Let’s not let facts get in the way of our prejudices…

Ian Paul presses for the protestantisation of Anglicanism at his Psephizo site – this time urging bishops to throw away their mitres.

Without any historical justification, The Rev. Dr Paul contends that the bishop’s mitre derives from the headgear of the High Priest! And this becomes part of his reasoning “why bishops in the Church of England dropped the wearing of mitres from the Reformation onwards.” It is certainly correct that lack of historical knowledge and understanding have resulted in persons with prejudices against certain practices making poor decisions.

Even if Dr Paul’s mitre-origin myth had any historical truth to it – which it doesn’t (he’s only one step away from claiming that the mitre is worn to represent the pagan fish-god Dagon) – recounting something’s genesis does not determine its current usage or meaning. Anyone with an interest in etymology, as just one example, will know that a word can change meaning significantly with time – sometimes to the opposite of its original. Christianity regularly uses metaphors and images ironically and subversively.

Dr Paul’s post then goes on to an allegorical interpretation of mitres. Once we overlay the liturgical landscape with an allegorical map we are bound to get lost in theological la-la land.

Let’s apply some allegory to Dr Paul’s own dress sense. In his post, he describes himself as wearing a suit and tie. I wonder how often he reflects about his tie allegorically as being the most widely used and the most multicultural of all phallic symbols, a contemporary replacement of the more overt codpiece. I note that Dr Paul in his post concludes with the “serious objection to the wearing of mitres” by linking mitre-wearing directly to Bishop Peter Ball’s abuse of children! I wonder if he has done the statistical analysis of abuse by tie wearers in comparison to mitre wearers.

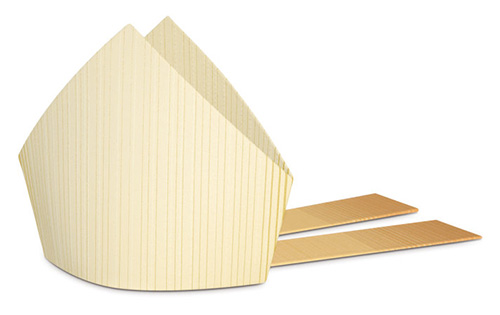

The actual history of mitres developed from headgear used in a variety of contexts, secular and religious. It was a soft cap which by the twelfth century had a sort of dent in the middle (the ‘direction’ the dent was worn varied). What we normally see now is a development in the baroque period. I would advocate for contemporary mitres to be significantly lower and simpler.

The rest of Dr Paul’s post is so riddled with inaccuracies as to be hardly worthy of commentary. The majority of bishops in the world wear black – not his purple. Clearly, Edward King (Bishop of Lincoln 1885-1910) was NOT the first English bishop to have worn a mitre. Ordination does not just “set people apart in terms of training and supporting them to minister.”

The mitre, of course, is one of the most-recognised and most-used Christian emblems – from chess to heraldry.

All discussions such as this need to be set within the context of reflection on vesture (and being part of the great river of the church catholic). Why vest at all? Why not simply wear your tie – its length, size, shape, and where it is pointing being a focus of eucharistic presiding?

*****

That mitres conform to (read “required by”?) the the Church of England’s BCP Ornaments Rubric will be part of a future post.

H/T to Peter Carrell who alerted me to the Psephizo post and clarified that this is an expurgated version of it that we are reading. Dr Paul’s original was Trump-like in its focus on how Bishop Rachel Treweek looks and could never look good in a mitre – with the least flattering photo of her wearing one that Dr Paul could find.

If you appreciated this post, do remember to like the liturgy facebook page, use the RSS feed, and sign up for a not-very-often email, …

Hi Bosco

When did the first bishop of Christchurch regularly wear a mitre?

(I suggest iit was in the Pyatt, or 1960s and 70s era).

Why, if mitres are important to bishoping, did it take so long for Anglican bishops, between Reformation and today-ish, to assume the mitre?

And what drove the assumption?

Symbolism? Allegory? Mimicking Rome?

My own understanding from my Pyatt era youth is this interestingly shaped headgear was symbolic, of the Holy Spirit, which, of course, flowed from the bishop’s hands at confirmation and ordination!

Good questions, Peter. Your research could continue with – has sex abuse increased with the increasing wearing of mitres in NZ? Do our bishops who are women look any different to our bishops who are men wearing them? The idea of the Holy Spirit flowing from the bishop’s hands is new to me. And why wearing something on one’s head would symbolise that image is lost on me. Blessings.

