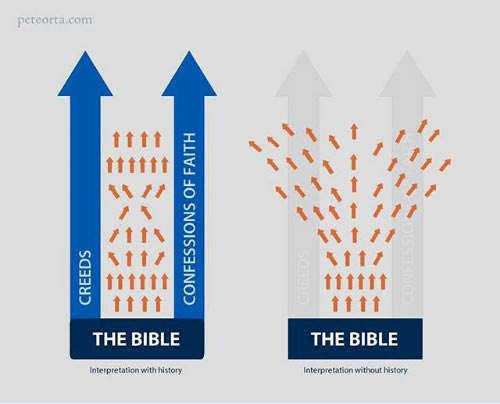

The above picture has been doing the internet rounds as a way to somehow attempt to save those who follow sola-scriptura (the “Bible alone”) from its inherent tendency to individualism and, concomitantly, incessant fragmentation. Serious analysis of the rate of sola-scriptura fragmentation shows the rapid approach of the time when the rate of fragmentation of such communities will exceed the rate of Christian numerical growth!

At the time of the Protestant equivalent of canonisation at the death of Billy Graham, some others are highlighting how (t)his individualistic, Bible-alone approach led to ignoring of social and environmental reform and a political approach that inevitably resulted in the election of Donald Trump and the triumph of the approach of that end of the spectrum. [See, for example, here and here].

There is a common refrain that “sola” does not mean “solo” – but generally that is from those who are convinced that they alone are the sole correct interpreters of “Bible alone” (I hope you saw what I did there!).

Certainly, one can discern a different nuance to “Bible alone” on one side of the (Atlantic) ditch to the other. But, no matter.

The image that “tradition” (including creeds and confessions) is somehow simply derived from the Bible and thereafter stems the dispersion of Christian understanding, retaining it in some sort of acceptable bandwidth is philosophically, historically, and contemporarily unsustainable with honesty.

And if “sola scriptura” means that all tradition (including creeds and confessions) is ultimately subject to the interpretation of the scriptures, then there is, in effect, no real difference, ultimately, between sola and solo scriptura – and no assurance that the arrows on the left (in the picture above) are not doing exactly the same as those on the right.

The fantasy that the tradition from Jesus was passed on until it was written up, and only until it was written up in the New Testament, and that from the moment of the production of that collection of 27 scrolls, suddenly tradition (including creeds and confessions) became a reflection only upon what was contained in those 27 scrolls, is precisely that: pure fantasy.

Yes, clearly, the tradition fed into the production of those 27 scrolls. But, just as clearly, that tradition didn’t cease just because the 27 scrolls had been completed! In fact, some things were simply not written into those 27 scrolls precisely because the tradition continued so strongly and no one thought there was a need to write those strong traditions into those 27 scrolls!

The manner of baptising and the manner of praying to consecrate the bread and wine at communion spring immediately to mind. The sola/solo scriptura crowd will press that because it is not clarified in those 27 scrolls therefore it is less important – “second” and “third-order doctrines” some of them call it. I can just imagine early-church Christians balking at such a suggestion. Quite the opposite could/would be true – precisely because of the presumption that this is how one does things, no one bothered to write it down in those 27 scrolls!

And so I’m sure many of us have sat through sola/solo-scriptura communion services where reading 1 Cor 11:23b-25 somehow magically consecrates the bread and wine. Such an action would certainly have been unthinkable in the early church.

Yes – as with everything – aberrations crept into liturgy, but its reform and renewal wasn’t achieved, wouldn’t have been able to be achieved, simply by reference to the Bible alone; nor to some sort of (early) reflections on the Bible alone. We accessed the tradition through early liturgical writings. The ecumenical, international, and scholarly consensus on the shape of the Eucharistic Prayer derives from the study of early (extra-biblical) liturgy.

