The frog-boiling metaphor is well known.

The story is that if a frog is put suddenly into boiling water, it will jump out, but if the frog is put in tepid water which is then brought to a boil slowly, it will not perceive the danger and will be cooked to death. The story is often used for the inability or unwillingness of people to react to or be aware of sinister threats that arise gradually rather than suddenly.

I recently had reason to look up the Census statistics of a reasonable-size NZ city:

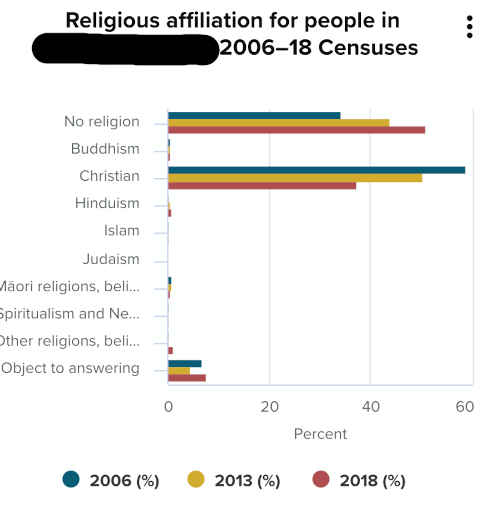

I’m blanking out the city as this is not important – I’m not “picking on” a particular city. What I want to highlight is that across 3 censuses (usually 5 years apart), those who saw themselves as part of no religion grew from just over 30% to just over 40% to just over 50%. Those who saw themselves as Christian dropped from about 60% to about 50% to about 35%. Let me repeat the point: those who declared themselves Christian on the census, in a period of about a decade, dropped to half.

Some church people will come up with various “explanations” (read “excuses”): they were not really Christians in the first place; they are simply being more honest;… The census provides no reasons – all we can say with confidence is that in these stats, in a decade declaring one is a Christian, in the relative safety of a census, has halved; and, concomitantly, declaring one has no religion has nearly doubled.

There are those who think and even proclaim that renewal and church growth is somehow inevitable, that this is part of some sort of cycle. They seem to know no history, unaware of the 600 or so dioceses that existed in North Africa. Once.

When the decline of Christianity is acknowledged, I have seen online, not in this country, the gloating that other denominations are declining four times faster than their one! The hole in the boat is not where I am sitting!

When I visit a Sunday Anglican Church service, it is not unusual for the vast majority of the congregation, if not all, to be older than I am. And the impression I get is that, like the boiling frog story, people take this for granted.

Now for the second part of my heading:

When the guru sat down to worship each evening, the ashram cat would get in the isway and distract the worshipers. So he ordered that the cat be tied during evening worship.

After the guru died the cat continued to be tied during evening worship. And when the cat died, another cat was brought to the ashram so that it could be duly tied during evening worship.

Centuries later learned treatises were written by the guru’s disciples on the religious and liturgical significance of tying up a cat while worship is performed.

From Anthony De Mello, The Song of the Bird

This is not exceptional: I visit a Sunday Anglican Church service in a building which was built for a vigorous parish with a choir and originally with the long, rectangular sideboard-like altar against the far, east wall. During the Eucharist, the priest would have been at that far end with young servers, then a full choir, facing each other in the choir stalls, and then a good, mixed congregation. Some time, over half a century ago, the vicar taught a series on liturgical reform and the altar was pulled out a little from the east wall, enough for the priest to get behind it and face the congregation.

But the choir is gone now. And so are the (young) servers. At the start of the service, the priest leads from half way down this building, with the empty choir stalls behind the priest. But when it comes to Eucharistic Prayer (The Great Thanksgiving), the priest moves through the half of the church building that is empty, between the empty choir stalls, through altar rails, and then this priest stands, way in the distance, alone behind the sideboard – this altar that was pulled out from the wall in the 60s, but nothing else has been done in the intervening years. The priest stands at that distance as if behind a large kitchen bench, like a sole bartender in the distance.

There is no sense whatsoever of a community gathered around a shared table (in circuitu altaris around the altar; in circuitu mensae around the table). Even in church buildings where people have dragged the sideboard-altar between the empty choir stalls and now this rectangular box stands not as something that in any sense everybody unites around, a squarer, family table. Even when many may have found this a radical alteration (“altar-action”!), it continues to appear as an architectural divide, separating the clergy from the lay, the show from the audience. And people just seem not to see these things, because, little by little, the frog was boiled to death; and this is the way we have always, unquestioningly, done these things. The altar has always been that shape. Those choir stalls have always been there. We’ve always used a burse and veil with the burse stood vertically on the altar. Younger people just aren’t interested in church. And so on, and so forth.

I recently read one young person’s faith journey – what this person experienced, in relatively few communities, was a sense of reverence, a sense that what was being done was important. Is that the reality in your community? Or is it a poetry recitation in response to page numbers? A sing-along in response to hymn numbers? The bland leading the bland? A gathering of those who are similar to each other – even gathering in shifts for different tastes, or ages, or theological approaches? Or even differentiating by having different gatherings at the same time in different venues on the same property? The other day I saw a street with 5 different denominational buildings all in view of each other – that is a dead frog that is rarely even noticed – except, maybe, by non-Christians!

How might a community move past the boiling frog and guru’s cat? I suggest, there needs to be increased honesty and objectivity. This includes being clear, humble, and honest about statistics. What about getting some younger, non-Christians to come and look at your church building? At a service? Allow honest questioning; when is this chair ever used? What is the point of this? Why do you do that? If this is too threatening, get some young Christians from a very different denomination in; or at least, what about allowing everyone in the community to try and channel such a viewpoint? Imagine yourself a non-Christian visitor. Go round your building – what do we use this for? Is there a continuing reason for the building to be a storage shed for furniture that will never be used? Video services and critique them. Covid may have gifted some communities that as they livestream and record services.

What do you think?

If you appreciated this post, consider liking the liturgy facebook page, using the RSS feed, and/or signing up for a not-very-often email, …

A helpful and horrifyingly stark picture you’re painting here Fr Bosco. But you’re not wrong. And I fear the 2 years of COVID are only going to hasten the trend. I’m hopeful that some of the redesign of St Mark’s, Opawa is a (small) step toward modernising the architecture of worship, but it’ll depend on how we inhabit and use the space, and which furniture we allow to be dragged back in.

However I’m also aware that there’s a tension here. Some of the external reviews might lead to something akin to the “seeker-sensitive” services of the 90s that might have had their day. I feel like sometimes one can get a better sense of reverence and importance through mystery.

Either way, I’ll continue to wrestle with some of the issues you raise. I’m hopeful that you might work alongside our new Archdeacon for Regeneration and Mission to offer some specific feedback and review of some services. You’ll always be welcome in the back pew with a notepad at our place.

You are right, Ben, to highlight reverence – I made a mention of it in the post. And I look forward to seeing how your renewed, post-quakes worship space looks and works. Blessings.