No, Bosco, I am not interested in the further questions you note. I am interested in why bishops wear mitres when once they did not. It was once explained to me that the mitre looks like the flames of the Holy Spirit, illustrating the Spirit-anointed ministry of the bishop as ordainer and confirmer.

You seem to pour scorn on that understanding, but given it was provided when I were an impressionable lad, it was not for me to question the authority of my betters.

As a matter of fact I do think symbolism is important to robing. Why am I wearing this rather than that? Why might all priests wear this rather each priest what they feel like? Why do bishops wear mitres and priests and deacons no head gear? (No, wait, the Canterbury cap???) Does symbolism have no contribution to make to our discussion of these things and our explanations to those who ask “why”?

I would distinguish, Peter, a spectrum between symbolism and signs, and suggest allegorisation is not the doorway into allowing symbolism to speak to us. Sure, when you were a child, spoke like a child, thought like a child, reasoned like a child – you might have found allegorising signs helpful. But when you and I became adults, we put an end to childish ways. One way is to denigrate the signs. Another is to denigrate the allegorisation. You may have chosen the former. I have chosen the latter. Blessings.

My overall point is that if bishop’s want to wear headgear, with or without symbolic or allegorical significance, could we please have a good old Anglican conference about what headgear looks better than mitres, always, noting comments below, keeping an eye on the counter-cultural. Even a cardinal’s skullcap or an orthodox bishop’s hat, in my view, is more satisfactory to the eye than a mitre!

Thanks, Peter. I will second your motion to our synod that this, rather than the usual obsession, become the focus of heated debate, hermeneutical hui, respectful listening, Lambeth and Primates’ Conferences, etc. Blessings.

My liturgy & worship professor, Dr Marjorie Proctor-Smith, PhD, who received her doctorate as the first Protestant woman to graduate from the program at the University of Notre Dame in Illinois, taught us that the bishop’s miter is from the headgear of a Roman judge. However, the difference being that the judge’s miter covered the ears so that they could not be swayed in their judgment and the bishop’s ears are uncovered so they may hear and offer mercy.

You don’t need a mitre to tell if it is a bishop… just look to see if they move diagonally! (More seriously, after thinking about how church buildings impact of church membership, and how important the Salvation Army uniform has been, plus the significance of Samson and John the Baptiser visually standing apart, there is probably something very important in choice of clothing).

As I have remarked elsewhere:

1. I suspect wearing a mitre conforms more closely to the ornaments rubric than not wearing a mitre.

2. Any baby boomer (or older) claiming to tell us what young people want needs to shut up and check their privilege (says this technical boomer).

3. It seems odd to blame Anglo-Catholic headwear for the sins of an evangelical archbishop.

4. I think there’s at least an argument to be made that it is important that mitres all look a little ridiculous in order to teach bishops humility. (Insert touching story of late Canadian bishop who faithfully wore the hideous precious mitre a faithful parishioner had made for him. He always sighed and cringed a bit before putting it on, but he honoured her gift. Of course, it was worse for everyone else because they had to look at it.)

Great points, thanks, Malcolm! Blessings.

Better a miter than the uniform of the market place as in a business suit that all religious charlatans, sales folke, “televangelists”, preachers, is there any difference wear!

An important point, thanks, Andrew – the life of Jesus has counter-cultural dimensions. Blessings.

Theological la la land, may I have your permission to use that at some point in the future ( I’m still smiling)

If it gets publication, Alistair, I hope I get a footnote. Blessings.

An amusing and interesting discussion. Much appreciated – thanks for sparking it, Bosco.

I had, however, always thought that a necktie was just an ornamental way to conceal shirt buttons. Phallic significance did not occur to me. (I’m not saying you’re wrong – just that it’s an entirely new thought!)

You’ve got me really worried now, Trevor! What is it about buttons that they need concealing?! And why do women not need to conceal them?!!! Blessings.

Most clergy shirts in the US are designed so that the buttons are hidden. That way you don’t have the white tab followed by a desending row of buttons down the front.

https://www.churchsupplies.com/store/media/womens-clergy-shirt-purple-sw-112.jpg

http://alpharobesales.com/images/mensshirts/ClergyShirtSM116.jpg

Yes, that is the same here, David. Hence, if the issue is Trevor’s “concealing shirt buttons” – you don’t need to create a tie to do that as your clergy shirts demonstrate. Blessings.

