There are different ways to be a community, a Christian community [or any religious community].

You could focus around a leader. You could find unity by all signing up to the same list of beliefs. You could find unity by a common mission drive. You could focus on knowing each other and being like a large caring family.

There is often a mixture of these sorts of sources of unity in churches. But Anglicanism, as well as having elements of all these sources of unity, has a particular tradition of common prayer as a significant source of unity.

The maxim, Lex Orandi, Lex Credendi (as we worship, so we believe) is a saying particularly appropriate within inherited Anglicanism. We could expand the saying further, as it often is: Lex Orandi, Lex Credendi, Lex Vivendi (as we worship, so we believe, so we live).

The model that is at work here is one of relationship. Prayer, worship, is about relationship – relationship with God, our relationship in Christ with God. We are drawn into Christ and so, together, are in the relationship with God which we call prayer, worship. And, in and through that, we are in relationship with one another. That is the purpose of common prayer, common worship. That is the end of common worship.

The discussion that this post is focusing on is also the other meaning of the word “end” – finishing. This particular post comes in response to a number of discussions around how to go forward from The Episcopal Church’s 1979 Book of Common Prayer.

I serve in a church (The Anglican Church in Aotearoa, New Zealand and Polynesia) where our Prayer Book is a decade younger than that 1979 book. We are also significantly smaller than The Episcopal Church. And we are a church that has, step by step, abandoned common prayer. Our church is held together by the smallness of our size – and when I say “held together”, it is doing so currently only by the skin of its teeth with a last-ditch attempt by many to stress a list of doctrines to hold to, often drawn from the very common prayer that has been abandoned, and particularly discarded by those who now want to mine it for the list of doctrines that they want everyone to tick every box of.

If TEC wants to see the results of abandoning common prayer, let them send some people over to see the Anglican Church of Or.

My intention is to have other posts following this one that will pick up the dialogue happening around the value or not of common prayer. As just one consequence – how much reflection has been done around the loss of time, money, and energy to create unrelenting novelty in community after community where congregations are, numerically, not much different to an average school class size? Have we become a shrinking club of novelty-idolising Baby Boomers living off our inherited funds and properties as we entertain ourselves into historical oblivion?

Here are some of the online articles that this post begins to dialogue with: here, here, here, here, here, here.

Here are some previous discussions, on this site, around the loss of common prayer in

ordination

baptism

marriage

eucharist

If you appreciated this post, do remember to like the liturgy facebook page, use the RSS feed, and sign up for a not-very-often email, …

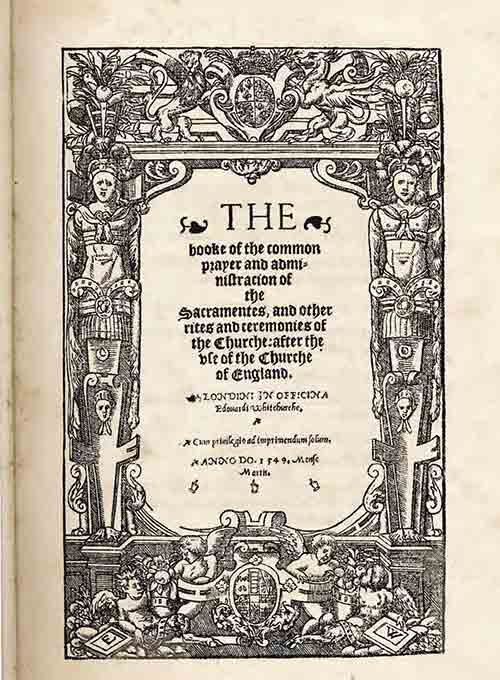

image: 1549 Book of Common Prayer

There was a time when we Anglicans all read from fairly similar Prayer Books. No matter what your doctrinal emphases, public prayer happened the same way. One meaning of the ‘common’ in ‘common prayer’ is that it is public, as opposed to private prayer. The push by later Tractarians and ‘Ritualists’ to bend the Prayer Book to their liking is the beginning of actual diversity in common prayer, or divergence from it. Today the push seems to come from charismatic evangelicals and social liberals who urge for more ‘freedom’. I think there are some good arguments for increased freedom (in mission and outreach), but we’ve seen plenty of negatives. The complexity of our liturgical provisions are a result of this search for freedom. So now we have clergy wanting to be free of liturgical restraint because they can’t work out how to make it work.