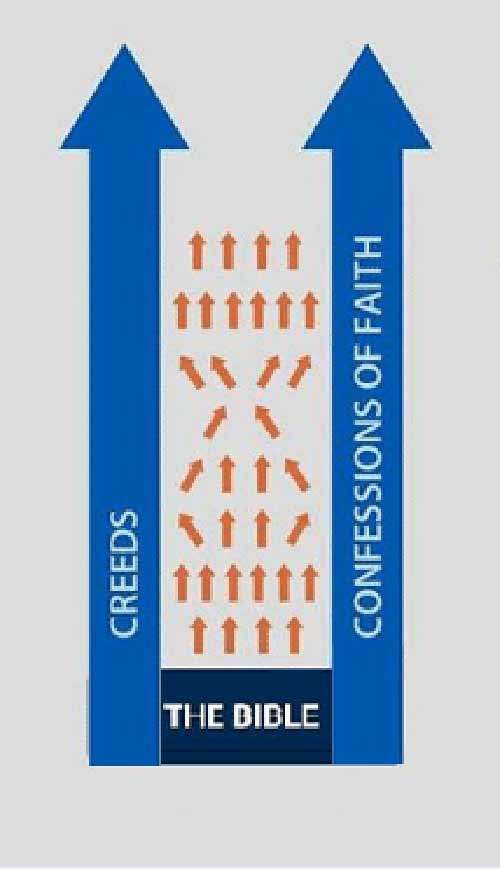

A more sensible picture would be:

The Bible was composed within the tradition. It is recognised as having its authority within that tradition. It continues within the life of that ongoing tradition. Certainly, tradition cannot develop in conflict with the thrust and trajectory of the scriptures – that would mean tradition was veering away.

If you appreciated this post, do remember to like the liturgy facebook page, use the RSS feed, and signing up for a not-very-often email, …

Well, this piece is a muddled mess.

Thanks, CJ. Maybe you could add your perspective to clarify things. Or ask a question where you are finding a point could be clarified. Blessings.

Hey Bosco, who was it that first popularly articulated the idea of sola biblica?

I will put this question out on twitter [we normally use Christian names here CJ]. Blessings.

Your picture brings to my mind containment.

A few years back I attended a church service at a Catholic church in Sydney Australia, where I was refused commune. The presiding priest refused to give me bread as he said I didn’t give the right

response. Three times he asked and three times I said amen. At this stage, I had to move on as there were at least 50 people behind me in the line! After the service, I approached the priest and asked why he did this. I explained that I had been baptised, had my holy commune and confirmation certificates in the Catholic church! He said he was sorry as he had thought I was a tourist? I now carry these certificates with my passport and if I ever enter a mass service in the Catholic church overseas again, I will present them at the church office and ask to be escorted into the church, please. So is tradition important? Do I need to resit these certificates to worship in the Anglican Chruch that I attend? No I’m told these warrants are expectable and maybe a bit of money… Soooo Long Sola. Blessing Ruth

Thanks, Ruth. What a shocking story. I cannot imagine what possible response the RC priest was looking for. Certainly, in NZ Anglicanism, those who are baptised – whatever their age or denomination – are welcome, indeed encouraged, to receive communion. Blessings.

Greetings, Bosco.

One of your best, I believe.

“But there are many other things that Jesus did; if every one of them were written down, I suppose that the world itself could not contain the books that would be written” (John 21:25).

The same can be said of his teaching his apostles, and even more, about the Holy Spirit guiding the development of the tradition underlying and reflected in the Scriptures without being carved in stone. And this isn’t to say, well,anything goes. It is to say there must be both a grounding in the tradition and a shared sense in the church (if not a unanimity) that teaching and praxis are headed in the right direction.

Peace

Thanks, Jay. You seem to me to be helpfully expanding on my suggestion that tradition cannot develop in conflict with the thrust and trajectory of the scriptures – that would mean tradition was veering away. Blessings.

As ever, Bosco, I have mentally indexed your thoughts to mull over them.

Thanks, Trevor. If your mulling leads to interesting thoughts – do bring them back here. Blessings.

Thank you for this, Bosco.