So this takes us back to the vestments controversy that shook the Elizabethan church, which was bound up with the rise of Puritanism, which ultimately led to Richard Hooker’s great defense of the Church of England and its right to determine “things indifferent.” I remember reading Hooker in college and realizing that there was a wider (and saner!) world than the one I experienced in my evangelical childhood. I think I’ll stick with Hooker.

Yes, I think Hooker is pretty great, too!

The first Anglican religious services in what is now the United States took place in 1565 at the French Protestant colony of La Caroline in Florida, the year that this famous Vestiarian (Edification) Controversy crested within the Church of England. And the first celebration of the Holy Mass (Holy Communion, Lord’s Supper) by an Anglican priest in what is now the US took place in 1579 north of San Francisco Bay, the same year that Richard Hooker, received Holy Orders.

There is an old myth from the Victorian era that has survived even into the twenty-first century, which says the surplice was only “rarely used” by clergy in American Episcopal churches during the sixteenth, seventeenth, eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Over the years this Evangelical folktale has been discredited by a number of historians who have established that there are actually frequent references to surplices as gifts, purchases, or items of upkeep in the vestry reports and other parish records that were compiled during the Colonial and Early National periods. Indeed, a surplice was an item in what is likely the very first set of ecclesiastical appurtenances sent in 1619 to St. Mary’s Church in Virginia for which there is a written record. (St. Mary’s was likely a High Church parish, and is likely the first Anglican church in the new world to be named for a saint—the BVM. )

The fact that many Virginia parishes during the 1720s had no rectors or curates and relied on laymen to read prayers may have contributed to the legend that early Anglican clergy did not often wear the surplice here. Lay readers who served as parish Clerks usually wore a black Anglican cassock and bands. In some High Church parishes the Clerks did wear one , and this also was the case in the Court Churches and Chapels of the Royal Governors such as Trinity Church Wall Street, NYC and the King’s Chapel in Boston.)

Kurt Hill

Brooklyn, NY

Mr Hill, I”m fascinated by what you’ve shared about the first Anglican eucharist in what became the US having been celebrated in – of all places – the Pacific coastal region! It’s such a departure from the pattern of how many of us – well, anyway, I myself – have assumed Anglican Christianity spread on this continent. Could you trace how an Anglican priest came to find his way to that area so early? Was it via a migration across Canada? Very interesting!

FWIW Dom Gregory Dix surmised that the miter went back to the “mitra” or headband worn by deaconesses in the exercise of their office, assisting with baptism of women — to keep their long hair in place. One wonders if this has some connection with the “authority” (exousia) women are to have on their heads (1 Cor 11). Perhaps only women bishops should wear miters?

My lateral thinking is engaged by this, Tobias. Even in the days when only men could become bishops, they changed their surname in the same manner as women did… Blessings.

Some still do take the diocesan name, at least on formal documents… as in +Justin Cantuar, etc.

Mitered abbesses (and abbots) are a thing too… I still have a lovely old sculpture of Abbess Etheldreda of Ely, purchased in the cathedral shop… and wearing a miter!

Yes, Tobias. Thanks. That practice happens also in NZ still, even as women also continue to change their surname on marriage. Furthermore, mitred abbots are known here too. And I hope people are aware of the tradition of mitred abbesses that you refer to. Blessings.

Just one viewpoint from an ancient (81) Sydney C.of E.parson. On the one hand, the wearing of copes and mitres by bishops has become more common in my lifetime – and increasingly more elaborate (at the same time as the importance of bishops in our society has greatly declined). I think this often gives an impression of pomposity and encourages self-importance among the clergy at the expensive of the rest of the people of God. Adopting Roman customs such as purple and red buttons on cassocks makes things even worse, and coats of arms on scarves are not much better. At the other extreme, few of the clergy wear any special robes at all. Our bishops most commonly wear suit and tie in church- which also looks absurd when here in Australia suits and ties are not often worn.

In the spirit of what was suggested long ago in C.S.Lewis’ Screwtape Letters, I would be happy if we moved back from both extremes, with all clergy normally wearing cassock and a graceful surplice (not the Italian cotta and certainly not adorned with effeminate lace), academic hood – if possessing a Biblical or theological qualification, and scarf (or stole if desired for the Sacraments) and if bishops most commonly wore rochet, chimere and scarf, with a simple cope (and mitre if they wish) on special occasions. The latter was the practice of the bishop by whom I was ordained, Bishop Ernest Burgmann of Canberra and Goulburn, one of the truly great bishops of the Church of Australia in the 20th century. (On rare occasions he did wear vestments – plain, unadorned and white.)

