I have been researching web best practice in order to keep this site cutting edge, and user-friendly.

There are some obvious conventions:

- a clickable header/logo in the top left that sends you to the home page.

- a navigation bar across the top or down the side

- links in the footer to some secondary level importance information

- links in a text indicated clearly, mostly with underlining, normally blue

- …

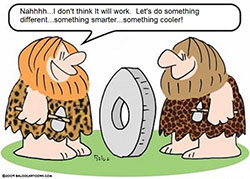

Quite simply, because they work. Conventions only become conventions if users find them useful.

The same is true for liturgy. And don’t tell me, “our worship is ‘non-liturgical’.” My understanding of “liturgy” = “community worship”. Even in so-called ‘non-liturgical’ worship you can see conventions.

For up to 2,000 years and, in some cases, back into Christianity’s Jewish roots, and often from normal human interaction in groups, the conventions we follow in liturgy are there… because they work… because “users find them useful”.

There are conventions in drama and film. There are conventions in language and grammar. There are conventions in human interactions. There are conventions in liturgy.

Someone who seeks to create drama or film without knowledge or skill of conventions is heading for failure. Someone who seeks to be a published writer without knowledge or skill in language conventions, grammar, or spelling is heading for failure. Someone who seeks to lead worship, or who has been specifically designated/commissioned/ordained to lead worship without knowledge or skills in liturgical conventions is…

Someone who seeks to create drama or film without knowledge or skill of conventions is heading for failure. Someone who seeks to be a published writer without knowledge or skill in language conventions, grammar, or spelling is heading for failure. Someone who seeks to lead worship, or who has been specifically designated/commissioned/ordained to lead worship without knowledge or skills in liturgical conventions is…

and the one who so designated such a person is irreverently irresponsible.

Those clergy and other worship leaders who vow and sign up to the agreed conventions without making any effort to know them let alone conform to them IMO are doubly reckless.

Yes, conventions can be broken. To startling effect. But only after profound knowledge, understanding, and experience of the convention that one is breaking.

A convention may not work well. If, after having tried following the convention rigorously, having researched its origin, and the best-practice understanding of this convention, you find a better way of achieving what the convention aims to effect, then there is justification for altering the convention. If you have vowed and signed up to following the convention there may be a process that one goes through in order to alter the convention that you have committed yourself to. But, as my original source highlights:

Warning: Break Only If You Know What You’re Doing

*****

And, yes, regulars here will see (may notice) some alterations to this site as time permits. But alterations will be following best-practice, carefully-researched, user-attuned website conventions.

*****

Those interested in exploring some foundational worship conventions could start with my (free online) book Celebrating Eucharist (this includes discussion points for your community or worship committee), and the video (or PDF) of my talk “Some thoughts on Liturgy“.

*****

If you appreciated this post, there are different ways to keep in touch with the community around this website: like the facebook page, follow twitter, use the RSS feed,…

Kia ora Bosco.

Thanks for your post. My understanding and experience is that liturgical conventions are part of engaging in story telling. The non-verbals are like the props and actions in a play. If they are changed intentionally and well, they can challenge us, deepen our understanding, and help us find new depth to the story.

When used without understanding, they have the potential to confuse, to misinform and to hurt.

They are powerful.

Yes, Mike, this is exactly what I mean. Blessings.

Puts me in mind of the following from Chesterton:

“IN the matter of reforming things, as distinct from deforming them, there is one plain and simple principle; a principle which will probably

be called a paradox. There exists in such a case a certain institution or law; let us say for the sake of simplicity, a fence or gate erected

across a road. The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, “I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away.” To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: “If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.”

“This paradox rests on the most elementary common sense. The gate or fence did not grow there. It was not set up by somnambulists

who built it in their sleep. It is highly improbable that it was put there by escaped lunatics who were for some reason loose in the street. Some person had some reason for thinking it would be a good thing for somebody. And until we know what the reason was, we really cannot judge whether the reason was reasonable. It is extremely probable that we have overlooked some whole aspect of the question, if something set up by human beings like ourselves seems to be entirely meaningless and mysterious. There are reformers who get over this difficulty by assuming that all their fathers were fools; but if that be so, we can only say that folly appears to be a hereditary disease. But the truth is that nobody has any business to destroy a social institution until he has really seen it as an historical institution. If he knows how it arose, and what purposes it was supposed to serve,he may really be able to say that they were bad purposes, or that they have since become bad purposes, or that they are purposes

which are no longer served. But if he simply stares at the thing as a senseless monstrosity that has somehow sprung up in his path, it is he and not the traditionalist who is suffering from an illusion.”

Thanks, Rick. Chesterton has wonderful writing. Blessings.