I’ve not heard of ‘solo scriptura’ before. Am I overthinking it if I’m thinking about Latin datives?

Whereas ’27 scrolls’ is a nice turn of anaphora, the manner of folding letters, rather than the rolling of books, became normative for all Christian writings.

Thanks, Gareth. Solo scriptura is sometimes called nuda scriptura. We must move in quite different circles One might have a fascinating reflection how Christianity might be different if binding documents together into a codex had not been invented. Blessings.

Thanks, Bosco, ‘nuda scriptura’ makes better sense: authority based on the bare text of scripture with all context and history stripped away but what the individual reader wants to read into it.

The difficulty I have with the critical pathway you take here, Bosco, is that you take no trouble to speak about the ways in which Scripture is or should be authoritative for Christians, and, as a licensed Anglican priest, for Anglicans in particular.

It is easy to set up “sola/solo/nuda Scriptura” in a way which looks foolish and silly in the light of the reality that the way we Christians decide things is complex and in the light of the reality that how we interpret Scripture has many subtleties – at least as many as there are denominations!

But there are other ways in which Scripture, with or without another word in front of it, is powerful and significant in its authority for the life of the church. There would be no Reformation and no Church of England to which you and I and others reading here are heirs without the reading of Scripture against anomalies in the then church of Europe, anomalies whose claimed authority rested on invocation of tradition – the tradition, for instance, which asserted that the Bishop of Rome was supreme authority over the church, even those kings and queens who belonged to it.

In that same Reformation was a discovery vital for Anglicans and others that, “Holy Scripture containeth all things necessary to salvation: so that whatsoever is not read therein, nor may be proved thereby, is not to be required of any man, that it should not be believed as an article of Faith, or be thought requisite or necessary for salvation.” (Article 6 of the 39A).

This form of sola scriptura is required of you, as a licensed priest, to be accepted as part of the determination of our understanding of “the Doctrine and Sacraments of Christ” here in the NZ Anglican church.

Thanks, Peter.

I think you unfair and incorrect in your suggestion that I “take no trouble to speak about the ways in which Scripture is or should be authoritative for Christians”. I am clear, even in this post, that scripture works within the tradition – and my revision of the diagram illustrates my point.

You appear to function in an either/or approach: either one accepts “sola/solo/nuda Scriptura” or one does not regard the scriptures as authoritative at all.

So, firstly – I reject your assertion that I “take no trouble to speak about the ways in which Scripture is or should be authoritative for Christians”; I do so within this very post. And, secondly, there is also plenty on this website, beyond this post, where I take great “trouble to speak about ways in which Scripture is or should be authoritative for Christians”.

We could become distracted by the particular status in our Church of individual articles in the 39 Articles of Religion. But quoting a particular one “nuda” as if that settles it, I suggest, is not a way forward.

As to my ordination vows, to the question asked at my ordination, “Do you believe that the Bible contains all that is essential for our salvation, and reveals God’s living word in Jesus Christ?” I continue to affirm, without hesitation, “Yes, I do. God give me understanding in studying the Scriptures. May they reveal to me the mind and heart of Christ, and shape my ministry.”

If that is how you understand “This form of sola scriptura”, all you are doing is reinforcing that “sola scriptura” is a term so individually interpreted as to be even more unusable than I suggest in my post.

Blessings.

Hi Bosco

I may have been unfair but I am responding to this post and to its observable tendency to, not to put too fine a point on it, belittle those who subscribe to a sola/solo/nuda scriptura perspective.

Further, in the course of connecting scripture to tradition, your phrasing places Scripture in the tradition and offers no particular sign that I can see that Scripture is invested with authority over tradition – the authority that Christians in the Reformation claimed and proclaimed over tradition gone quite wrong.

Thus when you write in your original post about Scripture and authority, the most you can say about the authority of Scripture is this: “[Scripture] is recognised as having its authority within that tradition. It continues within the life of that ongoing tradition. Certainly, tradition cannot develop in conflict with the thrust and trajectory of the scriptures – that would mean tradition was veering away.”