Thanks so much, John, for your helpful comment.

It is particularly fascinating, and worth further reflection, that in your context bishops vest in traditional, conservative, formal attire (ie. suit and tie) in the abandonment of the church’s tradition and, as it were, starting afresh.

If you have read my book, Celebrating Eucharist, you will know that, like you, I advocate for vesture that is simple yet beautiful. You and I suggest different ways of doing this. I do not find the rochet with its fussy cuffs does this. The surplice you describe is essentially an alb. I see little reason to wear a cassock, which is essentially a traditional long coat, under the alb. The simple alb is a strongly ecumenical garment.

I would not see the purpose of, say, wearing a Maths degree hood (my first degree) – the stole indicates the church’s authorising of our teaching ministry – not the university (similarly for the chimere). In all, I advocate against the placing of signs upon signs (as you do) – some vesture ends up being akin to a walking advertising billboard.

Blessings.

Not to put too fine a point on it, but the case may be made that the reason for wearing cassock under the alb is the same reason – or one of them – that women wear slips under skirts and dresses: aesthetic. (the other, of course, is modesty.) Like skirts, albs simply look better if they’re not just “hanging” from the waist, but are supported by the cassock. Of course, it’s arguably cruel and unusual punishment in New South Wales in January or Arizona in July.

Thanks, Daniel. I have no idea how one would “hang” an alb “from the waist”. Nearly every alb I see is worn without a cassock under it – and they look absolutely fine. So, sorry, I really have no idea what you are talking about. Blessings.

The cinture?

Cheap cotton might just hang and could use a petticoat!

But most modern cassock albs, such as made by CM Almy in the US, are from fine fabrics that hang well. And some are especially suitable for warmer climes.

I think that Parson John has a point or two here to consider. However, I hope he appreciates the fact that the High Churchmen/women (Anglo Catholics) also have differing viewpoints about ceremonial and doctrine.

As I see it, there are at least three basic trends or tendencies within the High Church tradition: 1) the trend that has always favored “traditional English Usage.” Fr. Percy Dearmer and Canon Vernon Staley are probably good representatives. Full, Gothic chasubles, copes, Canterbury caps, incense, holy water in baptismal fonts and stoups, private recitation of the rosary etc. Very much in the tradition of Laud and the Caroline Divines. This trend represents much of the Sixteenth, Seventeenth and Eighteenth century High Church customs prevalent in the UK and in America during those centuries. “Old” High Church parishes such as Trinity Church Wall Street, NYC and St. and James King Street, Sydney are probably good contemporary examples. 2) The “Continentalists” of the mid-to-late nineteenth century. Introduction of the most current trends within Continental European liturgical reforms, including the influence of Roman Catholic, Old Catholic and High Church Lutheran traditions. Often very Italianate. Fiddleback chasubles, white gloves, plenty of lace on vestments, birettas, flinging holy water (asperges), public recitations of the Rosary, etc. St. Mary the Virgin, NYC and Christ Church St Laurence, Sydney come to mind. 3) Anglo Papalist trend. Liturgically much like the Continentalists, but with a “corporate reunion” with Rome perspective. At one time fairly widespread in the UK, but never very popular in America. Graymoor in Garrison, NY and Mount Calvary Church, Baltimore, were long examples until they swam the Tiber years ago…

Kurt Hill

Brooklyn, NY

Thanks, Kurt. Liturgical reform and renewal has, obviously, also impacted the traditions. And, clearly, it has crossed from High-Church/Anglo-Catholic so that, as I wrote years ago, ‘Wearing them can no longer be construed as promoting a certain “churchmanship” or theology of the Eucharist.’ Blessings.

Can I add – it is in SYDNEY DIOCESE that few of the clergy wear any special robes at all.

The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (3rd ed. rev.) informs me that the crown-shaped mitre of Eastern Orthodoxy was originally worn only by the emperor, and was not taken up by bishops until after the fall of Constantinople in 1453. In the West, mitres are attested not earlier than the eleventh century. This article alleges that the Western mitre comes ultimately from the papal “camelaucum” (mentioned as early as the eighth century in the Liber Pontificalis), the ancestor of the papal tiara, which is described as “an unofficial hat worn chiefly in procession.” I wonder if the popes at first granted other bishops the right to use such headgear as a mark of honour and affiliation, not unlike the pallium.

