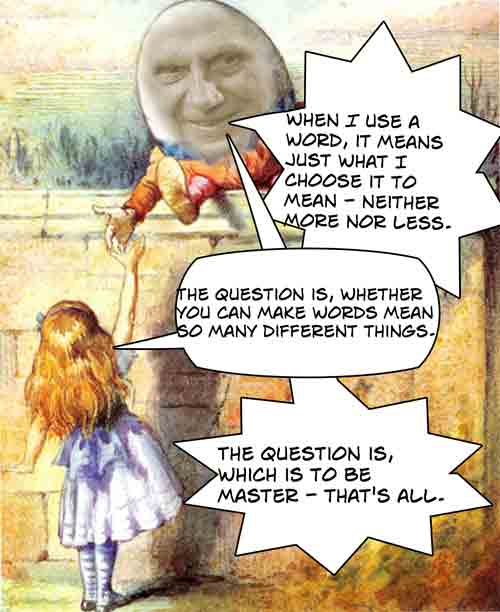

Image source: directly quoting a conversation in Chapter 6 of Through the Looking Glass.

perhaps we could refer to the changes as ” 10,000 altercations…” just for fun???

When I saw the changes that had been made and how they were described as being closer to the original Latin in their meaning I was not impressed at all. In my view we should return to the Latin Mass. It really isn’t that difficult to learn and understand the Latin Mass; – if after all my high school years of having Latin taught to me as if it were a punishment for being naughty I can still manage to decypher the meaning in my middle years then anybody can do it.

The problem is the liturgy is neither in good English, Latin, Greek, Hebrew or Aramatic (as either vernacular or root languages) but with no disrespect to those from the Netherlands, it is in Double-Dutch. Perhaps we should adopt Esperanto! La Lordo esti kun vi. Kaj kun via spirito.

Here is a very interesting comparison of the Collect for Gaudete Sunday. We should be rejoicing, perhaps even vested in Rose rather than Purple or Blue. Hoever the link below will make anyone with a liturgical sense weep and grind their teeth.

http://www.praytellblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/12/3rd-Sunday-Advent.pdf

How good the 1973 version is: clear and to the point, with humanity. what a shame to change it – the follow-ons are wordier and just don’t hit the target.

I am sorry, “AncientSoul”, but anonymously attacking people as doing the work of the devil does not conform with the comments policy, however lenient I have been recently. The rest of what you write can just as appropriately be applied to your comment itself.

maybe a better translation would read: “for us humanity” ?

I understand, Arturo, one of the issues some perceive (I never have myself!) with “for us and for our salvation” is that the worshipping community may perceive this as referring solely to the “us” gathered. Whereas it (clearly) means “for all”. This criticism of “for us and for our salvation” is fascinating coming from those who support the alteration in the Eucharistic Prayer from Christ’s blood being shed “for all” to “for many” (when clearly the original used an idiom meaning “for all”). I think, following the Vatican rules, the translation of the Gloria and the Nicene Creed should be consistent. I think contemporary English can no longer use “men” to validly translate males and females.

Bosco,

people and men mean basically the same thing in the Creed. Always using the same noun would be somewhat strange, as when we say men, we say “us men”. “Us people” just don’t look right.

However, I do know that the reinclusion of “men” has annoyed the gender inclusive types who prefer all terminlogy to be neutral. As you aren’t Catholic, I of course do not mean you, as this doesn’t affect you. I used to always add the men back into the Creed, as I did grow up saying it, and missing it out just because it could mean men, but not women, just seemed silly to me.

Good to see that you are starting to learn Latin!

Thanks for your contribution, Lucia Maria. I think you are missing the point. You need to read Liturgiam authenticam and the Ratio translationis – a lot of people are finding the new translation “somewhat strange”, but the principle is of “always using the same” English word for the same Latin word. The criticism is of this translation which purports to follow formal equivalence, but in fact doesn’t. Also it purports to be an approval of the text presented by English-speaking Bishops’ Conferences but in fact isn’t. The bishops are reminding the Vatican from its own regulations that “the Bishops must commit themselves to this work [of translation] as “a direct, solemn and personal responsibility” (LA, 70)” The English-translation Roman Missal has on its title page, “For the use of…those Dioceses in which the Bishops have approved it by law” – this again gives the impression that the Bishop of the Diocese has the ultimate authorisation of the text, not the Vatican. The contemporary usage of “men” is not irrelevant, but not primary. You may understand “men” to be “people” but I posit most contemporary English speakers do not. Most contemporary English speakers would make little sense of a sentence such as, “God created two men and placed them in the Garden of Eden.” In the past that may have worked, and it may still work for you, but I suggest that for most people it no longer is contemporary English usage. The translation purports to be (with the obvious exception of the Lord’s Prayer) into contemporary English.