Looking at my bookcase, I have An Australian Prayer Book, A Prayer Book for Australia, and A New Zealand Prayer Book He Karakia Mihinare o Aotearoa all lined up together. Does it start going wrong with the indefinite article?

Thanks, Gareth.

I think that your point about Anglican catholics being congregational – and in your analysis being the beginning of Anglican liturgical congregationalism – is one of the most significant elephants in the liturgical room. With the advent of A New Zealand Prayer Book He Karakia Mihinare o Aotearoa, there was no need for Anglican catholics to “bend the Prayer Book to their liking”, but here they, in fact, continued to disobey what was agreed to so that a catholic understanding of common prayer was just as lost amongst the “charismatic, evangelicals, and social liberals” who also abandoned our agreements.

Your highlighting of the indefinite article is also important. Within our Prayer Book are different rites for the same liturgical celebration where there is no family resemblance in the wording whatsoever. The only “common” about them is that they are bound between the same covers.

Blessings

Our Archdeaconry is currently having discussion evenings to look at the future of the church. Four of five fulltime priests have retired, are retiring, or are moving on. A new direction is being sought, perhaps combining resources/ministries, having worship styles relevant to today’s people. My own circle of friends use words like disenchanted, disillusioned, despondent. Others see the future as exciting. On the first evening, sitting at tables with folk from each congregation, I asked a young woman what she saw as exciting, for I was having difficulty knowing what to ‘grab hold of’. I think I’m prepared to get excited if I can see that our direction has some purpose and clarity. Her response was “Get rid of all this religiosity”.

Your paragraph beginning “The model that is at work here is one of relationship” sums up what I look for and what is being/has been lost. I was taught that the purpose of my ministry was to provide a safe place for people to encounter God. Last Sunday I attended 8am worship at one of the churches. I felt at peace and came away refreshed. It is probably the only “liturgical” one left in our area. The people are friendly and caring, and property-wise they run a successful operation. A 93 year old said, quite voluntarily as we walked out after the service “I LOVE this church.” Their priest (who was sick last week) is retiring. A retired priest took the service. I wonder what the future will be for them.

I find some nebulous consolation in the thought that the church won’t die out. It never has. It belongs to God. But how far it will ‘go down’ before rising again remains to be seen.

Thank you for all you offer on this site. I feel encouraged, enlightened and enriched (better than those earlier “dis-” words!)

Thanks for your encouragement, Heather. And for your reflection.

I would only add – having travelled extensively through North Africa where the early church was thriving and now is very thin – that, yes, the church won’t die out, but there’s no assurance that it will remain vibrantly in this or any particular country. Nor is there any assurance that the Anglican form of it will continue.

I hope that, as you did, people will be able to continue to find communities where worship is refreshing.

I also wonder whether church in cyberspace may be a place where we can encourage each other in a way that wasn’t available before.

Blessings.

Twenty years ago I can remember juggling BCP, Hymnal, and bulletin and thinking it was a bulky and cumbersome process and not very friendly to the visitor/outsider/uninitiated.

But it’s been many years since I last visited an Episcopal church that actually required the use of a physical copy of the BCP. Usually the necessary parts of it are just interwoven into the bulletin, obviating the need to leaf through the BCP to find just the right words, prayers, etc. This is also happening in many cases with the hymnal.

Thanks, Jonathan. Screens are another way that this is happening here. Blessings.

Interested to see how your responses develop, and grateful to see the interaction, Bosco.

Thanks, Zachary. Nice to have you here (readers may notice your connection to the posts that I’ve pointed to). How did you find this post? If there are further posts on Covenant following this thread (or any that I’ve missed) please can you let us know in a comment here? Blessings.

Thanks, Bosco. I found the post due to an automatic pingback notification: generally, when folks link to our material, I get an e-mail. It doesn’t always work, but it’s useful when it does.

I think you generally caught all the posts that went up at the time, though there have been some more since then. I’d recommend folks simply click on our liturgy “channel” to see most of them conveniently. http://livingchurch.org/covenant/category/liturgy/

We’ll have another piece on liturgy and BCP revision this week.

(And, apologies for the delay in response.)