I do not see where this statement acknowledges any authority of Scripture over tradition. I read it as implying scripture only has the authority of tradition and has no authority in its own right.

I also find your “certainly” quite odd given the ways in which “tradition” has developed “in conflict with the thrust and trajectory of the scriptures” (there are aspects of Mariology, for instance, which are claimed as developments within the Christian tradition but which are deeply objected to by many Protestant Christians as precisely in conflict with the thrust etc of the scriptures; there are aspects of papal power which are objected to by both Protestants and Orthodox.

But the real test of what you claim, I suggest, is whether your view in, say, 1517 in Western Europe would support or suppress Luther’s insights into the role of Scripture in the proclamation of the truth about salvation. I fear it would suppress those insights.

On the other hand, your continuing commitment to studying the Scriptures because they contain all that is essential for our salvation would support Lutheranism. And at that point I suggest you are subscribing not to some quirky or “individually interpreted” view of sola scriptura but, in fact, to the mainstream Reformation view that it is through Scripture alone that we find all that is essential for salvation. In this you are truly Anglican. Again, an Anglican view of sola Scriptura is not some quirk among other views but is aligned with the mainstream of the Reformation.

Thanks, Peter.

Yes, it is the Christian tradition that these 27 scrolls (and only these 27 scrolls) have authority as our inspired New Testament. Without that tradition, anachronistic misreadings of Revelation 22:18-19 as referring to the 66 books bound together as the Protestant Bible notwithstanding, I do not know how you can ascertain what has authority and what hasn’t. So, yes, scripture has authority within the tradition.

In order to play your “let’s imagine we are in Luther’s time” game, might you tell me which of the sola-scriptura interpretations you go with and why: Lutheranism, Zwinglianism, Anabaptists,…? Each of these were also “deeply objected to by many Protestant Christians as precisely in conflict with the thrust etc of the scriptures” – often to the point of persecution, torture, and execution (in their understanding, required by their sola-scriptura reading of the scriptures).

Blessings.

Hi Bosco

Fascinatingly, all major churches are agreed was to what the New Testament is, which is not the situation with the Old Testament. One implication of this is a thread within the tradition/Scripture/authority debate which argues that the church accepting the canon of the New Testament was accepting that which impressed itself on the church as the scriptures of the new covenant as much as the church was determining which writings would be in that new canon.

It is no game to work on what was the high road to the reformed-and-catholic faith of the Church of England from the Reformation onwards in respect of Scripture: the 39A re Scripture are soundly influenced by Lutheranism, and in other matters eschew Anabaptism, modify Calvinism and refuse to go the whole Zwinglian hog. That is, the question here is not about me as an individual and what I think is “sola Scriptura” but about the collective character of the faith we share as Anglicans.

A collective faith, incidentally, which has some width to include evangelicals who want to emphasise sola Scriptura and catholics who want to emphasise scripture within tradition; and yet may be brought to bear against those evangelicals who offer up modern forms of (say) Zwinglianism and those catholics who (say) pay more attention to papal pronouncements than to the conciliar/synodical decisions of their own church, to say nothing of those broad Anglicans who pay lip service to Scripture, preferring to follow the party line of (say) the Green Party (as in a sermon I heard not that long ago!)

Thanks, Peter.

In your promotion of an Anglican “sola scriptura” which is “soundly influenced by Lutheranism, and in other matters eschews Anabaptism, modifies Calvinism, and refuses to go the whole Zwinglian hog”, you are reinforcing my point.

The Reformed scholar Keith A. Mathison is helpful. In his book The Shape of Sola Scriptura, he contrasts the use by most Protestants of the term “sola scriptura” with

In other words, he is describing the picture I produced at the bottom of my post, not the one you advocate at the top.

In practice, I think you and I have heard each other preach enough times to know that (at least in from my perspective), you and I focus on the Bible primarily in our preaching (so I know your last sentence does not refer to me 🙂 ), and do so in a quite similar manner.