Be careful, Bosco – WikiLeaks has released a cable from the kiwi ambassador to the Holy See warning that the Vatican has found out about your plan to release your encyclical “Romanorum Coetibus” seeking to draw in Catholics disaffected by these liturgical changes, and has dispatched a squad of fanatical Polish “tourists” to Christchurch…

‘hominibus’ isn’t ‘masculine and feminine’: grammatically it’s a masculine noun in Latin, even though its meaning can be inclusive (sometimes it means ‘men and women’, sometimes it means just ‘men’). In Attic Greek, anthropos (which is actually the word used in the Nicene Creed) can be grammatically masculine or feminine, but is grammatically only masculine in NT koine.

The trouble is, that since ‘man’ and ‘men’ have become focalized to mean only ‘males’, there isn’t any elegant equivalent left in English. ‘human being’, ‘humankind’ and ‘humanity’ can sound clumsy and biological or broader in scope than ‘man/men’ (‘humanity’ often means something like ‘kindness’). ‘people [of good will]’ isn’t a perfect translation either as ‘people’ can have an ethnic reference in English.

Kevin, I have been noticing an increase of German tourists here lately… Oh wait!

I think “Romanorum Coetibus” would certainly work elsewhere – unfortunately, in NZ the Anglican Church is in liturgical chaos; not a missed opportunity to steel sheep, but a missed opportunity to serve those who will now probably cease to go anywhere.

In the context of my earlier:

What do you call someone who speaks three languages? Trilingual

What do you call someone who speaks two languages? Bilingual

What do you call someone who speaks one language? …..

…English (or American, or a Kiwi,…)

you may confuse some readers by stating “hominibus” is grammatically a masculine noun in Latin. Grammatical gender, dear non-Latin-speaking reader, is to be distinguished from biological, social, or “natural gender”. Hence, Kevin ‘s point, that the Latin grammatically masculine word can refer to both “men and women”.

Please, let’s not get into the Greek original of the Creed, or people might notice that the start of the new “translation” doesn’t correspond to the Greek original at all. The Vatican’s stated intention is to translate the Latin – this is what I am focusing on. That the Latin alters the original Greek is a whole other story 🙂

Yes, all this gender reassignment is a tricky business. Try explaining to students that ‘fatherland’ in Latin (‘patria’). French (‘la patrie’), Greek (he patris) is feminine, however, ‘das Vaterland’ is neuter, but among ‘les Anglo-Saxons’ as the French misname those nations, it has mysteriously become the ‘motherland’ (Mother Russia, too) – no, better not try…

Thanks, Kevin, you illustrate well the point that though hominibus is a masculine Latin word, that does not mean that all hominibus are masculine 🙂 Those who do not have agility in more than one language regularly struggle to understand the issues involved in translation.

I regard leaving out “men” as at least as serious an error as introducing “filioque”. “Imas tous anthropous” is clearly inclusive and the only English equivalent is “for us men”.

The English language is deficient in not having different words for human beings generally and for male adults, as Latin “homo” and “vir”, Greek “anthropos” and “ander” and Zulu “umuntu” and “indoda”. If people can’t live with the deficiency, mthen I suggest that “men” be retained in its inclusive sense, and for the exclusive sense we revive the old “wermen”, and stop talking about “men and women” and instead talk about “weremen and women”.

The alternative is to find another word for the inclusive sense of “man”. I suggest “thpic”, which is an acronym for “the human person in community”. Then we can say “fur us thpics and ouor salvation”.

BUt until that happens, I will use “men” for the inclusive sense and “males” for the exclusive one.