I wonder if the processes we use in making prayer books is part of the problem. We task a group of liturgists to go away and bring back a book. That group will consist of representatives of various views. They bring their drafts to synod, which is political while pretending it isn’t. And synod members have a cracking at the draft based on misremembered seminary classes and what their training rector used to do. The Anglican Catholics will demand a ‘consecratory’ epiclesis in the ‘right’ position (even if their views would count against the Roman Canon). The Evangelicals will demand a less realist approach and decry the Bendictus and Agnus Dei as songs for the re-immolation of Christ. Some good revisions are made, but there’s much nonsensical bickering over partisan bugbears.

I wonder whether Vatican II was any better. At least it took its time, was authoritative, and based liturgical reform on doctrinal agreement and canon law.

Our canons still seem to presuppose some idyllic past of liturgical usage. If anything is approached with more trepidation than liturgical reform, it’s reforming canon law, and both are seen as distractions from mission. I think this doesn’t help. I’d like to see canons that set out clearly the norms and boundaries of liturgical use. I’d like to see clarification of the limits of ius liturgicam of bishops. I’d like to see bishops having some kind of ‘liturgy order’ through which they can grant parishes and chaplaincies certain exemptions. This would mean that bishops have to stop turning a blind eye to divergent uses, and enter conversation with those that want to do things differently. We’re doing things the wrong way round if synod votes that Communion need not be celebrated every Sunday, nor the offices prayed every day, nor a surplice be worn. Synod should insist on these and then let bishops issue exceptions on a case-by-case basis. If a pastor wants to preside in a suit and tie or jeans and t-shirt, she will have to present a case for it to her bishop. I wonder whether canons are part of the problem, when they hark back to a day when one book with one way of doing things was the order and deviation was punished. It’s no wonder bishops and their clergy avoid talk of what is legal.

Thanks, Gareth,

Much of what you say applies in different ways here in NZ. But a lot of it does not – which may make NZ Anglicanism an important reference for other provinces wanting to go in this direction:

In the very many eucharistic prayers authorised in our province, not a single one has “a ‘consecratory’ epiclesis in the ‘right’ position”. We are, however, allowed to use any eucharistic prayer authorised anywhere in the Anglican Communion. We have our own framework for writing them and, of course, are allowed to use the frameworks authorised elsewhere. Even with this, clergy will produce their own eucharistic prayers possibly following ‘misremembered seminary classes’ but the majority of these, having no seminary formation, will make up what feels right, and what, you and I would realise, is not a eucharistic prayer at all. I am not in favour of a liturgical-police approach, but any mention to bishops normally leads nowhere. In fact, bishops fall into similar patterns to what is described of other clergy.

Although bishops have acted as if they have ius liturgicum, until this year’s change to our Constitution, they never did. In the context of our liturgical mess, I advocated strongly (on this site) against changing the Constitution and narrowly lost.

We have no systematic body of canons. Our canons are a collection that has grown like topsy in response to specific issues and can even be in conflict with doctrine which also is labyrinthine to attempt to navigate.

Communion need not be celebrated every Sunday – so if you are a Christian living somewhere with only one Anglican church in your region it is pure luck whether you can receive communion on Sunday if you seek to. The daily office as a requirement was abandoned decades ago.

The links at the bottom of my post begin to explore some of these points further – the loss of common prayer in…

Blessings.

May I suggest, Bosco, that a part of the problem is the people’s lack of teaching about the eucharist – at the heart of our Anglican worship. When liturgy is replaced by Praise services – sans Eucharist – the congregation neglects to user the most precious of our resourcves for public worship.

There are still some of us in the Anglican Church in Aotearoa/New Zealand who believe the celebration of the Eucharist to be both source and focus of our mission – to the extent that Daily Eucharist is still at the heart of what we do,

I cannot understand the movement towards the less frequently celebrated Sunday Eucharist movement. Who and What is it that is at the centre of such a cult of deprivation of the only tanglible sign of God’s Presence among God’s gather community if Christ is not frequently welcomed in the forms he indicated – of Bread and Wine at the Eucharist?

Thanks, Fr Ron. Yes – Eucharist and the Daily Office were certainly the heart of common prayer. Blessings.

If nothing else, Bosco, your honest reportage about your province’s liturgical struggles helps me keep a healthy perspective. There are far worse things than the leaden mediocrity that unites my own province. I should count my blessings more realistically.