Church of England bishops may have given up wearing their mitres for a time, though they continued to use them in their heraldry. And of course they still wore them at coronations until at least that of George III — so informs me the Hierurgia Anglicana. I find references only to copes in the accounts of the coronations of William IV and Victoria.

What I hadn’t realized is that from at least the seventeenth century the Archbishops of Canterbury were still buried with painted or gilded metal “funerary” mitres that rested on their coffins, an example of which was recently unearthed:

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/men/thinking-man/remains-five-missing-archbishops-canterbury-found-accident/

So at least they were willing to be “caught dead” in popish vestments. 🙂

The first American bishop, Samuel Seabury (d. 1796), when performing episcopal functions, wore a mitre of black satin embroidered with gold, displaying on the obverse side a cross, and on the reverse a crown of thorns. But he wore it with his scarlet academic hood (and therefore, I presume, with either a surplice or a rochet and chimere).

Thanks, Jesse, for these added points, which enhance the post and complement Kurt’s and other comments. Blessings.

Obviously Dr. Paul has not read any of the inventories of vestments—copes and miters included—seized from cathedrals and parish churches by the Puritans during their brief theocratic dictatorship in the UK in the 1640s and 1650s. It is misleading to claim, as some Evangelical (as well as some Anglo Catholic) writers do, that prior to Pusey, Newman, Neale, et alia most Anglican parish churches and chapels were just bleak displays of Puritan-like severity. In America, it certainly was not the case. No far away Oxford dons, or groups of English Ritualist enthusiasts were required to rescue us Episcopalians from the patterns of “puritan austerity” we daily saw around us in other American denominations. Indeed, the first American Anglican bishops (the irregularly consecrated non-jurors John Talbot and Robert Welton) were both said to have worn copes and miters “in their offices” in the 1720s here. Our first “regularly consecrated” bishop (1784), Samuel Seabury, owned two miters and always wore a miter when he functioned episcopally. Dr. Thomas Claggett, the first Episcopal Bishop of Maryland, wore a miter from his consecration in 1792 until his death in 1816. It is so frustrating when folks such as Dr. Paul repeat again and again old myths and misinformation about pre-Tractarian Anglican customs. I could scream: “Read Dr. Graham Parry, for heaven’s sake!”

These mirror image, mutually reinforcing, myths have been promoted both by Evangelicals, and some Anglo Catholics, for over a century and it’s WAY PAST TIME they be put to rest. The new scholarship has clearly demonstrated that if seventeenth, eighteenth and early nineteenth century Anglican/Episcopal churches, chapels, clergy etc. were not as multihued and highly ornamented as they would be during the Gothic Revival era, neither were they generally of the austere plainness commonly associated with the Puritans, the Quakers, and the other non-liturgical Protestants.

As Dr. Clare Haynes has noted, for example: “Religious pictures or sculptures were erected during the 100 years before the [1660] Restoration, and the necessity for repeated programmes of destruction suggests immediately that there were differing standards of what constituted a Reformed church. Religion in England was thus not all of the plainness of Puritanism, the fervor and political dominance of which tends to overshadow our understanding of this period.”

In America, for example, one of the central Evangelical myths says the surplice was only “rarely used” by clergy in American Episcopal churches during the seventeenth, eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Over the years this legend has been debunked by a number of historians who have established that there are actually frequent references to surplices as gifts, purchases, or items of upkeep in the vestry reports and other parish records that were compiled during the Colonial and Early National periods. Indeed, a surplice was an item in what is likely the very first set of ecclesiastical appurtenances sent in 1619 to an Anglican church in North America for which there is a written account.

Kurt Hill

Brooklyn, NY

Thanks very much, Kurt, for these actual details. A photo relating to your points is here. I have tried to encourage Dr Paul to engage with the actual history, in the comments section here. Blessings.

I know you have tried, Fr. Bosco, and I–and others–appreciate your efforts. You have more Christian patience with folks such as Dr. Paul than I do…Even when confronted with empirical evidence that contradicts their version of things they simply refuse to admit that they could be wrong. Those of us who take history seriously have often had to revise our hypotheses when the facts require. So when we serious history students say something adamantly, you can be sure we have the empirical evidence to back up that statement…I learned that when I wrote and defended my BA thesis of 1972…

Kurt Hill

Brooklyn, NY

Now explain Purple Shirts.

I don’t know who you are asking, Michael. As I said, ‘the majority of bishops in the world wear black’ rather than in Dr Paul’s post where they wear purple. Blessings.