In the Orthodox Church there are probably at least 30 different English translations, most of them bad. Some of them say “for us and for our salvation”, especially in America where it is more important to be politically correct than theologically correct, though I suspect that it also makes it easier for people to slip into thinking that what it really means is “for us Greeks and our salvation”.

Thanks, Steve, for your contribution. Firstly, Steve, this is explicitly not a translation of the original Nicene Creed as is clear from the very start. The original begins in the plural, Πιστεύομεν, not the singular, Credo. This is a translation of the Latin liturgical adaptation. The rest of your comment confuses me, because the Gloria is quite happily translated with the word “people” as the word for human beings.

I have worshiped in Orthodox Churches in America and to my recollection have never heard any variant which omits “for us men” in the phrase when said in English.

Certainly the OCA doesn’t omit it I have just checked and nor does ROCCOR, I’d be surprised if they did.

But my late father collected bilingual service books and I have been able to locate a Romanian one issued by the Patriarchate in 1977 and given the imprimatur of the Patriarch Justin.

The English and Romanian are on opposite pages.

The relevant phrase in entirety

Likewise a Greek version issued by the Church of Greece in 1966 for use amongst the Diaspora, in particular the children of the same with instructional notes as to the meaning of the Liturgy

I’ve typed this and may have made errors – hopefully not but I can provide scans of the pages if required

Thanks, Andrei. That’s interesting, but as I have said, this post is about the English translation of the Latin, and being consistent as the Vatican requires in a formal equivalence manner. This is not about a translation from any other original than the Latin.

Sorry I stuck an oar in, then. I thought there was some discussion of the best English terms to use.

Please don’t apologise, Steve, and thanks again for contributing. I was merely clarifying that this is not a translation of originals behind the Latin text, but of the Latin text as such; and the claim is that it is a formal equivalence translation.

https://wikispooks.com/w/images/6/63/2010_Order_of_Mass_Final_US_color.pdf

The USA has a final edition nearly 12 months out. The NZ half-pie effort seems yet to have no final and definitive text.

Or until the next revision and next set of so-called “translation rules.”

Thanks, Phillip. There is criticism this week in the NZ Catholic (the fortnightly paper) of the poor (read inaccurate) translation in the now-suddenly-popular, previously-not-used-at-Mass Apostles’ Creed of “he descended into hell“. It would be interesting to compare your text to the one I provide. I notice that both the one you provide and the one I provide do not include the contemporary, ecumenically agreed English language Lord’s Prayer that is part of the NZ RC texts. I wonder if anyone can explain that?

Maybe I’ll be called biased because I’m male, but I don’t see “For us men … [he] became man” as being non-inclusive language. It’s just trying to present the Latin (and Greek) in English.

The Latin of the Creed has “Qui propter nos hómines … homo factus est.” The link between “homines” and “homo” (present in the Greek too: “ἀνθρώπους … ἐνανθρωπήσαντα”) should be noticeable in vernaculars too.

Some have suggested “For us people … he became a person,” but that’s theologically incorrect: the Son has always been a Person.

Others have suggested “For us humans … he became human,” which I think we can all agree sounds a bit peculiar and sci-fi. Some make it “For us human beings … he became a human being.” I still find that lacking, at least in poetry.

Some present an uneven translation altogether: “For us (and for our salvation) … he became man”, “For us (and for our salvation) … he became a man”, “For us (and for our salvation) … he became one of us”.

I think all of these pale in comparison to the poetry and integrity of “For us men … he became man.”

Thanks Jeffrey for joining the conversation. Possibly in some places, maybe in your country, “men” is inclusive: I saw three men standing on the corner of the street; God made two men and placed them in the Garden of Eden; Some of the men were wearing very attractive dresses; James found many of the men attractive. But in English as I speak it, and as it is used in most places I am aware of, men = males. So if we are translating the Latin into English, men just will not do. IMO.

Furthermore, to follow your point in your second paragraph, then, as I have highlighted, the Gloria should be translated, “…and on earth peace to men of good will…”. So are you happy with the Nicene Creed, and arguing that the Vatican needs to alter the Gloria so that “The link between “homines” and “hominibus” (present in the Greek too) should be noticeable in vernaculars too”?

