I am regularly asked: why do we read the Passion account on Palm Sunday? The expectation from those inquiring is often that Palm Sunday should focus on the joyfulness of the Triumphal Entry by Jesus into Jerusalem (a sort of second Laetare/Refreshment Sunday in Lent). And that reading the Passion story should happen on Good Friday.

Let’s highlight at the start of this post: the majority of Christians gathering on 24 March (2024) will hear both the story of the Triumphal Entry AND the proclamation of The Passion (both from Mark).

We can find services in the early church where people read the story of Jesus’ Triumphal Entry (Egeria in Jerusalem, passing from there, as so often happened, to Spain and Gaul) on the Sunday before Easter Day. Also we have accounts of reading the Passion (in Rome, and churches that Rome influenced on that Sunday.

Let’s also keep in mind the early church practice of a catechumen period (up to three years – Apostolic Tradition 2:17) of formation prior to baptism at the Easter Vigil. Lent was the final, intense run-up to Easter baptism companioned by the already-baptised faithful. The catechumenate decreased and the penitential, rather than baptismal, focus of Lent grew. The last two weeks of Lent became a period focusing on Christ’s suffering (“Passiontide”) complete with the veiling of cross and statues. This began on “Passion Sunday”; Palm Sunday was the “Second Sunday in Passiontide”! This latter began with a Solemn Procession of Palms (with Matthew’s Gospel version); the Mass itself proclaimed Matthew’s Passion.

In Anglicanism, there was no palm rite or mention from 1549 to 1662 Books of Common Prayer, and the title was simply the “Sunday next before Easter”. Nor was there a mention of “Passion Sunday” in those years.

Vatican II called for a renewal of the Church Year, revival of the catechumenate (Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults – RCIA), and refreshing the lectionary (Sacrosanctum Concilium, the Constitution on the sacred liturgy 1963, approved 2,147 to 4). The revised Roman Catholic, three-year cycle of readings includes proclaiming FAR more of the First Testament and nearly three times as much of the New Testament. [The Revised Common Lectionary is an ecumenical revision of this system with even more attention to the First Testament as well as to stories about women.]

We now have the Sunday before Easter Day, beginning Holy Week, being Passion Sunday with the Liturgy of Palms.

Before we continue, for those interested, here are catechumenal rites on this site (acknowledgement):

Lenten preparation (catechumenate)

receiving the Lord’s Prayer (catechumenate)

receiving the creed (catechumenate)

enrolment for baptism (catechumenate)

The history is clear: BOTH the Palms Procession (with its reading) AND the Passion are associated with the Sunday prior to Easter Day. When you try and find out why both are read in today’s church on this day, you find a lot of explanations that people can’t (or don’t) get to the Good Friday service (including noting that for RCs it’s not a “Holy Day of Obligation), and so reading the Passion on Sunday is a pastoral decision to avert the tendency to leap from the joy of the Triumphal Entry to the joy of the Resurrection (and skipping over Jesus’ suffering). That pastoral concern may have been in the back of people’s minds, but not in the forefront of liturgical renewal.

In fact the Passion read on the last Sunday in Lent can be seen more akin to the overture at the beginning of Holy Week. Christ enters Jerusalem triumphantly as king, but his kingship is elucidated in the Passion; the Cross is his throne.

I have written on this topic previously. This post attempts to expand on that, but let me include, here, some points that I haven’t yet made here.

Formal rites for Palm Sunday typically begin with a Liturgy of the Palms including reading a Gospel account of Jesus’ entrance into Jerusalem. Such rites then proceed, a bit later, to reading the Passion from one of the Synoptic Gospels (this year, Year B, that is from Mark). The Passion in the Gospel of John is read on Good Friday.

Older forms in Church History tended to have a procession with palms with the Palms Gospel read and a Eucharist with Matthew’s Passion. The other Passion accounts were read through Holy Week. The Sarum rite and different editions of the Book of Common Prayer reflect this way of doing things.

The “Sunday next before Easter” was originally Passion Sunday. Shifting Passion Sunday to the previous Sunday was part of the development of calling this, simply, Palm Sunday – lengthening periods of commemoration is part of liturgical history. The earlier approaches have been restored in seeing the Sixth Sunday in Lent as being Passion Sunday with the Liturgy of Palms. This is the approach followed here in my (free online) book Celebrating Eucharist.

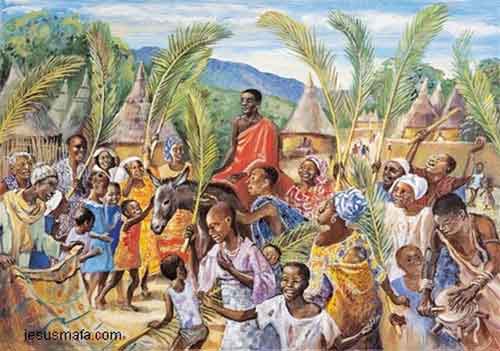

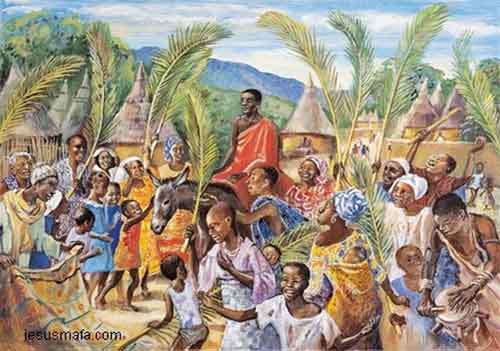

People will do all sorts of other things, of course, not mentioned in agreed and formal rites: donkeys are a common addition, for example.

Omitting the Passion Reading on the Sixth Sunday in Lent, and reading only the entry into Jerusalem with palms, is part of a tendency to turn liturgy into historicised re-enactment. This post is not a deprecation of using our imagination to be present in the biblical accounts, but liturgy, and the liturgical year, is much, much more than pretending. It is worth reflecting on why riding an actual donkey is not even presented as an option in formal and agreed Palm Sunday rites.

Those who reduce liturgy to imaginary re-enactment often go on to celebrate a Passover Seder on Maundy Thursday. If your community does this, please rethink this practice by reading this.

Liturgy is much more and much deeper than pretended re-enactment. If the re-enactment approach is followed, your community should omit the Last Supper story from the Eucharistic Prayer on Palm Sunday, because that hasn’t happened yet. And, in the Eucharistic Prayer, commemorating Christ’s death and resurrection should be omitted. Next we need to move the celebration of the Annunciation to before Advent, and certainly not have the Annunciation after Christmas and the baptism of Christ – and where it falls this year, horror of horrors, at the start of Holy Week.

No, liturgy is, on Good Friday for example, commemorating Christ’s death in the presence of the Risen Christ. Christmas is celebrating the Incarnation – not simply imagining a cute baby and being moved by our human instincts around babies – and the incarnation is celebrated with bread and wine to make present the Incarnate One’s death and resurrection.

Yes, we celebrate Christ’s death and resurrection in liturgy – but we do so not simply to re-enact past events – the purpose of liturgy is that we might be incorporated more and more into these events; the purpose of liturgy is not to have Christ die over and over again in our imagination; the purpose of liturgy is that we die and rise again a bit more each time – individually and together.

Do follow:

The Liturgy Facebook Page

The Liturgy Twitter Profile

The Liturgy Instagram

and/or sign up to a not-too-often email