Blessings.

I’m not Biblical scholar, so perhaps I’m off topic (or just grossly misinformed). But when I read the words “Sola Scriptura” in the title, I thought of Luther, of course. Then, however, I thought of the peculiar version of this idea (I’m tempted to say perversion, but I’m not supposed to be judgmental) used by Southern, White, American, Protestant Evangelicals. They claim that the Bible is sufficient in and of itself, and any fool can read and understand fully the plain meaning of the text if only he has adequate faith. Something like that. But then, they go on to insist that if the reading fool comes up with views that differ from those of the disciples of Al Molher, Jerry Falwell, etc., then the fool has read it wrongly, and obviously is lacking in faith. Something like that. Please set me straight if I got this all wrong.

But my problem, as a fool who has read the Bible off and on, is that it seems to me there are things we can’t possibly understand unless we delve deeply into ancient languages and cultural understandings. My problem of the moment is with Samaritans. Somewhere along the way, I got the vague impression that a Samaritan was some kind of heretic foreigner, probably unclean and/or disease ridden, and probably devious and not to be trusted. Perhaps something like the views of gypsies some 100 years ago (or the Yellow Peril!), likely even worse. But I have the feeling that these days most of us just think Samaritans are merely people from another town or state, perhaps the other side of the tracks. Yeah, a bit different, but not really so much.

I never hear anyone talking about the Samaritan woman at the well, the one with 5 former husbands and a current live-in boyfriend who was not a husband, in those terms. Yes, she had a bit of a randy lifestyle, but I have a vague feeling that her lifestyle was the least of her problems for the 1st-century Jews. But we never address that, so miss a major facet of the story.

So, my question is, how are normal people supposed to understand scripture when there is a whole back story, something self-evident to Jews 2000 years ago, about which we have no clues today unless we’re to steep ourselves in ancient scholarship? Yes, this is where tradition might come in, but is seems in our “tradition” these days to ignore such important back stories.

Thanks, Larry,

Some of what you write is an expansion upon my point that the term “sola scriptura” often, on the other side of the Atlantic, is the term used for what, in the European/Continental understanding of many, would be called “solo -” or “nuda scriptura”.

Agility in biblical languages and culture is, as you indicate, essential. I indicated that in my recent post on our debate on Saturday about committed same-sex couples. Taking a verse out of its contexts and in translation, without accepting that there are other scholarly ways of understanding such a text, is frought.

The Samaritan woman at the well story is a good example. Even your mentioning of “1st-century Jews” appears anachronistic – a mistranslation I suggest.

I’m not at all sure that “she had a bit of a randy lifestyle”, but one could add to that the point that she didn’t go to the well when the other women at the village did. This woman appears despised by her village, which was despised by Judeans, whose ancestors had been humilated by Babylonians – the history of which led to the despising. All this would have been obvious to the first hearers of John’s story.

Blessings.

Thank you for noting the “canonization” of Billy Graham and including the links. I have been shocked, in not a good way, at the elevation of Rev. Graham as a near saint and the laying in honor in our Capitol. This grates at me both from a religious concern and from an American concern (with our alleged separation of Church and State). This action is a clear pandering to the evangelicals here who are quite willing to overlook any sin as long as they get their vote on our Courts. (His son Franklin’s hypocrisy in defending Trump’s infidelities is just one recent example–“Hey Franklin, ignore the payoff of the porn star and we’ll make a national scene of your father’s death. The Capitol, no less!! First religious person given this honor! Think of the donations that will come in!”) They can always find justification in the Bible for their desired action. The “indulgences” of our time, I feel.

My head reels a bit with all the sola/nuda… but I appreciate how your writing (and some of the comments) makes me keep going back to chew on the words. Good lunchtime readings. Thanks for this.

Okay, I’m a Lutheran who studied under the modern greats… so I’m soaked to marrow in reformation theology.