Your examples, while provocative, are exceptions. I don’t know of anyone who uses the word “men” when he means to speak exclusively of women, but the word “men” can be used to speak both of males, or males and females together.

In my country, women can be chairmen. We speak of “no man’s land”, and free-for-alls are “every man for himself”, but the ladies aren’t left out. Some sharks are man-eaters, but females are not safe either. God created man in His own image: male and female He created them.

In the Creed, I think L.A. #30 is the guiding principle: “When the original text, for example, employs a single term in expressing the interplay between the individual and the universality and unity of the human family or community (such as the Hebrew word ’adam, the Greek anthropos, or the Latin homo), this property of the language of the original text should be maintained in the translation.” The Creed clearly juxtaposes homines with homo.

There is no such link in the Gloria. The word “homo” occurs once in the Gloria, as “hominibus.” It is translated as “people” in the current, 2008, and 2010 translations, and I don’t take issue to it. I could tolerate it being “men”, but the necessity for that choice is lacking… although the Catholic RSV does use “men” in Luke 2:14. (The NAB translates it as “those”!) In the end, it comes down to: different location, different context, different rules.

LONG STORY SHORT: I am fine with “men … man” in the Creed. I think it is the most appropriate English translation of the Latin. In the Gloria, I could go with “men” or “people”. I don’t see “men” as being an exclusively male word in every context.

P.S.: Attempting to make the Creed inclusive by saying “for us and for our salvation” you run the risk of speaking exclusively, as if the Body of Christ is speaking only of themselves, and not for all mankind; I think “for us men … [he] became man” avoids that misconception.

Thanks, Jeffrey, for your ongoing contribution. You say my four examples are exceptions. In what sense are they exceptions? They were just written without pausing. You say, “I don’t know of anyone who uses the word “men” when he means to speak exclusively of women” – in not one of my examples am I speaking exclusively of women: “I saw three men standing on the corner of the street; God made two men and placed them in the Garden of Eden; Some of the men were wearing very attractive dresses; James found many of the men attractive.” Furthermore, if “men” for you is inclusive of women, why would there be any issue whatsoever to use “the word “men” when he means to speak exclusively of women”?! Your unlinking of the Gloria from the Creed seems to be a rather random regulation. As to your ps. I have already commented on that. It seems again a very random justification in a translation that now has Christ’s blood shed “for many” (the gathered community exclusively) when the original clearly meant for all. I am also visualising a community of monks saying, “for us men and for our salvation…” Now tell me, that anyone listening to them with English as their first language in our contemporary world immediately thinks that they mean women as well…

Thanks, David. I’m totally with you. There comes a moment when our ears pop and we can no longer hear exclusivist language without it just grating. Everything in NZ is in contemporary English. I can just see trying to get a document written here, or legislation through parliament, with someone arguing “the word “men” can be used to speak both of males, or males and females together” – forget it. It just wouldn’t get past first base. The reality is, the Nicene Creed will be little used by RCs in NZ. For the first time RCs are allowed to use the Apostles’ Creed in the Mass. That’s already the preferred option now – even though RCs are complaining the new word “hell” there is not an accurate translation. But that is another story 🙂

Jeffrey, I think that part of your argument against the lack of poetry and the awkwardness is just the fact that you are unaccustomed to it, so yes, at first it seems queer.

As one who has dealt with inclusive language, at least in English, as it is much different in Spanish, since the early 1980s, I can tell you that when I hear un-inclusive language it immediately grates on my hearing. It is immediately awkward to me, and I feel discomfited at its exclusiveness, especially when used in the liturgy.

I prefer For us and for our salvation…he became human.

I suspect that “inclusive” language is as grating to my ear as “exclusive” language is to you, David.

Bosco, I’m not sure you’re getting my comparison of the Gloria and the Creed. The Creed uses “homines … homo”. The Gloria does not, it just uses “hominibus” once. The translation of “hominibus” needn’t be subjected to the same specific rules that apply to the translation of “homines … homo”, because the circumstances around “homines … homo” are different. I don’t know how better to explain it.

And I don’t have a problem with “pro multis” being translated as “for many”, either. (I do take issue with “I believe in one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church” in the Creed — the word “in” shouldn’t be there!)