Sola Scriptura is not a rejection of true tradition at all. It actually defines and embraces tradition. It is an exegetical hermeneutic.

Tradition that does not comport with scripture is eisegesis… it can’t possibly be legitimate tradition.

A sola scriptura hermeneutic leaves mysteries mysterious and forces us to reject tradition that over or under interprets the scriptures.

Here’s an example: The eucharist. Some teach it is only a symbol or rememberance. Others believe the elements become body and blood. Sola Scriptura forces us to leave the mystery intact. The elements do not become anything, and the eucharist is not a rememberance devoid of the real presence… it is a sacrament, a real thing, not a memory of a thing. This IS my body, This IS my blood, … as often as you drink my body and blood, do so in rememberance of me….

The theologies that conflict with sola scriptura are inadequate traditions… because these are theologies that try to explain the pure mysteries… to look behind the veil, to vie with God himself.

Here’s another difference attributed to sola scriptura… which is the reason way true Lutherans of the Reformation… the firstborn of the reformation I must say, reject the historic episcopacy.

Tradition reads into scripture what is not there. The h.e. is eisegetical. Peter was not the first pope of the church. If anybody was, it was James. In fact Peter and Paul were such a mess in the field they were called back to Jerusalem. Peter especially was a lousy pastor… he was all glam and no substance.

Though we can’t really accept tradition on the h.e. , we can be certain that every Christian has been laid hands on somebody who was laid hands on by somebody was was laid hands on by Christ….

Thus the central Reformation principal of direct access to Christ. In sola scriptura, the argument that tradition makes of the church hierarchy… or any number of biblical issues… is not legitimate…

So with sola scriptura, we now distinguish between legitimate, or necessary tradition, and illigitimate tradition.

Tradition that says more or less than the scriptures id illegitimate.

Thanks, Rev. Conner.

I think you are not responding to the central question dealt with in this post – illustrated by the top or bottom pictures (the latter being my one). There are those who see all tradition as deriving solely from reflection on the scriptures (top picture). I do not – I see the scriptures developing within the tradition.

Those who declare themselves to be “sola scriptura” in fact, contrary to your argument, do end up with a position (your example) on the nature of the Eucharist. Martin Luther himself springs to mind!

I’m not sure where, from the Bible, you can trace the chain you describe back to “somebody was was laid hands on by Christ”.

My illustration, of the shape of the Eucharist and of the Eucharistic Prayer, is certainly “tradition that says more than the scriptures” – I would be surprised if many would agree with you that this tradition is “illegitimate”.

Your comment highlights the issues with sola scriptura by someone “soaked to marrow in reformation theology”.

Blessings.

Just a very unacademic, simple comment from me:

Scripture is only important to the extent that it can reveal to ‘the simple’ (as Jesus proclaimed) the heart of Jesus’ message. This Jesus indicated with his prayer; “I bless you Father, Lord of heaven and earth, for revealing these things to the simple, for that is what is has pleased you to do.”

Yes, Scripture is vital to our understanding of God at work in th world through Christ. However, after thr human life span of Jesus, the Holy Spirit – as Jesus said s/he would – has been sent to ‘lead you into all the Truth’. This indicates embarking on a journey – with Scripture as initial guide. BUT, we now, also, have ‘another Comforter’ Who is still at work in God’s world ‘leading us into ALL the Truth’

This is where a Spirit-led hermeneutic is required.

Thanks, Fr Ron. I note that both of your quotes from Jesus are drawn from the scriptures, and I am reading your “initial guide” not as being historically back in the church’s past but the place where we begin each time. I would emphasise, from my own perspective, my final line – “Certainly, tradition cannot develop in conflict with the thrust and trajectory of the scriptures – that would mean tradition was veering away.” I have a couple of further posts in mind that pick up some of these points. Blessings.

Thanks, Bosco.

Your words ‘thrust’ and ‘trajectory’ are important in this discussion – implying a dynamic movement in understanding which is still going on. Deo Gratias!