Thanks, Jeffrey. I see you are not explaining why you think my four quickly-constructed sentences are exceptions, or why a group of women could not be called “men” but if one man is present (sorry, male is present) then you can use the word “men” for such a group, however large. The difference with “inclusive” language being grating to your ears, is that this is the direction that English has now taken. All legal documents, all acts of parliament, all instruction manuals, all newspaper articles, etc. must increasingly be grating on your ears – because that is how English is now spoken and written. Words change. “Awful” used to mean, “inspiring wonder” – a good contemporary translator would no longer use it in that way. “Prevent” has similarly changed – to the opposite of its earlier meaning. And so on.

I had understood the Mass translation to be a single piece. Your translation of a word in the Gloria completely differently to the same word in the nearby Creed makes little sense to me following the formal equivalence principles. The Nicene Creed will fall out of usage here inspite of complaints about the inaccuracy of “hell” in the Apostles’ Creed. The addition of the word “in” (as well as “man”) appears as subliminal advertising 🙂 Since you mention the Greek, let’s not even go to the change from original plural to singular 🙂

You have not responded here to NZ RCs using the ecumenical Lord’s Prayer. It seems, hence, that not merely spelling will vary from one English text to another.

The “for many” in the Eucharistic Prayer will have catechesis that “for many” here means “for all”. That being the case, it should be translated as “for all”. Above all else, translation is about translating meaning. Not about what individuals do and don’t have a problem with.

Thanks again for presenting your position here. It is useful and valued to have respectful discussions here.

Bosco, your four examples seem to me to be places where using “men” inclusively leads to confusion, whereas the use of “men” in the Creed does not strike me as confusing. I guess it’s subjective.

I acknowledge that some English words have changed in meaning over time. But that doesn’t mean we have to do damage to texts that use these words in their former sense. I think we are smart enough to adapt our minds to the words. I don’t mind saying “Lord God of hosts”… I know I’m speaking of the heavenly hosts of angels, not Eucharistic hosts.

The word “homo” has more than one definition, so I do not see how translating it ONE way in one circumstance, and translating it ANOTHER way in another circumstance, is opposed to the principles of formal equivalence.

The word “man” is not an addition to the Creed; the word “in” IS an addition. The Catechism of Trent explained rather clearly that while we believe IN God the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, we do not believe IN the Church:

“With regard to the Three Persons of the Holy Trinity, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost, we not only believe them, but also believe in them. But here we make use of a different form of expression, professing to believe the holy, not in the holy Catholic Church. By this difference of expression we distinguish God, the author of all things, from His works, and acknowledge that all the exalted benefits bestowed on the Church are due to God’s bounty.” (Creed, Article 9)

The concept of “translating for catechesis” is the sort of thing which got us “not worthy to receive you” instead of the rich and scriptural “not worthy that you should enter under my roof.” When you translate for catechesis, you inevitably lose elsewhere.

I have not responded here about the ecumenical Lord’s Prayer being used by Catholics in New Zealand because I didn’t know I was expected to. You know from our conversation on Twitter than I only found out about it from you, yesterday. I don’t know what comment I have to make on this matter, since I consider myself ignorant of it.

I will defer to the Tridentine Catechism on the matter of “for many” in the consecration of the wine:

“The additional words ‘for you and for many’ […] serve to declare the fruit and advantage of His Passion. For if we look to its value, we must confess that the Redeemer shed His blood for the salvation of all; but if we look to the fruit which mankind have received from it, we shall easily find that it pertains not unto all, but to many of the human race. When therefore (our Lord) said, ‘For you,’ He meant either those who were present, or those chosen from among the Jewish people, such as were, with the exception of Judas, the disciples with whom He was speaking. When He added, ‘And for many,’ He wished to be understood to mean the remainder of the elect from among the Jews or Gentiles.

“With reason, therefore, were the words ‘for all’ not used, as in this place the fruits of the Passion are alone spoken of, and to the elect only did His Passion bring the fruit of salvation. And this is the purport of the Apostle when he says: ‘Christ was offered once to exhaust the sins of many;’ and also of the words of our Lord in John: ‘I pray for them; I pray not for the world, but for them whom thou hast given me, because they are thine.'” (Sacraments, The Holy Eucharist)